Samuel L. Perry and Andrew L. Whitehead

In the past few years, and particularly in the past 6 months, “Christian nationalism” has become a bit of a buzzword. Recent op-eds describing and decrying (or in rarer cases defending) it have included the good, the bad, and the breathtakingly idiotic. A number of important articles have cited various findings from the burgeoning research on Christian nationalism. However, as we stand less than 10 months away from the 2020 Presidential election, there is an urgent need for synthesis.

After five years of empirical research, culminating in our forthcoming book, we believe the pieces combine to tell a larger and significantly more sinister story.

Simply put, Christian nationalism—an ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of Christianity* with American civic belonging and participation—is a form of nascent or proto-fascism. Not full-blown fascism (yet), but a complex of ostensibly-religious ideologies, identities, and values that could potentially lead toward fascism given the right recipe of resources, political opportunities, and a population acclimated to its underlying ideals.

Don’t miss the asterisk. It denotes that the “Christian” content of Christian nationalism stands for something far beyond (and we believe altogether different from) mere orthodoxy. “Christian” in this sense represents more of an ethno-cultural and political identity that denotes a specific constellation of religious affiliation (evangelical Protestant), cultural values (conservative), race (white), and nationality (American-born citizen).

It is this subliminal, unrecognized content of the word “Christian” that gives Christian nationalism its fascist potential. Yet even in nascent form, the tell-tale characteristics are unmistakable. Consider the common features of fascist societies outlined by Yale Philosopher Jason Stanley in his recent book How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them. Characteristics include:

- An ideology built on reference to a mythic past.

- Populist support for strongman demagogues.

- A culture of anti-intellectualism, including anti-education and anti-science beliefs.

- An ideology that views social hierarchies as normal and necessary.

- Idealization of patriarchal families.

- Peace maintained by authoritarian “law & order” tactics.

- Strongly pro-nativist/anti-pluralism.

- Foments cultural anxiety about sexual deviance.

- Pervasive victim mentality.

Reading Stanley’s description of fascist societies, we are struck by how our collective empirical snapshots of Christian nationalism combine to make one chilling mosaic.

- Christian nationalism is built on an interpretation of history that connects America’s founding and future success with its Christian heritage (reference to a mythic past).

Christian nationalist ideology is also among the strongest predictors that Americans…

- voted for Donald Trump in 2016 (strongman demagogue).

- oppose scientists and science education in public schools in favor of creationism (anti-education/anti-science).

- hold prejudiced views against racial minorities and show relative favor toward white racists (supports social hierarchies).

- hold traditionalist gender attitudes that envision women in the home and men leading at work and in politics (idealization of patriarchal families).

- hold views supporting capital punishment and the police “cracking down on troublemakers,” and even justifying police violence against African Americans (maintaining authoritarian law & order).

- hold anti-immigration views, expressing strong suspicion toward Hispanic immigrants and Muslims (strongly pro-nativist/anti-pluralism).

- hold views in opposition to same-sex marriage or civil unions and, as we show in our book, transgender rights (foments cultural anxiety about sexual deviance).

And while we have not quantitatively studied how Christian nationalist ideology is related to a “victim mentality” characteristic of fascist regimes, such a mentality is constantly on display among America’s most prominent Christian nationalist thought-leaders like Robert Jeffress, Franklin Graham, Mike Huckabee, Michelle Bachmann, or Tony Perkins.

Recognizing Christian nationalism as proto-fascism also helps us to disentangle it from religion itself.

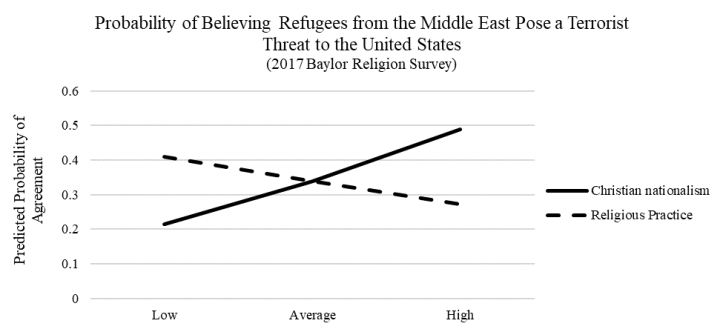

Our research clearly demonstrates that Christian nationalism actually has little to do with religiousness per se. In fact, when we compare how Christian nationalist ideology and traditional measures of religious commitment (e.g., worship attendance, prayer, sacred text reading) influence Americans’ political attitudes and behaviors, we find they work in the exact opposite direction.

Consider Christian nationalism and Americans’ views regarding refugees from the Middle East. The more someone affirms Christian nationalism the more likely they are to believe such refugees pose a terrorist threat to the United States. However, as the chart shows, the more faithfully someone practices their religious faith, the less likely they are to hold such xenophobic and Islamophobic views. In fact, we see this countervailing trend between Christian nationalism and religious commitment for just about every attitude we measure―where Christian nationalism zigs, religiousness zags.

Why does Christian nationalism behave so differently from traditional religious commitment? Because it is a religion of white conservative America that worships power. It is “Christian” in name, but only as a code of sorts. Much like labels such as “terrorists,” “welfare queens,” “illegals,” and “criminals” become racially-coded dog whistle terms in our political discourse, so has the term “Christian” in the minds of many conservative Americans. It stands for “good and decent (white, native-born) citizens.” But it also stands for “us” who must defend “our” country from “them.”

And as Jason Stanley explains, when “us” and “we” become the sole defenders of national heritage and proper social order, the only ones preserving our glorious future and fighting off moral decay, “we” can become more desperate and willing to compromise any remaining moral scruples about means in order to accomplish the necessary ends.

Stanley concludes that one vital step toward full-scale fascism is its normalization; its menacing maturation depends on it remaining unrecognized. That is why contemporary Christian nationalism presents such a pernicious threat; it is already normalized in our public discourse.

Throughout all our studies, our measures of Christian nationalist sentiment seem so innocuous: whether Americans believe the government should advocate Christian values, whether they think religious symbols should be displayed in public spaces, whether they think our nation’s success is part of God’s plan, among others. Most Americans may not sense any underlying threat from embracing such views in isolation.

But in combination these beliefs undergird the characteristics of the Twentieth Century’s most horrifying fascist regimes―the populist demagoguery, the xenophobia, the oppression of minorities, the anti-intellectualism, the jingoist militarism, the authoritarianism.

Whether Christian nationalism develops further along its course will depend on whether Americans recognize it for what it really is. It may talk religion, but it walks fascism.

Samuel Perry is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma. He is on Twitter as @socofthesacred

Andrew Whitehead is an associate professor of sociology at Clemson University. He is on Twitter as @ndrewwhitehead.

[…] books coming out this year on politics and religion is a study of Christian nationalism. Get a preview from authors Samuel Perry and Andrew […]

LikeLike

[…] In a post-colonial, post-Christian world, when it seems like everything is “drifting away” from traditional Christian culture into secularism, fundamentalist Christianity seemed to some like a good idea – Double down, stick blindly to traditional Christianity and impose a “radical” way of life in opposition to the way in the which the world is moving. However, it really is a reenactment of outmoded values and attitudes. Fundamentalism is actually becoming less and less relevant and more and more like a farcical parade. It no more reflects Jesus than the Christendoms of yesteryear. It is clinging to imperfect systems as if they are perfect, and entertaining no critique or sane thought. Fundamentalism may have some things technically right, but the things that it focuses on and how it zooms in on very specific issues is very telling and symptomatic of the rot within its roots and the very shaky foundations upon which it rests. “Purified” culture and “Biblical” ways of life sound good on paper, but the pursuit of these ideals actually has very little to do with Jesus himself or with actual spirituality. […]

LikeLike

[…] answers Let Us Count the Ways the Trump Administration Is Underprepared to Tackle the Coronavirus Christian Nationalism Talks Religion, But Walks Fascism Trump Is Blowing Up a National Monument in Arizona to Make Way for the Border Wall After Iowa, The […]

LikeLike

[…] Trump is actually something else, especially since those feelings are strongly correlated with Christian nationalism. Christian nationalists strongly identify the United States as a Christian protection device – a […]

LikeLike

[…] “Christian Nationalism Talks Religion, But Walks Fascism,” by Samuel L. Perry and Andrew L. Whitehead […]

LikeLike

[…] https://religioninpublic.blog/2020/02/05/christian-nationalism-talks-religion-but-walks-fascism/ […]

LikeLike

[…] since at least the 1920’s, much of the white church in America has functioned as a proto-fascistic current, aligning neatly with what would constitute the base of any fascistic U.S. state: white communities […]

LikeLike

[…] components that make them receptive to the demonization of the other side. One prominent example is Christian nationalism. I measured this with 6 items taken from a Baylor University religion survey that have […]

LikeLike

[…] way we can tell is the strong relationship between beliefs in Trump’s anointing and Christian nationalism – a worldview consisting of deep links between Christianity and the state such that the US is a […]

LikeLike

[…] there are plenty of reasons to be infuriated with a whole lot of Christian churches and people: White supremacy and nationalism; spreading QAnon nonsense; supporting Trump, to name three of the worst. But at Woodridge UMC we […]

LikeLike

[…] the more dangerous association is with Christian nationalism, which marks off the purpose of the US to serve Christians and advance Christianity. Put together […]

LikeLike

[…] [1] For a full explanation and discussion of Christian Nationalism, see Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2020). Our survey questions and analysis mirror their work closely. See also their brief introduction to the concept on this blog. […]

LikeLike

[…] of Christian interests, and reject equal rights for all. Not far removed from this depiction, Perry and Whitehead suggest: “Simply put, Christian nationalism—an ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of […]

LikeLike

[…] Christian Nationalism Talks Religion, But Walks Fascism – Sam Perry and Andrew […]

LikeLike

[…] the Proud Boys knelt in the street in prayer. Many of these people could fairly be labeled Christian nationalists, who were there not just to express outrage over the election, but over what they believe to be the […]

LikeLike

[…] of these people could fairly be labeled Christian nationalists, there to express outrage not just over the election, but over what they believe to be the […]

LikeLike

[…] Christian Nationalism Talks Religion, but Walks Fascism […]

LikeLike

[…] matched Trump’s politics about police, race, immigration, guns, COVID, and other matters as Whitehead and Perry and others have documented. But that worldview has also been attached to approval of violence in a […]

LikeLike