By Paul A. Djupe, Denison University

Due to the power of The Atlantic, many more Americans have become acquainted with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) featured in Stephanie McCrummen’s excellent piece The Army of God Comes Out of the Shadows. She is not the first to cover this independent Charismatic movement, but her story caught some readers off guard given the inclusion of statistics about its estimated extent in the US. Those statistics came from me, using survey questions I worked with Dr. Matthew Taylor to construct.

In the weeks since publication, I’ve gotten a number of emails from thoughtful people asking for further information because they were surprised to learn that 40 percent of Christians agree that “God wants Christians to stand atop the ‘7 Mountains of Society’ (government, education, business, etc.).” One important piece of information I shared with them is that the estimate of Seven Mountains (7M) support from a Christian sample in January 2024 (40 percent agreement) is very close to that gleaned from the Christians in a broader sample gathered in October 2024 (42 percent agreement – both samples are weighted). That is, I have replicated the estimate with a new sample. And my estimates are similar to those offered by PRRI, who use a slightly different wording without elaboration of the mountains: “God wants Christians to take control of the ‘7 mountains’ of society.” They find that 48 percent of evangelicals agree with their question, while I find in both 2024 samples that 53 percent of evangelical identifiers agree with my version.

But there have also been a few pieces written criticizing these figures and rejecting them based on evidence-free claims. In a piece titled “How NOT To Count American Religious Extremists,” history professor at Baylor, Philip Jenkins, responds: “That is, um, VERY counter-intuitive, right?” In the end, Jenkins admits that “I have no idea of the exact number of American Christians who espouse the NAR, but it is assuredly not forty percent. A guesstimate might point to two or three percent, but that would be on the high side.” Jenkin’s logic is simply that, as he asserts, “it is not legitimate to say that such a number ‘accepted Seven Mountains ideology’ or anything vaguely like that.” In another piece, law professor John Inazu makes a similar assertion.

Because I attempt to be a reasonable social scientist, I try not to make assumptions, but to test hypotheses. So, do people who agree with the Seven Mountains (7M) adopt a 7M worldview? I’ll focus on three questions that help to begin to answer this question (though if this were an academic article, I’d add a lot more). The first looks at agreement with the statement, “The offenses listed in the Bible should be punishable by government today through the courts.” The 7M is at heart a dominion theology and nearly two-thirds of those who strongly agree with it adopt this clear measure of theonomy (rule by religious law). In fact, that’s true with a broader theonomy scale, too – 7M believers score .71 (0-1 range) compared to a score of .06 for those who reject 7M. That is, 7M believers are highly likely to adopt dominionist viewpoints even if they may not believe in every dominionst view presented in the survey, which went as far as, “The United States should only award full citizenship to Christians” (with which 42 percent of 7M believers agree). This is not the pattern we would see if people thought 7M just meant Christians should just flourish in society.

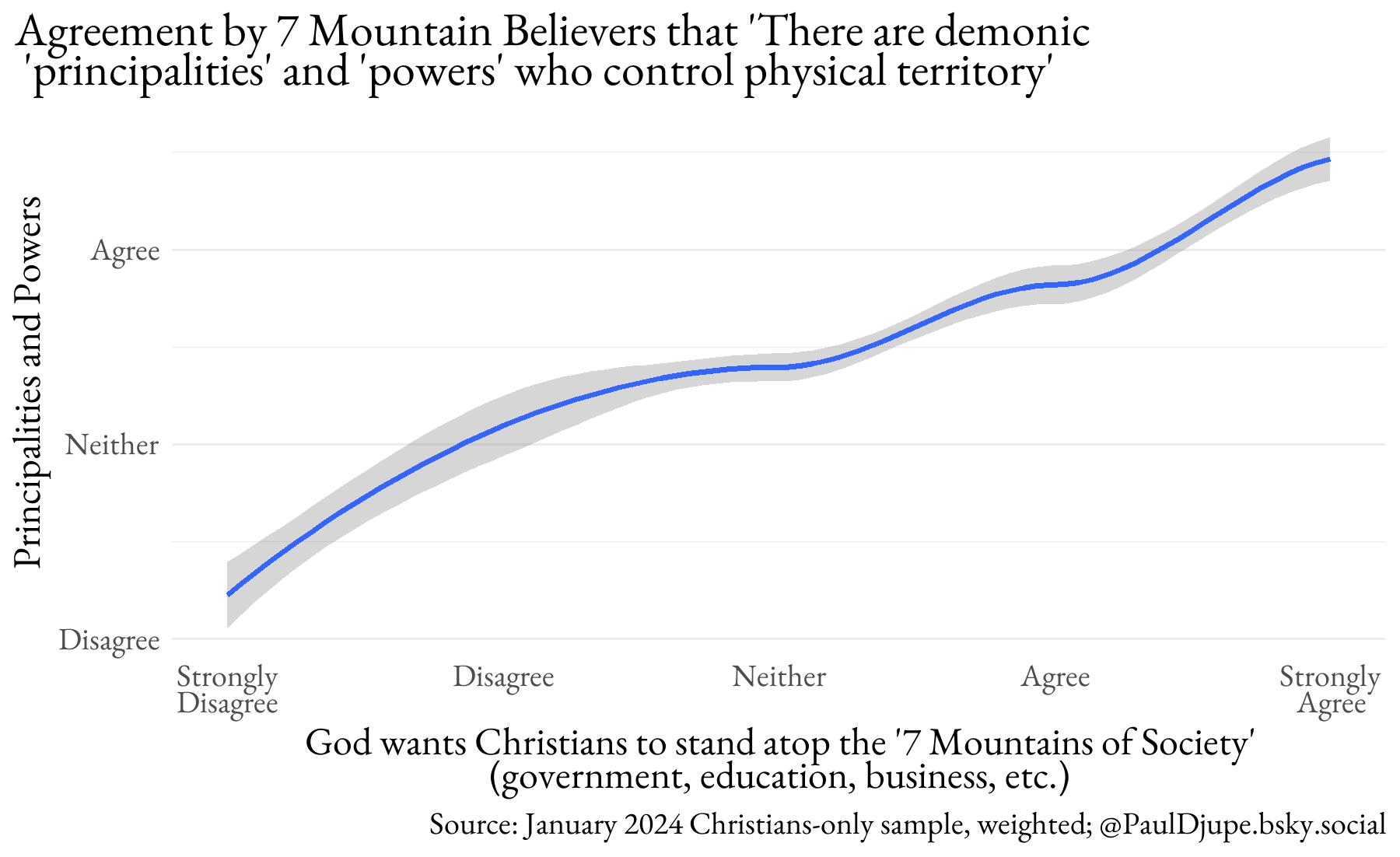

A second item approaches questions about 7M from a religious angle. One innovation by NAR co-organizers C. Peter Wagner and Cindy Jacobs was to expand the notion of demonic control beyond people to nations in the form of “strategic spiritual warfare.” In his piece, Mark Oppenheimer is quite wrong to suggest that this idea is not associated with the NAR. Does 7M agreement tend to appear along with agreement that “There are demonic ‘principalities’ and ‘powers’ who control physical territory”? From the figure below, it is clear that those who reject the 7M also disagree with the existence of demonic control of geography, while those who agree with the 7M tend to agree with that notion. People are not just answering questions, but are reporting their adoption of a broader religious worldview.

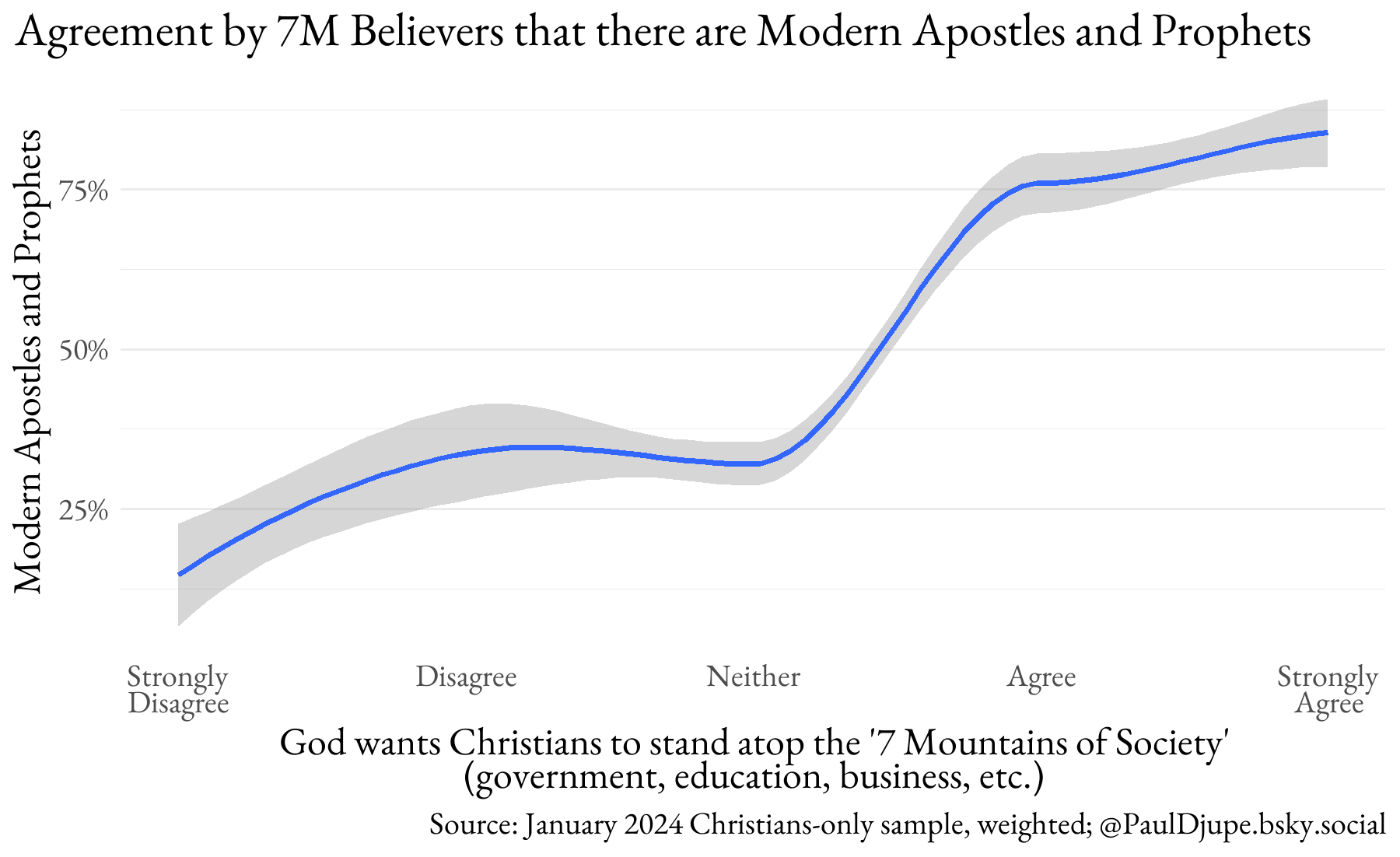

The third addresses the critique of using a set of items to capture prophecy belief. In Jenkins’ estimation, those could mean anything and therefore distinguish nothing. This is a critical test because, according to expert Matthew Taylor, the NAR popularized a cluster of ideas about apostolic/prophetic leadership, strategic spiritual warfare, and 7M-style dominion theology. And those ideas proved crucial building blocks for the core theology of Christian Trump support. Do people link the idea that there are modern apostles and prophets to perhaps the most famous prophetic meme to emerge from the NAR (7M)? The figure below shows a step change pattern so that only 7M believers show super-majority agreement with the idea that “There are modern-day apostles and prophets, and they should be integral to church leadership today.”

The NAR is an incredibly difficult thing to study, in part because it does not even call itself the New Apostolic Reformation. No one is “espousing the NAR.” That term, as Matthew Taylor explains in his powerful new book The Violent Take it by Force, was a branding term that C. Peter Wagner and close associates invented at a lunch in 1996 to help interest religious leaders in adopting its way of doing church. Wagner later applied this same “New Apostolic Reformation” title to a network of affiliated religious leaders he built in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Wagner died in 2016, but as Taylor shows, these networked leaders continued to endorse and promote each other and share ideas, including in their very important role in mobilizing Christians for January 6th. Though the NAR does have some loose organizational structures, Wagner self-consciously organized it as a sort of anti-denomination as they believed charismatic leaders should be at the apex of the church without institutional checks or regulations.

It is also difficult to study precisely because its ministries are not limited to congregations, but also involve social and traditional media in addition to regular traveling roadshows and campaign rallies. Therefore, people can be exposed to independent charismatic ideas from many different sources and may not know they are receiving ideas from charismatics or who originated the idea. But this is also the power and genius of the NAR framework. Leaders self-consciously share ideas that appear to be working through contact, reading the voluminous publishing, and through observation. Taylor documents one such instance in the 1990s called the “10-40 window” that spread through Christian and especially evangelical channels, enlisting tens of millions of evangelicals globally in their prayer and spiritual warfare campaign. So when, in his post, law professor John Inazu finds it unlikely that a book laying out the 7M mandate could reach so many people, he fundamentally misunderstands how information spreads through the NAR networks. In fact, if you poke around even a few minutes on the internet, you’ll find that there are literally dozens of books now with Seven Mountains either prominently in their titles or intensely referenced within. Mark Oppenheimer makes the same mistake, guessing that because few could name NAR leaders means that no one could possibly understand the meaning behind prophetic memes like the 7M.

This is why researchers should use a variety of ways to estimate the reach of ideas generated from NAR-linked religious leaders. One could be the belief in modern prophets and apostles. Others include belief in the Seven Mountains, strategic spiritual warfare against demonic control of physical territory, the billion soul harvest, and more. Communication of these ideas may not come from within a congregation, but may come from books, social media posts, conferences, countless YouTube videos, politicians, or someone else. In this way, the power of the NAR is its loose affiliations (what social scientists call ‘weak ties’) – information can spread far and wide when networks are not hemmed in by, for instance, denominational ties.

In a time of church mobility, rapid growth of non-denominationalism, spread of mediated religion, religio-political turbulence, and flux in church models, it is important to remain open to reexamining our mental models of religion. What religion is and does is often far out in front from what academics conceptualize it to be. Though these numbers appear to be well beyond what people would guess, they have been replicated in multiple surveys and have been validated by analyses linking the 7M to substantive dominionist positions. The results reinforce McCrummen’s reporting, Taylor’s elite-level history of the NAR, and a growing amount of other reporting and research.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website, on Bluesky, or on Twitter.