By Brooklyn Walker and Donald P. Haider-Markel

There’s no question that the United States is changing. Historically, most representations of the country have assumed that Americans are overwhelmingly White and overwhelmingly Christian. But in the past 50 years, the US has become dramatically less White and less Christian. At the same time, we see evidence that White Christians are not doing OK. Many White Christians support the idea of Christian nationalism, which claims that Christianity should exert dominance by defining American political institutions and policy. They also fear that their racial and religious group are facing persecution, despite strong evidence of White and Christian privilege. Why?

Two stories are told. The first centers changes to the religious character of the country. Since its founding, the US has purportedly been majority Christian, and symbolic expressions of Christianity (like the reading of the Bible in public schools) have long been present in political institutions. The connection between patriotism and Christianity escalated in the 1950s. President Dwight D. Eisenhower integrated ‘under God’ into the Pledge of Allegiance, inscribed ‘In God We Trust’ on American currency, and initiated the National Prayer Breakfast to demarcate a Christian United States from a godless Soviet Union. A decade later, the Supreme Court challenged this long-standing public acknowledgement of religion, Christianity in particular, by banning school prayer and Bible reading. By the 1990s, religion had begun a steep decline, both in public spaces and in private hearts. Alarmed at their declining status, Christians rallied around calls for a Christian America.

But a second story has emerged. In this telling, the 1960s not only witnessed challenges to religious hegemony, but also to White hegemony. This was the height of the civil rights era, culminating in enforcement of school desegregation and the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. As Martin Luther King Jr. lamented, opposition to Black equality was concentrated among White Christians. Alarmed at this threat to White supremacy, White Christians looked for ways to mobilize. Because explicit calls for racial hierarchy would be socially unacceptable, White Christian elites sounded alarm bells about prayer in school and abortion access, knowing that White Christian voters would also vote in line with their racial group interests. Some scholars have argued that this sleight-of-hand continues today, with calls for a ‘Christian America’ ultimately expressing alarm at the racial diversification of the United States.

In both cases, White Christians feel threat – in the former, on the basis of their religious identity, and, in the latter, on the basis of their racial identity. What weight does each of these stories have in explaining Christian nationalism support? The problem is that both of these changes (secularization and racial diversification) have been occurring at the same time, and previous studies have not compared one story to the other.

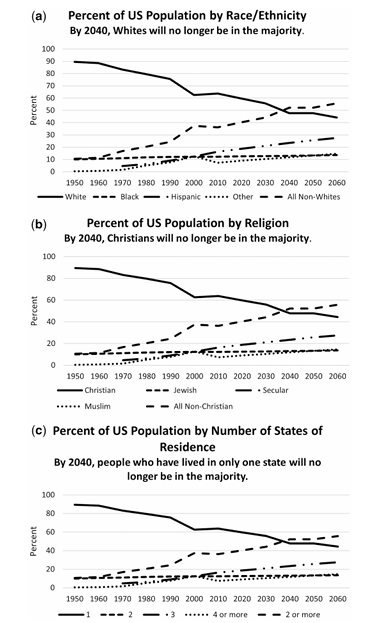

To tackle this question, we designed an experiment to be embedded within a survey now published in Public Opinion Quarterly. We used real-world data to create a graph shown to participants highlighting the fact that the US is destined to become a majority-minority country in the near future. This graph illustrates racial demographic change. Then we took our race graph and changed the labels to signal religious demographic change, i.e., that the US could become a non-Christian-majority country. Finally, following other demographic experiments, we used state residence mobility labels on our control graph. You’ll note that these graphs are identical, except for the labels. That means that any differences we see should be because our White Christian respondents are made aware of different kinds of threats to their group status.

Our survey was fielded online and 416 White Christian participants were randomly assigned to see one of the three graphs. Afterward, we asked them how they felt about the information they learned – were they sad, worried, disgusted, angry? We used statistical models to control for respondent characteristics and predict their emotional and attitudinal responses.

Respondents who saw the racial demographic change graph didn’t report emotional states that differed in any substantive way from the control group. In other words, they weren’t seeming to express feelings of threat in response to rising racial diversity. But the people who learned that Christianity is in decline had strong emotional reactions. They were much more likely than the people in the control group to say that they felt anger, disgust, and especially worry and fear. Among our White Christian respondents, the threat to a Christian America was more alarming than the threat to a White America.

We were also interested in participants’ support for Christian nationalism, perceptions that White Americans are discriminated against, and perceptions that Christian Americans are discriminated against. We started by comparing the respondents who saw the graph about racial change to the respondents who saw the control graph, and found that they weren’t any more likely to espouse Christian nationalism or to believe that Christians were persecuted. They didn’t even express more fear that White Americans would be persecuted.

But people who were told that the number of Christians is declining had very different reactions, depending on their emotional state. Feeling fear about Christianity’s decline led to less support for Christian nationalism, but disgust elevated Christian nationalism support. Disgust also spilled over into seeing a world hostile to Christians. But our respondents weren’t directly connecting changes to the religious composition of the country to race – they didn’t believe that a less Christian America would persecute White Americans.

None of this is to say that race doesn’t matter. In all of our models, we include a measure of racial resentment. Racial resentment predicts Christian nationalism, Christian persecution beliefs, and White persecution beliefs. In other words, negative stereotypes about Black Americans are related to Christian nationalism and persecution beliefs. But while Whiteness and Christianity are undeniably intertwined among Whites, our experiment provides evidence that they cannot be conflated. White Christians perceive the threats to their racial and religious groups differently, and those threats affect attitudes differently. As the country continues to move away from Christianity, we anticipate that White Christians will experience secularization as a threat to Christians and seek to formalize Christianity’s privileged status.

Brooklyn Walker is an Instructor of Political Science at Hutchinson Community College. Her work focuses on religion and politics, public opinion, and political psychology, with a focus on Christian nationalism. To learn more, visit brooklynevannwalker.com or follow her on Twitter @brooklynevann.

Donald P. Haider-Markel is Professor of Political Science at the University of Kansas. His research and teaching are focused on the representation of group interests in politics and policy, and the dynamics between public opinion, political behavior, and public policy (see https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Donald_Haider-Markel); follow on twitter @dhmarkel.