By Brooklyn Walker

“Christian nationalism is, at its heart, White supremacy” has almost reached the status of truism in the field of religion and politics. Christian nationalists are more tolerant of racists, support racially-coded spending, and believe that reverse discrimination is a significant problem. This desire for strict racial boundaries trickles all the way down into private life, with Christian nationalists disapproving of interracial marriage and adoption. In a recent article, I showed that even just the sight of Black people was enough to trigger prejudiced people to become more Christian nationalist.

And yet, in survey after survey, Black Americans are more supportive of Christian nationalism than White Americans. Now you might be thinking, ‘Yes, but Black Americans express higher levels of religiosity than White Americans, so Christian nationalism support is probably just reflective of religiosity.’ You would be correct that Black Americans are highly religious, but their high Christian nationalism support remains even after controlling for evangelical identification and religious service attendance. So why do Black Americans express support for Christian nationalism?

In an article out at Political Behavior, I argue that Black Christian nationalism support is a result of White supremacy. When someone feels that their belonging to a group is challenged by someone else, a common response is to find some way to assert that they do indeed belong. In some cases, you can’t change the attribute of yourself that is being used to exclude you. But you can emphasize other identities that show that you belong to the group. I’ll give you a personal example. Several years ago, I was a news junkie with a master’s degree in political science. I was also a member of my local homeschool co-op. My academic credentials led group leaders to question whether I fit – so much so that my co-op US Politics class got pulled from the schedule. So at co-op outings I never talked about myself as a political scientist – instead, as a Christian, I discussed the happenings of my local church. When my identity as a co-op member was challenged because I might be ‘one of those liberal academics’, I asserted my group membership by drawing attention to a different identity category – Christian.

It turns out that there’s a large literature in psychology about identity management describing this cycle of identity denial and identity assertion. I began to wonder if some Black Americans’ reactions to exclusion might not be dissimilar to my own, and specifically if Christian nationalism might be a way to demonstrate Americanness. In 2020, I devised an experiment to test the effects of two different types of American identity denial on Christian nationalism support. Ethnonationalism, or the belief that being American requires ascriptive characteristics like being White, is a clear example of identity denial. One-third of my respondents read the following ethnonationalist statement:

There has been some discussion about what being American is. Some people make the following statements about being American: “American national character is based on shared ethnic and cultural identities. For America to hold together as a single country, Americans need to share some common traits. Early in American history, European settlers created American government and culture, and this is why people who weren’t born in the US and some racial and ethnic groups don’t have as strong of ties to American identity.”

Civic nationalism is the belief that being American is about adopting a set of ideas, like equality and meritocracy. On their face, these seem quite inclusive. After all, anyone, regardless of skin color or location of birth, can support democracy, rule of law, and work ethic. But many of these ideas are actually tinged with racial meanings. For example, leading measures of racial resentment ask questions about whether Black Americans are just not hard workers, and this statement gets broad support amongst the American public. There are also well-established tropes of Black criminality, with the implication that Black Americans aren’t really living an American way of life. Because civic nationalism has racial undertones, I expected that civic nationalism would prompt some identity denial. One-third of respondents were randomly assigned to read this civic nationalism treatment:

There has been some discussion about what being American is. Some people make the following statements about being American: “American national character is based on liberty, equal treatment for everyone no matter their background, democracy, and respect for American institutions and laws. Americans hold these values to be self-evident. Anyone who adheres to these values is a real American, regardless of their background, where they were born, or their racial or ethnic group.”

And, finally, one-third of respondents were assigned to the control group. This group jumped directly to whether they agreed with several measures of Christian nationalism: The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation, The federal government should advocate Christian values, and The federal government should allow prayer in schools.

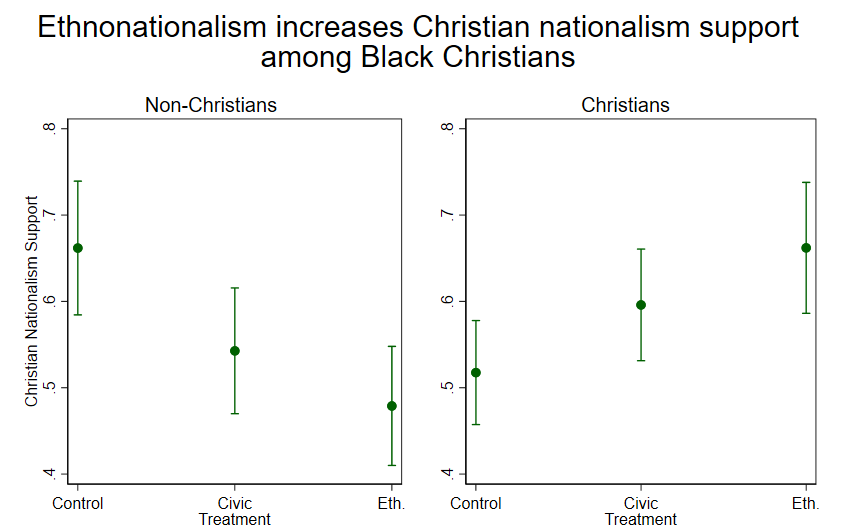

When Black Christians are exposed to civic and especially ethnonationalism, they become more supportive of Christian nationalism. Believing that the United States is a Christian nation places (Black) Christians at the center of the country. Non-Christians wouldn’t find their belonging as Americans more secure in a Christian America, but less – perceiving this overlapping exclusion, their Christian nationalism support drops.

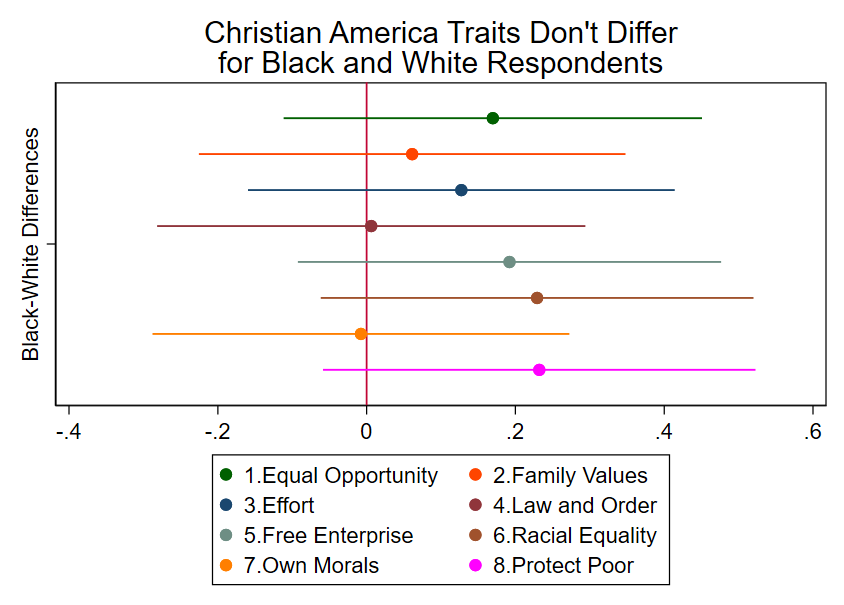

Some prior work suggests that Christian nationalism may have an entirely different meaning to Black and White Americans. If that’s the case, then perhaps Black Christians are affirming something entirely different than the hierarchical version of Christian nationalism we are more familiar with. But I also find evidence to suggest that Black and White respondents’ understandings of a Christian America aren’t all that dissimilar. On a different survey, also fielded in 2020 (N=1,530), I asked respondents how characteristic various traits were of a Christian America. The figure below is a coefficient plot showing the effects of being Black (compared to White). There are some traits Black respondents felt were more emblematic of a Christian America, including a country that protected the poor and ensured racial equality. But in every case, the difference between Black and White evaluations wasn’t statistically significant.

This piece makes a few important contributions. First, it highlights the similarities between civic and ethnonationalism. Unfortunately, while it could be the basis for an inclusive support for the country, civic nationalism is not racially-neutral. The research also highlights the complexity of individuals. Most identity research to date has focused on a single identity category. But people carry around a host of different identities, each of which can be made salient or leveraged in different circumstances. Paying more attention to complex identities can provide important insights into how people navigate their social landscapes.

At the end of the day, the United States has a long history of excluding Black Americans from full national membership. Historically, slavery, Supreme Court decisions like Dred Scott v. Sandford and Plessy v. Ferguson, and Jim Crow laws meant that access to the basic rights of citizenship were denied to Black Americans. Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1965, and other governmental actions have gone some way toward creating greater de jure racial equality. But the idea that Black Americans just don’t quite fit in has turned out to be much harder to change than laws, and those signals have profound effects for the people denied full belonging.

Brooklyn Walker is an Instructor of Political Science at Hutchinson Community College. Her work focuses on religion and politics, public opinion, and political psychology, with a focus on Christian nationalism. To learn more, visit brooklynevannwalker.com or follow her on Twitter @brooklynevann.