By Paul A. Djupe, Denison University

[image credit: CNN]

The Southern Baptist Convention met last week, which explains why we are focused on the social views of evangelicals (Ryan Burge just wrote for RNS on support for women in the pulpit). The specific controversy here was generated by prominent social media religious figure Beth Moore who gently criticized the SBC’s tight lid on women in authority roles, suggesting that there is a “generous orthodoxy” in the churches where she worships and leads. That orthodoxy is “complementarianism,” which means that men and women were created by god to have different, but complementary roles. Those roles for women do not, in their view, include preaching: “For a woman to teach and preach to adult men is to defy God’s Word and God’s design,” wrote Professor Owen Strachan at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary. Reinforcing that notion, the SBC also resolved to continue their opposition to including women in the selective service military draft, “Requiring women to register for the Selective Service alongside men would be to treat men and women interchangeably and to deny male and female differences clearly revealed in Scripture and in nature.”

That’s a strident view that has to have spill-over effects to the rest of the social world. One could easily imagine that such a religious view would also inhibit support for a woman in really any leadership role – in the workplace, university, organization, family, or government – or for women seeking equality. So, this spat raises the larger question about the distribution of sexist views among religious groups. Personally, I’ve been looking for an excuse to look at the Voter Study Group sexism measures. Fortunately, they also have reasonable religion measures (at least the born-again identity to help parse Protestants in 2018).

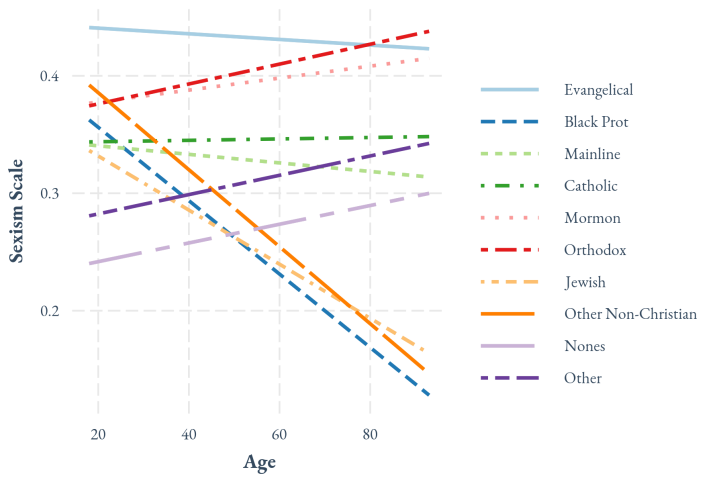

The figure below shows how members of religious traditions stand on 6 measures of modern sexism. They include an explicit call for women to return to traditional (read: “complementary”) gender roles, reject that women face special problems, suggest that seeking equality is a problem in and of itself, and disagree that equality yields benefits to society. (Quick note: the scale in the survey runs from strongly agree to strongly disagree, which I’ve collapsed to run from 0-1; I’ve recoded the scale so that a higher response is considered the more sexist one, in favor of more traditional roles, etc.).

White evangelicals are always near the top of the list, holding the most sexist attitudes. Often indistinguishable from Orthodox and Mormon adherents, more evangelicals wish women would return to traditional roles, suggest that women seeking equality are looking for “special favors,” deny women lose out on job offers because of discrimination, think women complaining about harassment are causing problems, deny that sexual harassment is still a problem, and have weaker commitment that gender equality has brought benefits. So, yes, evangelicals, of which the SBC is apart, are more likely to adopt attitudes at odds with women’s equality.

To be fair, though, most of the US is not wholly sexist according to these measures and neither are evangelicals. The group averages tend to lean to the low side of 0.5 (meaning they, on average, chose less sexist responses on these questions). White evangelicals are more sexist than most groups, but only on “special favors” and “discrimination costing women jobs” are evangelicals on balance adopting sexist attitudes; they are also close to a majority on the item that women cause more problems than they solve by complaining about sexual harassment, which is interesting given the reporting about sexual abuse in SBC churches.

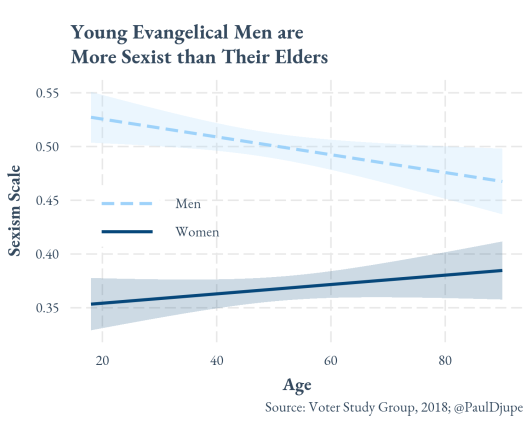

I couldn’t help but wonder whether there is a gender gap on these items. It would make sense to find one and be especially problematic in patriarchal religious groups in which men still make and enforce policy. This time, I added up the responses to all six items (again so that the high responses were the more sexist) and the results are clear. White evangelical men are, on balance, sexist and have the highest average score among any other gender-religion group. Given their power in their denominations and congregations, we can expect that white evangelicalism will continue to resist gender equality projects in their own organizations and in society.

What’s notable, of course, is that there are gender gaps in sexist attitudes in almost every religious group (d=difference). The biggest gap is actually among a liberal group – Jews. The second largest is in a set of denominations that has ordained women pastors for decades – mainline Protestants. Mainline women are quite liberal on these matters, though mainline men are near the most sexist; they’re in third place, just ahead of Mormon men. Speaking of Mormons, there is no gender gap among them. I think this is not surprising given the cohesiveness of the group. Nones express some of the least sexist attitudes, but there is still a gender gap that is not much different in size than any other group’s. Perhaps the attachment to a religious institution can help explain the average sexism, but even so we should expect that men will still take more status-affirming positions on the drive for gender equality.

Is this going to change in the future with generational replacement? It is certainly conventional wisdom that young people are less sexist than older people. A lot has changed in the past 50 years at the beginning of the women’s movement and society appears to be more open to women’s equal place. However, most religious groups do not vary much in their sexism by age (see figure below). Mainline, evangelical, Catholic, Mormon, and Orthodox adherents show no significant movement across the full age range. The rest do, but in different directions. Young nones are less sexist, as expected, though young Black Protestants are more sexist. They are joined in their higher sexism levels by younger Jews, and other non-Christians (Buddhists, Hindus, and Muslims – their samples are too small to break out). But realize that these older folks were alive and active during the civil rights era and perhaps their distinctiveness makes sense – religious minorities were on the front lines of those fights. Altogether, there is no simple story here about how members of religious organizations will treat women in the future, though again all religious groups save 1 are on the less sexist side of the scale.

But what about evangelicals? They were the inspiration for this piece given the SBC meeting, so let’s take a closer look. This breaks out the age trends by gender and they are revealing. Young evangelical men are more sexist than their granddads. Young women are slightly less sexist, but not significantly so. So the null result above gains some context – it would be significant were it just to include men.

Why are the results from young religious adherents so different from what we might expect? We need to remember that many people are leaving churches and then leaving their religious identification altogether. The rate of growth of the nones is highest among young people, but is not isolated to youth. And the driving force of apostasy is disagreement and difference, so that disagreement over Trump drove out some evangelicals, disagreement over LGBT issues drove away others (PRRI found), and so on. Some conservatives leave liberal churches and some liberals leave conservative churches, though clearly there is more of the latter since there are more conservative churches.

Then turn this around and ask, who stays? Those who agree with the church status quo, which would be those who are more traditional, more conservative. Yes of course there are young members who are dedicated to turning their religious group in a different direction, but they are not the majority. Young evangelicals are just as Republican as their grandparents, though there are issue exceptions like the environment. So, if you thought that a new generation of evangelicals is likely to come of age and chart another course, that seems mistaken from the point of view of these data.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (see his list of posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

[…] Djupe has some interesting numbers in a blog post at Religion in Public: Support for Women’s Equality Across Religious Groups Varies Considerably. Read his analysis there. Below are some of his […]

LikeLike

[…] roles for women to play in public life. A few weeks ago, I wrote up a description of how different religious groups stand on women in public life. Generally speaking, I found gender gaps within each religious tradition and higher degrees of […]

LikeLike

[…] perfect sense. Evangelical churches, in particular, advocate for the maintenance of traditional “separate spheres” roles, with men responsible for public life and leadership, and women for home and family. On […]

LikeLike