By Paul A. Djupe, Andrew R. Lewis, and Anand E. Sokhey

**For the next two weeks, you can access our book for free** (~June 15-July 1)

[image credit: Brian Zahnd]

The January 6th Insurrection was “as Christian nationalist as it gets.” The flags, the prayers for dominion over American politics, the shofars all signal a strong link to Christian nationalist ideas. But those stories tend to be missing one crucial element – it was a partisan Insurrection. It was organized to keep Donald Trump in power and fend off the perceived threat to Christians from a Democratic Administration. In our new book, we draw on political science research to push the argument that Christian nationalism is a partisan project. If not designed for this end, it is certainly utilized to mobilize extremely conservative voters. The confluence of partisanship and Christian nationalism promotes both taking particular positions and taking action in American politics to benefit the Republican Party.

It’s not that previous work has ignored some of the partisan implications of Christian nationalism. It has recognized it, and it’s good work. But voting for Trump is only one piece of the puzzle – confining the inquiry to the vote misses a considerable amount of the partisan implications. We also cannot make the mistake of thinking that Christian nationalism = white Republicans. Though white Republicans do admit to considerable Christian nationalism, non-whites and members of the other party (or no party) also have sizable contingents that adopt high levels of Christian nationalism.

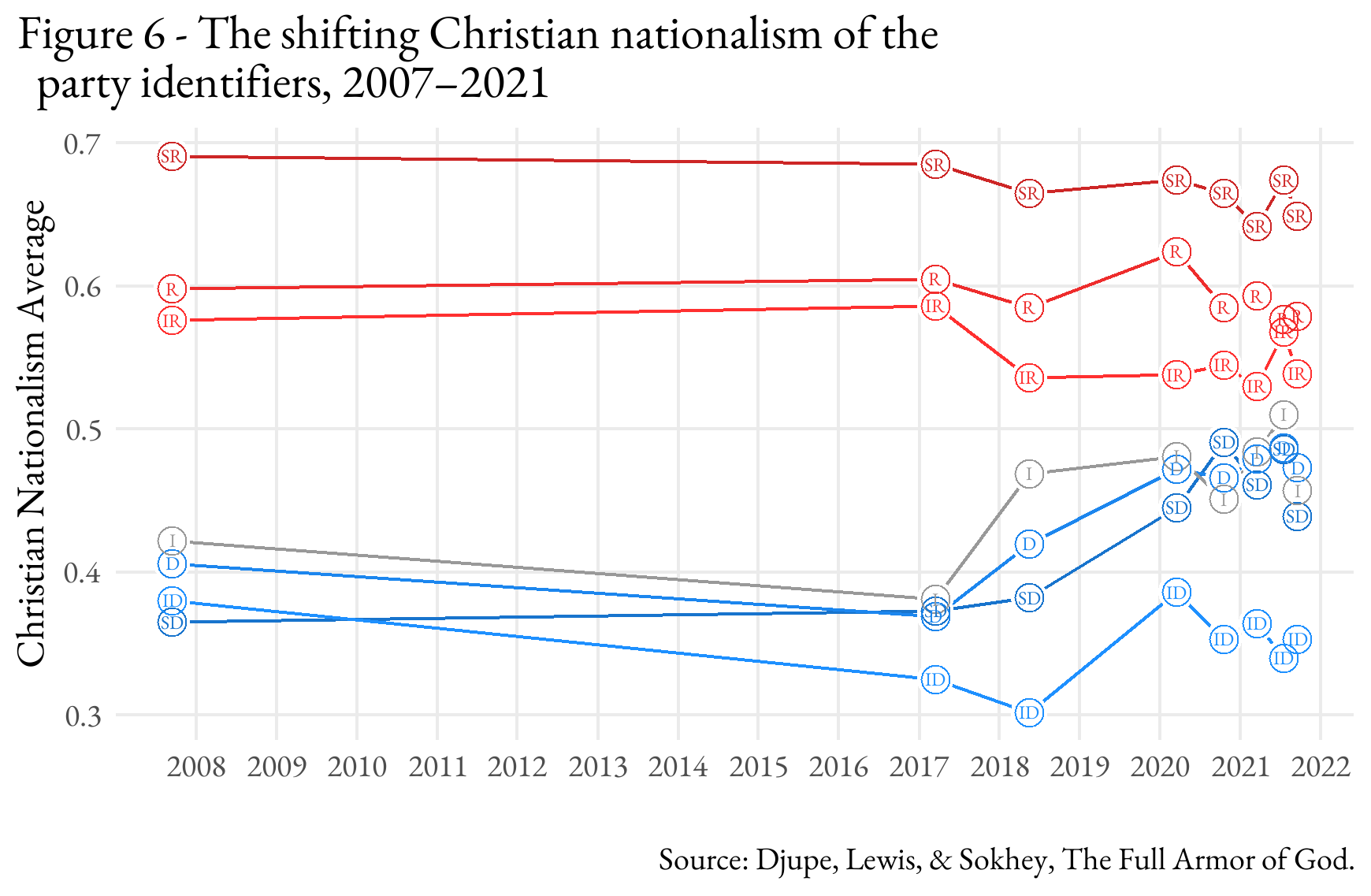

As we show in Chapter 2, a simple story of Republican Christian nationalists vying for power against secular Democrats is just a dog argument that won’t hunt. In fact, according to Baylor and our survey data (see Figure 6 below – we’re using the figure numbers from the book), Christian nationalism GREW among many Democrats during the Trump Administration. The holdout partisan category is independents who lean Democratic, mostly because of the high concentration of the non-religious in that partisan category. This helps us understand why the Democratic Party has appeared reticent to take on Christian nationalism as the threat to democracy that it is – such an argument may alienate a large portion of their identifiers.

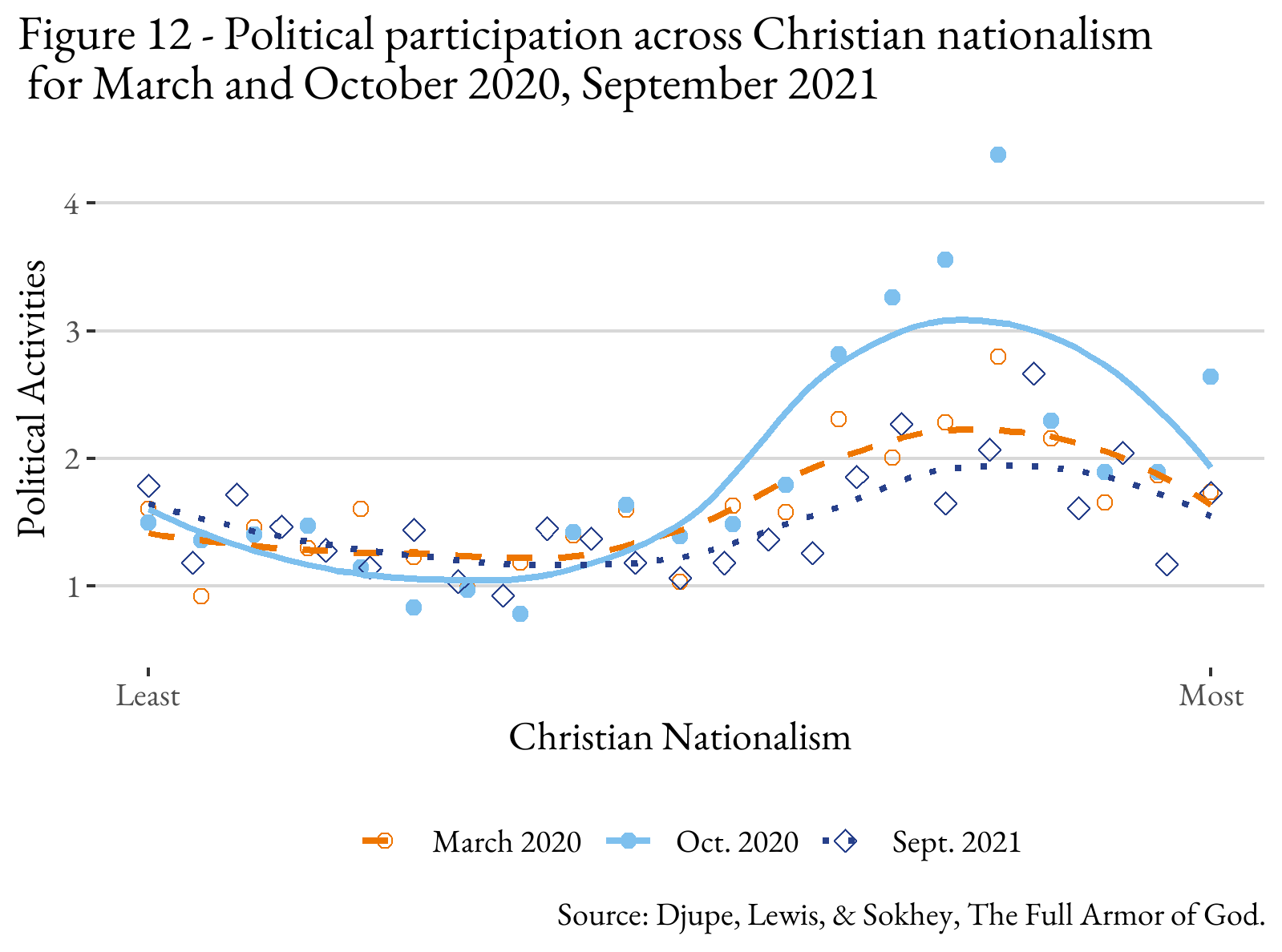

Christian nationalists were being explicitly mobilized to win elections and influence government, as Figure 12 below shows. In each of three surveys conducted around the 2020 election, those who score higher on the Christian nationalism scale participate in political activities at substantially higher levels. And that increase hit a fever pitch in October 2020 when they participated in twice the number of activities as the least CN. We are not content to leave it at that and one of the features of our book is a focus on mechanisms of influence.

What is it about those who score higher on the Christian nationalism scale that make them so participatory? There are lots of forces that are correlated with Christian Nationalism as well as political participation. Some are just demographic differences and, of course, Christian nationalists attend church at higher rates – variation in attendance levels explains about half of the Christian nationalist relationship with political participation. And some of that relationship is driven by political interest as well as the Christian nationalist orientation for social dominance. Their need for power, for the God-granted dominion over the United States, is a powerful motivator to participate.

That’s not all. Republicans are not relying on Christian nationalist dispositions and civil society involvement to keep people involved. Instead, they have been targeting Christian nationalists explicitly with threatening rhetoric. This is something that reviewers get wrong all the time – there is no general, non-partisan argumentation that Christians are being persecuted. Democrats are not making these claims, Republicans are and are blaming Democrats, though perhaps by other names – the left, the woke, the globalists. Trump argued in the runup to the 2020 election that Democrats would ban the Bible and “hurt God.” And that kind of language has not been limited to the 2020 election as Josh Hawley recently claimed that “the left wants to replace God with an idol of their own making” (“wokeism”). A plurality of Americans reported hearing such rhetoric and believing such claims are linked to the much higher rates of political activity among Christian nationalists. It is essential to include the partisan context of these sorts of victimization claims to understand the political implications of Christian nationalism.

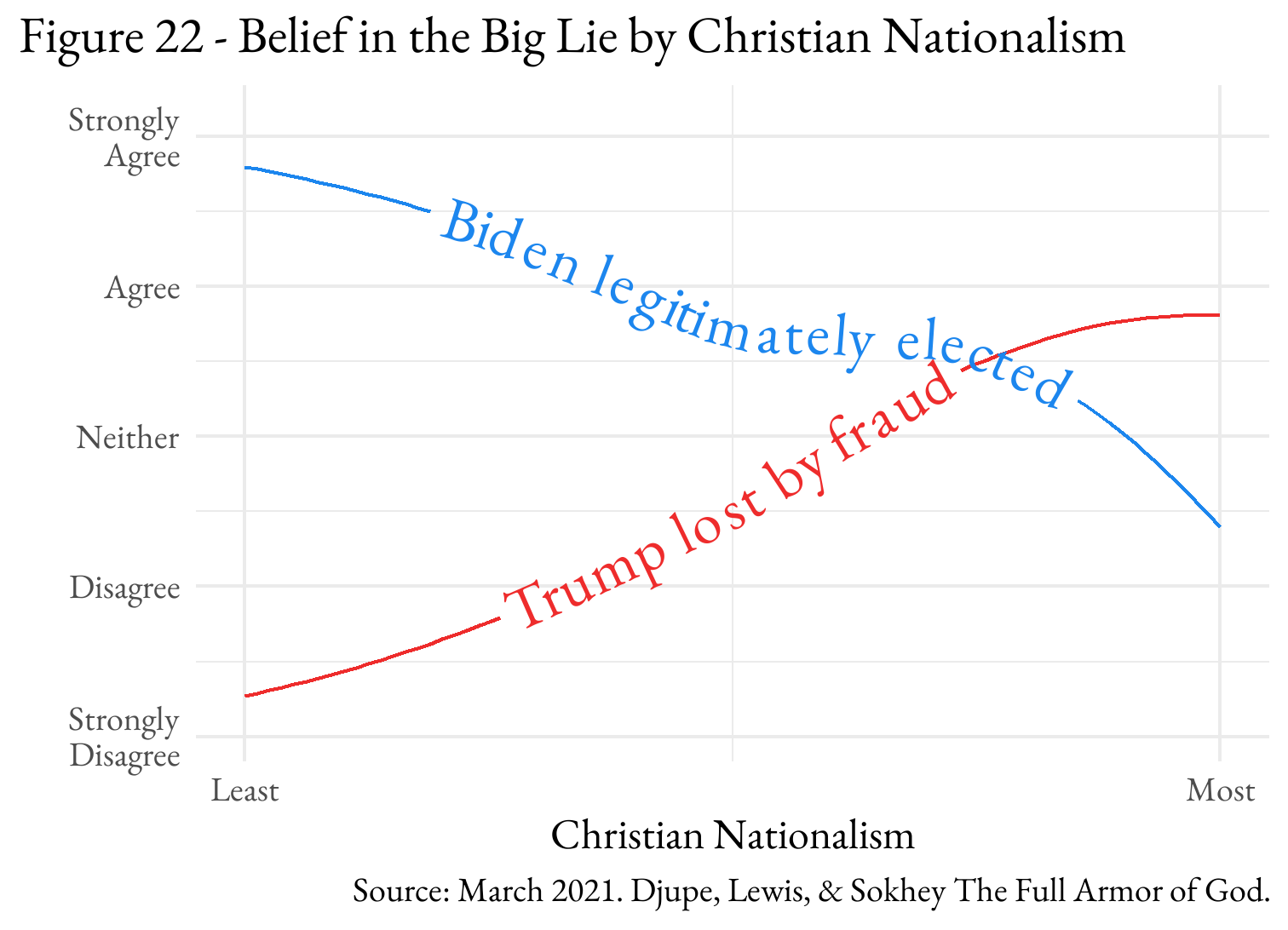

Another way to see that is in their swallowing of the Big Lie, that the election was stolen from Trump (see Figure 22). Ardent Christian nationalists were likely to agree that Trump lost by fraud and disagree that Biden was legitimately elected.

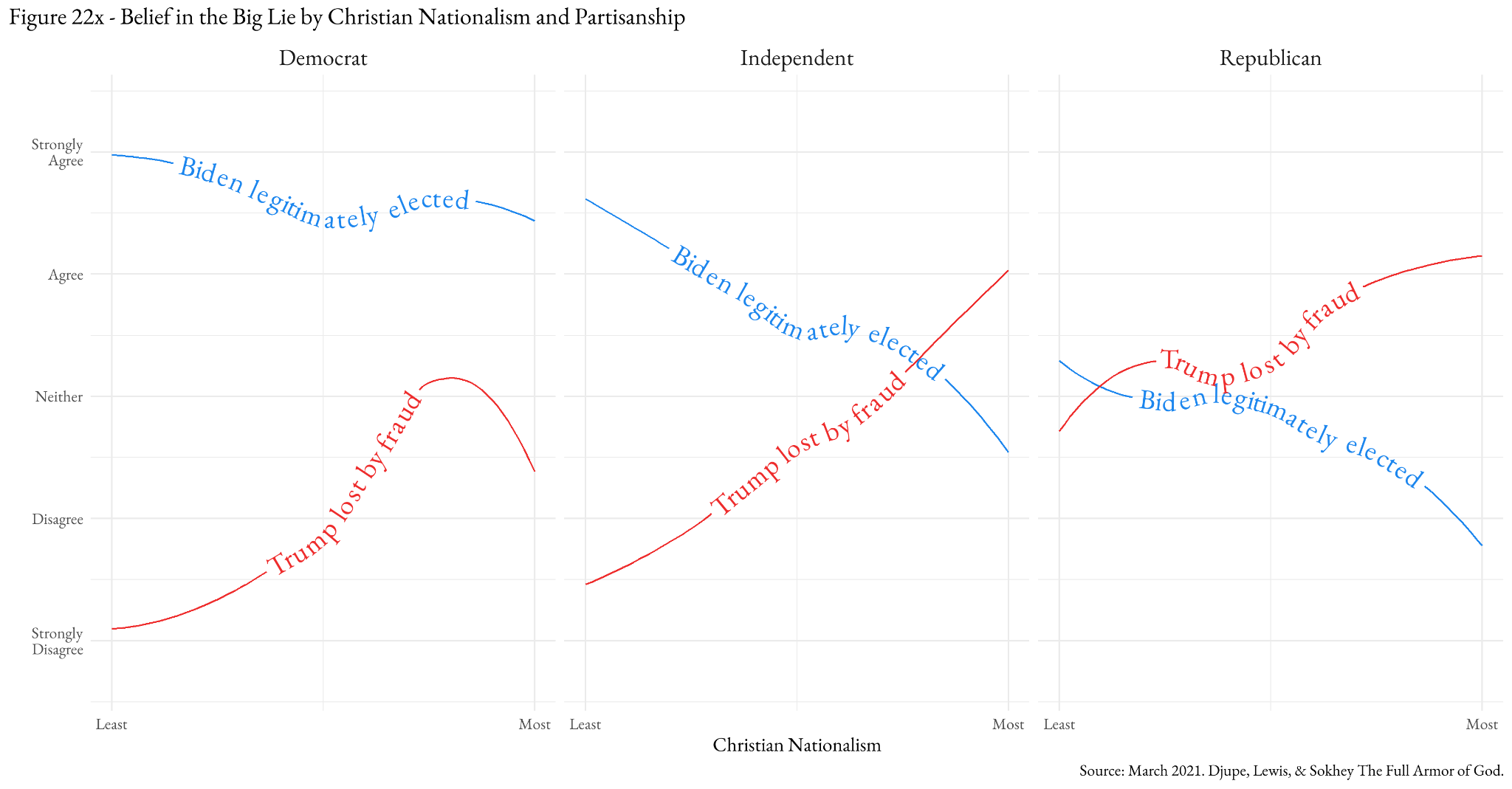

Here’s something we did not do in the book because of space constraints – examine this relationship by partisanship (see Figure 22x). It’s remarkable to see that Christian nationalism puts pressure on Democrats and independents on top of Republicans. While there are fewer Democrats and Independents with high levels of Christian nationalism, the belief that the election was stolen from Trump increases among Christian nationalists in each partisan group, though the average agreement scores are not as high among Democrats as Republicans. While Christian nationalism could be a flexible worldview that empowers the group of the believers, it is abundantly clear that it is a partisan project working in 2020 and 2021 in the interests of the Republican Party and Donald Trump.

The Full Armor of God is short, just 30k words, available in paperback, and is packed with arguments and evidence about the partisan forces working with Christian nationalism and the implications of that relationship. Though we understand a considerable amount of the contours of Christian nationalist politics through solid and wide-ranging research, we have been missing a considerable portion of the story. We have been viewing Christian nationalism like the portraits of college students who crop out their best friend. They are both at the same party. You can’t understand the success of Republican politics without understanding Christian nationalism and cannot understand CN without considering the needs of the Republican Party.

Professor Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found on his website and on Twitter.

Andrew R. Lewis is Associate Professor in the School of Public and International Affairs at the University of Cincinnati. He is currently the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the political science journal Politics and Religion, as well as the author of The Rights Turn in Conservative Christian Politics: How Abortion Transformed the Culture Wars (Cambridge, 2017). Further information can be found on his website and on Twitter.

Anand Edward Sokhey is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is the Director of CU’s American Politics Research Lab and a faculty fellow at CU’s Institute for Behavioral Science. Further information about his work can be found on his website and on Twitter.

[like] R. Brown reacted to your message: ________________________________

LikeLike