By Brooklyn Walker

Image Credit: St-Takla.org.

It’s been less than 10 years since the concept ‘Christian nationalism’ entered the field of religion in politics, and yet a quick Google Scholar search for Christian nationalism yields thousands of results. In the slow-moving world of academia, witnessing that type of cascade is as rare as talking to a donkey (I’m looking at you, Balaam).

A nontrivial portion of the Christian nationalism literature explores its effects on various dependent variables. In each case, the authors develop an argument to explain why Christian nationalism might be correlated with opposition to interracial marriage or climate change beliefs, for example. Those arguments draw from a diverse set of theoretical frameworks, some rooted in identity, others in ideology. Due to this muddled state of affairs, scholars and critics of Christian nationalism alike have begun asking, What exactly is Christian nationalism?

Some scholars have argued that Christian nationalism is, at its root, White advocacy and supremacy. Robert P. Jones tells a story of Christian nationalism that goes back to the Doctrine of Discovery developed in the mid-to-late 1400s. In his telling, the Doctrine of Discovery institutionalized the view that the Church (and Western civilization) was superior to all other religions, races, and cultures and, consequently, had a right to rule over and guide all other peoples. According to Jones, today’s Christian nationalism carries the genetic marker of the Doctrine of Discovery.

Other scholars have defined white supremacy right into Christian nationalism. In their agenda-setting book, Whitehead and Perry say that “Christian nationalism includes assumptions of […] white supremacy.” Perry in particular has developed these ideas more fully. He argues that many Americans reject explicitly racialized messages, so it could be the case that mention of a (implicitly White) Christian nation could be an alternative mechanism for elites to dogwhistle their attitudes of White supremacy.

While some argue that Christian nationalism is basically about the power of one racial group, others say that Christian nationalism is, at its root, a broader notion of power relationships referred to as authoritarianism. Authoritarian personalities favor conformity to existing norms and push for maintenance of the status quo through obedience to authority. Philip Gorski and Samuel Perry highlight the importance of authoritarian control for Christian nationalists, and Jesse Smith argues that Christian nationalism may just be authoritarianism repackaged.

What exactly is the relationship between Christian nationalism, racial resentment, and authoritarianism? To explore this question, I turned to the 2021 General Social Survey (GSS). The GSS doesn’t have the most common scales for Christian nationalism, racial resentment, and authoritarianism. But it does have items that are pretty close, while capturing attitudes on a host of other issues. The variables I used for each concept are listed below.

Christian Nationalism

- The U.S. would be a better country if religion had less influence.[reverse coded]

- The United States Supreme Court has ruled that no state or local government may require the reading of the Lord’s Prayer or Bible verses in public schools. What are your views on this – do you approve or disapprove of the court ruling?

- The success of the United States is part of God’s plan.

- The federal government should advocate Christian values.

Racial Resentment

- Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same

- On the average (Negroes/Blacks/African-Americans) have worse jobs, income, and housing than white people. Do you think these differences are . . . Mainly due to discrimination? (reverse-coded)

- On the average (Negroes/Blacks/African-Americans) have worse jobs, income, and housing than white people. Do you think these differences are . . . Because most (Negroes/Blacks/African-Americans) just don’t have the motivation or willpower to pull themselves up?

Authoritarianism

- If you had to choose, which thing on this list would you pick as the most important for a child to learn to prepare him or her for life? Which comes next in importance? Which comes third? Which comes fourth? To think for himself or herself (reverse-coded)

- If you had to choose, which thing on this list would you pick as the most important for a child to learn to prepare him or her for life? Which comes next in importance? Which comes third? Which comes fourth? To obey

As we would expect from existing work, Christian nationalism is strongly and positively correlated with both racial resentment and authoritarianism. On a scale of 0-1, the correlation of racial resentment and Christian nationalism is 0.495, and of authoritarianism and Christian nationalism, 0.462. It’s noteworthy that the strength of these correlations is approximately equivalent.

But to what extent are these three concepts related to outcomes we political scientists might be interested in? I examined three different attitudes and included party identification, religious service attendance, education, sex, income, and White racial identification as controls. I ran four different models for each dependent variable: (1) Christian nationalism + controls, (2) racial resentment + controls, (3) authoritarianism + controls, and (4) Christian nationalism + racial resentment + authoritarianism + controls.

First, I combined three questions on the GSS about women’s roles that point to whether women should stay home to care for children while men work. Positive values show more conservative gender role attitudes. When only Christian nationalism is included, it has a positive and significant effect. Racial resentment and authoritarianism by themselves look similar–their effects are significant and positive. But once all three independent variables are included in the same model (purple dots and whiskers), only Christian nationalism retains its significance. It is doing the bulk of the work here, and excluding it would lead to the biased conclusion that racial resentment and authoritarianism predict gender attitudes.

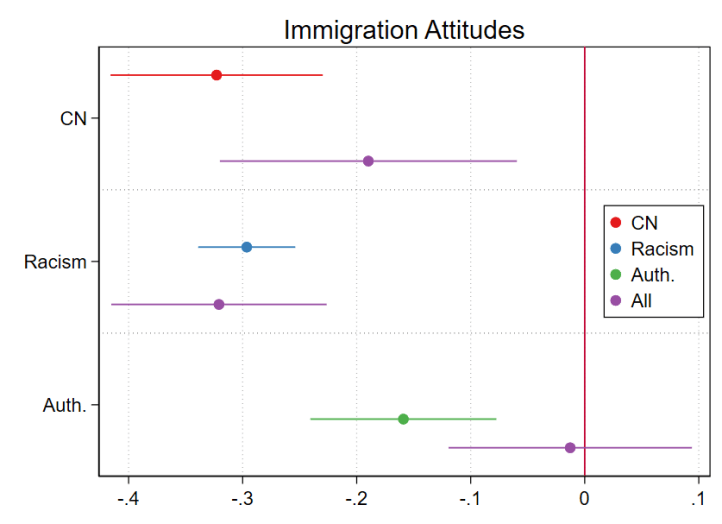

Then I turned to a GSS question about whether the US should let in more immigrants. Higher values show more support for increasing immigration quotas. By themselves, we might conclude that Christian nationalism and authoritarianism are strong predictors of opposition to immigration. But again, the effects shift once relevant covariates are added to the model. Once racial resentment is introduced (again, the purple dots and whiskers), the effect of Christian nationalism and authoritarianism diminish. This isn’t to say that Christian nationalism itself doesn’t matter when it comes to immigration–it’s clearly still negative and significant–but that some of Christian nationalism’s explanatory power is actually derived from its correlation with racial resentment.

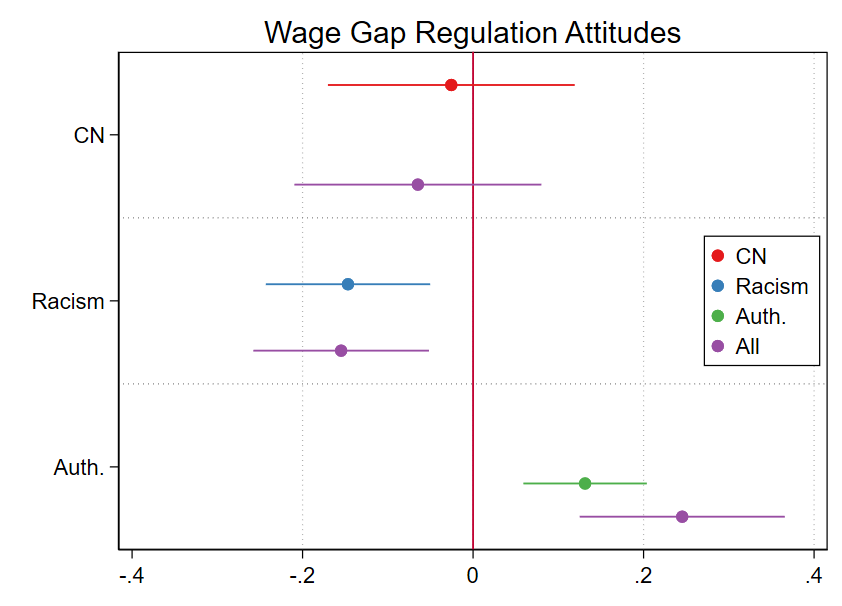

Finally, the GSS asks whether the government should take steps to limit executive pay at major companies. Christian nationalism doesn’t have a statistically-significant effect regardless of what else is included. Racial resentment is associated with decreased support for government intervention, while authoritarianism is associated with increased support.

There are several takeaways. First, Christian nationalism, racial resentment, and authoritarianism are distinct concepts. While they are correlated at moderately strong levels, they have different effects depending on the outcome under investigation. Second, because Christian nationalism is highly correlated with racial resentment and authoritarianism, and because racial resentment and authoritarianism are often correlated with the outcomes we’re interested in, it’s important that we account for racial resentment and authoritarianism when theoretically appropriate.

Finally, Christian nationalism has been conceptualized as both an identity and as a worldview. Identity-based explanations focus on the relationships between groups while ideology-based explanations focus on the ideas people hold. Correlations with racial resentment (rooted in identity) or authoritarianism (rooted in ideology) could help adjudicate between the two. This brief investigation doesn’t yield evidence that would definitely answer that question, since Christian nationalism is equivalently correlated with both and behaves, at times, like both.

Whether Christian nationalism acts as identity or worldview (or both) remains an open question. Paul Djupe, Anand Sokhey, Don Haider-Markel, and I are exploring exactly this question in a new manuscript. We asked people not just the Whitehead and Perry questions about Christian nationalism (which measure how much people support various ideas about religion in public spaces, which is a type of worldview), but also whether they identify with Christian nationalism using standard items from the identity literature. We are curious about whether this worldview and identity are correlated with each other and also whether they have similar effects. Stay tuned for those results.

Brooklyn Walker is currently an Instructor of Political Science at Hutchinson Community College but in the fall will join the University of Tennessee-Knoxville as Assistant Professor of Political Science. Her work focuses on religion and politics, public opinion, and political psychology, with a focus on Christian nationalism. To learn more, visit brooklynevannwalker.com or follow her on Twitter @brooklynevann.