By Paul A. Djupe, Ryan P. Burge, and Christopher R.H. Garneau

For more than half a century, public surveys have asked some variant of “What is your present religion, if any?” The foundation of religious measurement in surveys presumes that individual responses accurately describe the religious community in which respondents are involved. So when they are asked how often they may attend worship services, the answer (e.g., “a few times a year”) is assumed to be in a congregation described by their religious affiliation. If they say they are Catholic, they are attending a Catholic parish, right? But what if it doesn’t mean that?

In our new research to be published open access in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, we report on two recent surveys of American adults – one of 4,000 adults in February 2022 and one of 2,300 adults in March 2023, both through Qualtrics Panels. In both, after asking about their religious identity (Protestant, Catholic, Jew, Muslim, etc.), we asked “Would you say that you attend a congregation that shares the religious affiliation that you just provided?” In both surveys, after omitting the portion of the sample that does not attend any congregation, we found that about a fifth of worship-attending Americans indicated that it does not (20 percent in the 2022 survey and 18 percent in the 2023 survey). That is, twenty percent are attending a congregation that does not match their religious identity.

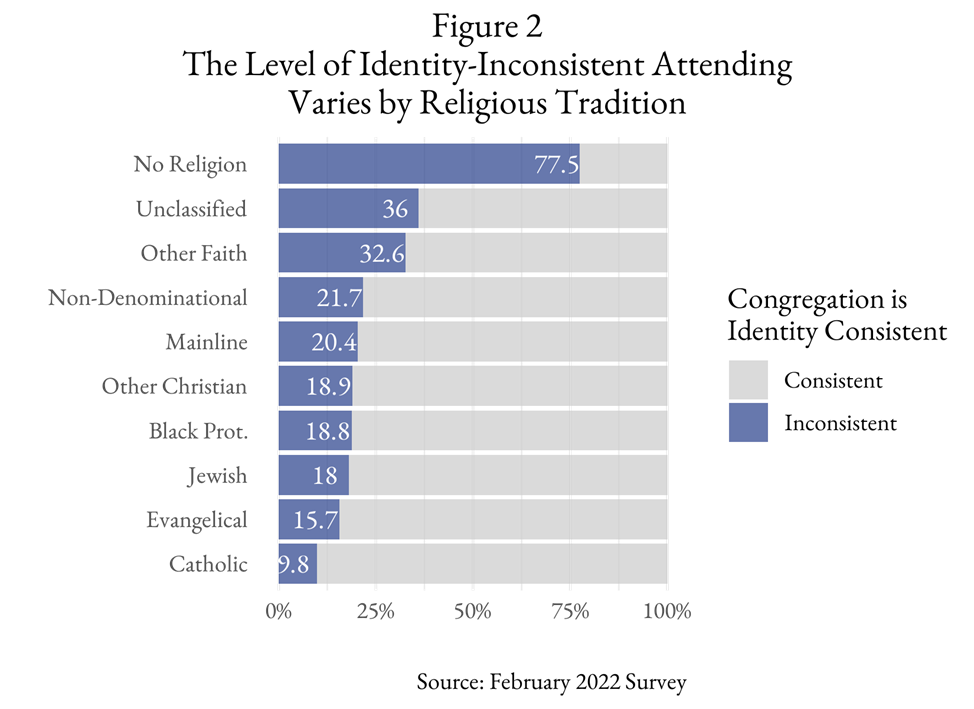

It is no surprise that “identity-inconsistent attending” is more common among those with no religious identity – it applies to essentially all of the worship attending non-religious. But it also applies to a fifth of most sizable Christian groups too, including 22 percent of non-denominationals, 20 percent of mainline Protestants, and 19 percent of Black Protestants. It only applies to 10 percent of Catholics.

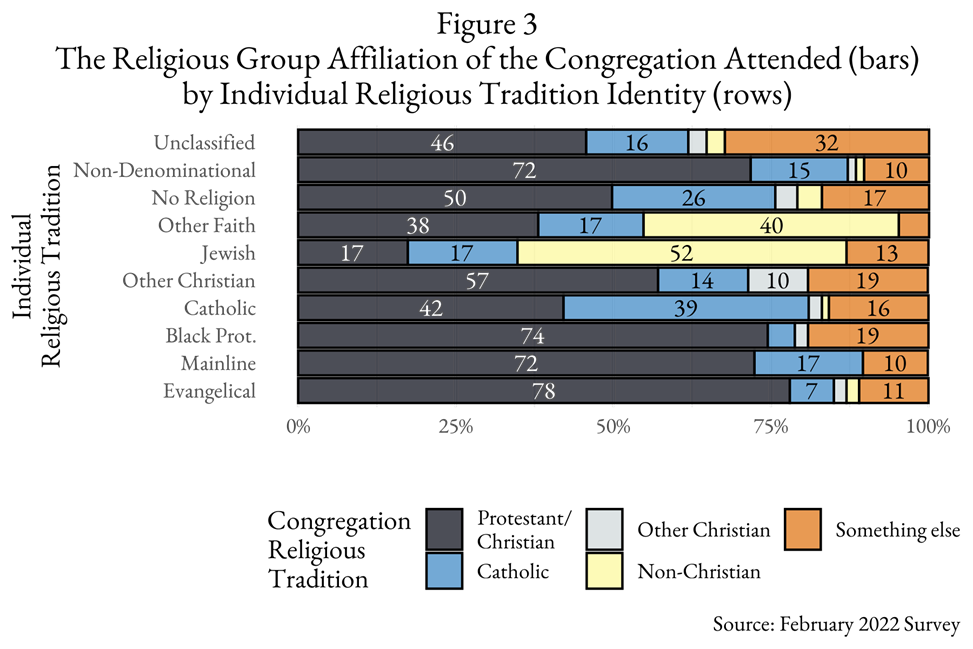

Now, the religious distance of identity-inconsistent attenders from their current congregation to their religious identity may not be great. Most identity-inconsistent Protestants (bottom three rows of the figure below) attend a congregation affiliated with some other Protestant denomination. But some jump out of the broad religious tradition entirely to attend a Catholic parish or something else. In either case, the congregation they choose to attend may be quite different from the one they presumably left that was identity-consistent.

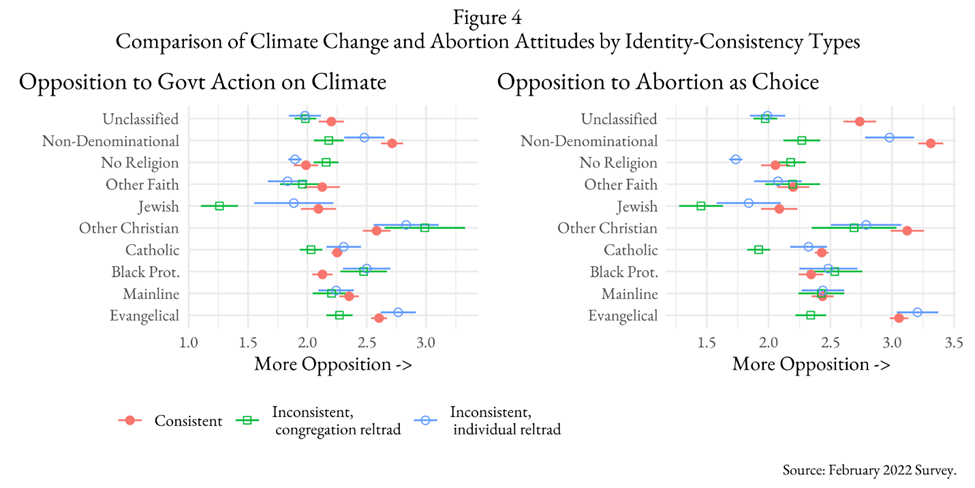

Does it matter if they attend something other than a congregation that matches their religious identity? If there is no daylight between identity-inconsistent attenders and consistent attenders, then this is all ado about nothing. But if there are gaps, then we should be concerned. In the figure below, we use attitudes on two issues – abortion and climate change – to look for gaps (we use more in the article). There are three estimates provided for each line:

- Consistent – identity and congregation match (e.g., Catholic identifiers who attend a Catholic parish).

- Inconsistent, congregation religious tradition – their identity doesn’t match the congregation and we are showing the average score of the congregations’ religious traditions (e.g., non-Catholic identifiers who attend Catholic parishes).

- Inconsistent, individual religious tradition – their identity doesn’t match the congregation and we are showing the average score of the individual’s religious tradition for all the inconsistents (e.g., Catholic identifiers who attend congregations in other traditions).

It is clear in most cases (see figure below) that these three groups are not on the same page about these two issues. For instance, among non-denominationals, the identity- consistent attenders are the most opposed to the government taking further action on climate change and abortion, while the inconsistents are more in favor. The gap to the congregational measure of inconsistency is quite large on abortion for non-denominationals. That pattern flips for Black Protestants on climate change. In both issues, mainline Protestants show almost no variation across the three groups. In the main, we can find significant gaps between the three groups across these two issues. Assuming all religious identifiers are consistent attenders produces misleading estimates of their policy views.

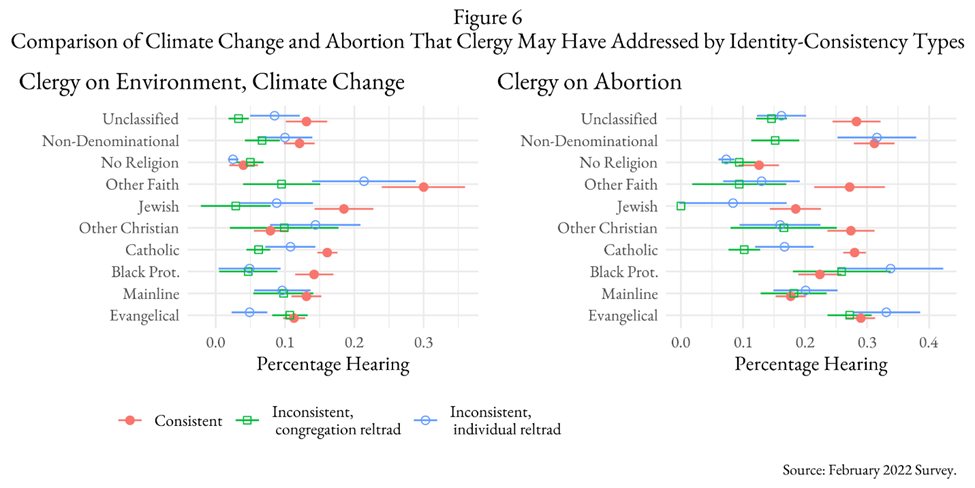

Another reason why identity-inconsistent attending may matter is by returning misleading estimates of what happens in the congregations, such as clergy communication. We repeated the same style of analysis for clergy communication as above with policy attitudes. The surveys asked if they heard their clergy discuss a variety of policy issues and we grabbed a range of them to analyze (two here and more in the article). Again, as shown below, the estimates of clergy communication vary quite considerably depending on their identity-attendance consistency. In this case, however, consistent attenders almost uniformly report hearing more. As above, consistency does not matter among mainline Protestants, but it does among many others. About half as many inconsistents who attend a Catholic parish report hearing about the environment compared to consistent Catholics, for instance. That gap is even greater concerning abortion. Again, assuming identity consistent attendance would produce misleading estimates of clergy communication on public policy matters.

There is a lot more to the article, including considerable discussion of why people might become identity-inconsistent attenders and exploration of what our data can tell us. But we are more focused on the implications. Religious tradition questions are the foundation for most depictions of religion in public life. Pew, PRRI, and many others often begin (and usually end) with a breakdown of how people differ by religious tradition. The assumption, rarely stated because it is an article of faith, is that the religious identity question governs religiosity and worship attendance. If you say you are a Southern Baptist, these measures assume your attendance report refers to a Southern Baptist congregation. Not so fast. While most people are identity consistent in their attendance, a substantial minority is not and their political attitudes and reports about their congregations differ in consequential ways. This phenomenon contributes to biased reports about what religious traditions are thinking and doing in public life. As a result, we strongly recommend a fundamental rethinking of the religious tradition approach to religious measurement.

Professor Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found on his website and on Twitter and Threads.

Ryan Burge is an associate professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and the research director for Faith Counts. He is the co-creator of religioninpublic.blog and is the author of several books including The Nones.

Christopher R.H. Garneau is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma. Much of his work deals with the intersection of American politics and religion. See more about his work here.

Image note: This cover image was generated from a prompt submitted to DALL-E.