By Melissa Deckman

[Image credit: Fox News]

A truism of the American religious landscape is that Americans are becoming more religiously unaffiliated and that this tendency is especially pronounced among the Millennial generation (born between 1981 and 1996). As demographers turn to the post-Millennial generation, now called Generation Z (born after 1996), can we expect those trends to stay steady or even accelerate? Studies of Gen Z are just beginning, but there’s very little data that examines the religious behavior of this nascent group. I offer a first glimpse. The main takeaway? Gen Z Americans look awfully similar to their Millennial elders when it comes to religious affiliation and religious behavior.

Partnering with Qualtrics Panels, I collected survey data from more than 2,200 Gen Z Americans in late July 2019 as part of a larger study on the political behavior of this emerging generation. Although not a purely random sample, the sample is designed to be representative of the adult Gen Z population in the United States based on gender, race, and region. The data are weighted to match Pew Research Center benchmarks for sex, race/ethnicity, and family income, so it closely resembles the demographic makeup of the U.S. public for the age demographic under study.

Before turning to the data on religious affiliation, it is worth remembering that Gen Z is the most racially and ethnically diverse cohort in America. My survey, again, takes that diversity into account: while a slight majority of survey respondents are white (52 percent), 14 percent are African American, 25 percent identify as Latinx, and close to 4 percent identify as Asian American (which is actually a few percentage points smaller than other demographic studies of this generational cohort). Nearly 4 percent of Gen Z also identify as multi-racial. I’ll circle back to some interesting observation regarding race/ethnicity and religion momentarily.

First, I present the numbers regarding religious affiliation. As a point of comparison, I turn to data collected by Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) in 2016 as part of its American Values Atlas regarding the religious make-up of Millennials aged 18 to 29. As the figure shows below, there are a few differences between my findings and the 2016 PRRI study. For instance, my survey has more white Catholics—11 percent—compared with 6 percent in the PRRI study. This might be related to why my data show a decrease in the number of white Gen Z Americans who identify as Evangelical (5 percent vs 8) or Mainline Protestant (6 percent vs 8) compared with the data from PRRI—but it’s hard to say. Overall, though, 22 percent of white Gen Zers and 20 percent of white Millennials identify as white Christian if we combine all three categories, so there is not much movement between these cohorts.

I also opted to include a new category regarding African Americans in my presentation of the data given that I found nearly as many African Americans who identified as Catholic (2 percent of the sample) as Black Protestant (3 percent of the sample); PRRI’s data omits this group. I also find more Latinx Catholics in my sample, and fewer Latinx Protestants—but if we combine the two categories into Latinx Christians, the Gen Z numbers are similar to PRRI’s findings (15 versus 13 percent for Gen Z). My category of “other Christians” includes Asian Americans who identify as either Protestant and Catholic as well Gen Zers of all races/ethnicities who identify with some sort of Orthodox Christian denomination. I find, too, a slight decrease in this number compared with PRRI’s 2016 results (7 to 5 percent among Gen Z).

I think the more telling finding is that the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey. In other words, it appears that the rate of younger Americans departing from organized religion is holding steady, so conflating Gen Zers with Millennials is not necessarily inappropriate when it comes to religious affiliation—at least so far.

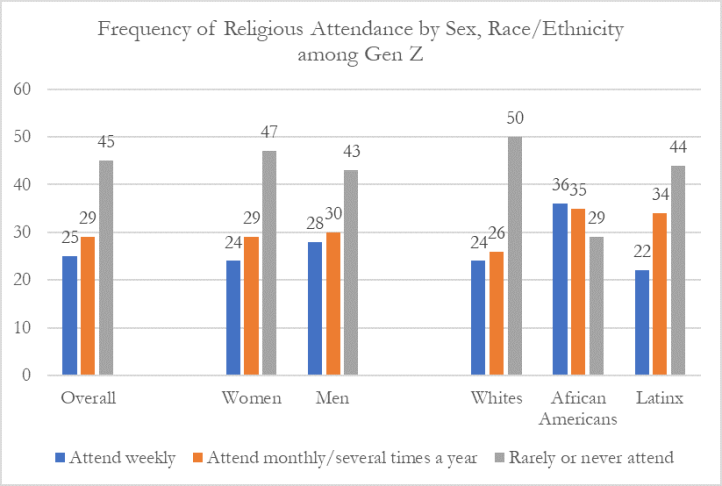

When it comes to attendance at religious services, Gen Z Americans are far more likely to skip church than attend on a regular basis. Overall, I find that 45 percent of Gen Z Americans report rarely or never attending church while just 1 in 4 report attending weekly or more. While these numbers are lower than the national average—studies from the past few years suggest between 36 and 39 percent of Americans report attending church weekly or more overall—they are pretty close to church attendance reports among Millennials, at least with respect to attending church frequently. In 2014, Pew finds that 27 percent of Americans aged 18-29 report attending church weekly or more often, compared with 25 percent of Gen Z Americans. However, there is a jump among those saying they attend church rarely or never. Pew’s 2014 data show that 35 percent of millennials say they attend church rarely or never in 2014, while I find that 45 percent of Generation Z reports rarely or never attending. Whether this drop is related to something inherent among Gen Z Americans is not certain; more recent data from Pew last year shows an increase from 50 to 54 percent of Americans who reporting attending church “a few times a year or less” in the past 5 years.

Given that church attendance has historically differed with respect to race and gender, I also examine my Gen Z data by racial/ethnic groupings and gender. Among my respondents, African Americans report having the highest rates of weekly church attendance, which tracks with other research showing that African Americans attend church more frequently than other groups. At the same time, while 17 percent of African Americans in 2014 reported rarely or never attending church services frequently, 29 percent of black Gen Z Americans report attending church little to none, demonstrating that African Americans are not immune to the growing secularization trends occurring elsewhere among America’s young people—a story that gets relatively little attention from the media or scholars. Church attendance among the Latinx who are Generation Z more closely resembles the church attendance patterns of white Gen Zers, rather than African American Gen Zers, which is consistent with other studies of religious commitment among Americans. Finally, Gen Z men are slightly more likely to report attending church more frequently than Gen Z women, though this difference is only marginally significant (p<.10). This finding is notable, however, because women have always been more religious than men, so Gen Z appears to be bucking this historical trend. Why this might be the case is unclear.

Given that church attendance has historically differed with respect to race and gender, I also examine my Gen Z data by racial/ethnic groupings and gender. Among my respondents, African Americans report having the highest rates of weekly church attendance, which tracks with other research showing that African Americans attend church more frequently than other groups. At the same time, while 17 percent of African Americans in 2014 reported rarely or never attending church services frequently, 29 percent of black Gen Z Americans report attending church little to none, demonstrating that African Americans are not immune to the growing secularization trends occurring elsewhere among America’s young people—a story that gets relatively little attention from the media or scholars. Church attendance among the Latinx who are Generation Z more closely resembles the church attendance patterns of white Gen Zers, rather than African American Gen Zers, which is consistent with other studies of religious commitment among Americans. Finally, Gen Z men are slightly more likely to report attending church more frequently than Gen Z women, though this difference is only marginally significant (p<.10). This finding is notable, however, because women have always been more religious than men, so Gen Z appears to be bucking this historical trend. Why this might be the case is unclear.

Lastly, I present findings from the Gen Z Survey with respect to the religiously unaffiliated, broken down by gender and race/ethnicity. The “religiously unaffiliated” category is a rather blunt designation and incorporates respondents who self-describe as atheist, agnostic, and “nothing in particular.” Analysis of the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study by Ryan Burge finds that 31 percent of the U.S. population overall can be categorized as religiously unaffiliated, although if broken down, 18.6 percent of respondents designate themselves as “nothing in particular,” 6 percent as agnostic, and 6 percent as atheists. Social desirability bias has long compelled Americans to eschew the term atheist; Americans continue to rank atheists more coolly than other religious groups—save Muslims—on feeling thermometers. Yet among Gen Z respondents, I find a greater willingness to embrace that term: roughly 1 in 10 among this generation say they are atheists, slightly higher than the 9 percent of Gen Z Americans who identify as agnostic. As is the case with church attendance, Gen Z women defy historical norms as they are just as likely to be religiously unaffiliated as Gen Z men. However, Gen Z Americans who are white are less religiously affiliated with those who are black or Latinx, which corresponds to historical patterns. African Americans from Gen Z are less likely than their white or Latinx counterparts to identify as Atheists.

As America heads ever more quickly into becoming a minority majority nation with respect to race/ethnicity, with White Christian America becoming a less dominant presence in society, scholars should pay more attention to how minority groups are starting to shift their religious behavior. My data suggest that these groups are looking very different from counterparts in older generations. Moreover, these gender changes with respect to religious behavior—though subtle—also bear more examination. What does it mean for American religion, or civic life more generally, when women become less religious than men? I look forward to more religious data collection to come!

Melissa Deckman is the Louis L. Goldstein Professor of Public Affairs at Washington College and is an Affiliated Scholar with Public Religion Research Institute. Her current work examines how gender impacts the political engagement of Generation Z and Americans’ views about civility in politics.

[…] a companion piece published today on Religion in Public, Melissa Deckman of Washington College finds that the […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older millennials. In both generational cohorts, 38% […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] Survey”, escribió Deckman en un informe publicado por la religión en público, titulado “ Generación Z y religión: ¿Cuál Nuevos datos revelan . […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older millennials. In both generational cohorts, 38% […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older Millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older Millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older Millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] “… the percentage of Gen Z Americans who identify as religiously unaffiliated is similar to the Millennials found in PRRI’s 2016 American Values Survey,” wrote Deckman in a report published by Religion in Public, titled “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show.” […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] she compared those numbers to a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute survey, she found striking similarities between those in her study of Generation Z and older millennials. In both generational cohorts, […]

LikeLike

[…] massive studies, both of which are reported today by the Religion in Public (RIP) blog. In the first, Washington College Professor Melissa Deckman […]

LikeLike

[…] interesting new findings about stability in the proportion of Americans who are religious nones across […]

LikeLike

[…] Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show (Melissa Deckman, Religion In Public): “…it appears that the rate of younger Americans departing from organized religion is holding steady… As America heads ever more quickly into becoming a minority majority nation with respect to race/ethnicity, with White Christian America becoming a less dominant presence in society, scholars should pay more attention to how minority groups are starting to shift their religious behavior. My data suggest that these groups are looking very different from counterparts in older generations.” The author is a professor at Washington College. […]

LikeLike

[…] which broke this past week online by social-science scholars. The stall scenario was asserted by Melissa Deckman of Washington College and immediately pursued by GetReligion contributor Ryan Burge of Eastern Illinois University and […]

LikeLike

[…] (Religion in Public) […]

LikeLike

[…] in Public is an online blog with publications from scholars that pertain to religion. I came across “Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show” by Melissa Deckman, the Chair of the Political Science Department at Washington College. Her […]

LikeLike

[…] generations are known to be less religious. A survey found that 38% of those considered Gen Z and Millenials are unaffiliated with any religion. These generations are […]

LikeLike

[…] “There seems to be a leveling off of rates of disaffiliation,” Deckman said, citing results from a recent survey she conducted on Generation Z. […]

LikeLike

[…] consider themselves Christian, but the majority “hardly ever” or “never” attend church. The numbers for Gen Z are almost identical but will likely increase as more of them leave the home and move into the […]

LikeLike

[…] Generation Z and Religion: What New Data Show – Melissa […]

LikeLike