Paul A. Djupe and Brooklyn Walker

Image Credit: Florida Weekly.

So much of the commentary around Christian nationalism wants to limit it, often just to Whites. Such rhetorical fencing serves to narrow the scope of the worldview and create an “other” that is politically palatable. But what if adherence to Christian nationalist attitudes extends beyond White conservative Christians into groups that logically shouldn’t support “White Christian nationalism”?

In new research out at Political Research Quarterly, we were inspired by Phyllis Schlafly and her son John. Phyllis Schlafly became a national figure in her fight against the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). She argued that the text of the ERA would empower the emerging gay rights movements, rendering same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples a constitutional right. The gay rights movement was especially problematic, in her view, because, “[t]o use the law to extend such rights to homosexuals would be a grave interference with the rights of the rest of our citizens. It would interfere with our right to have a country in which the family is recognized, protected, and encouraged as the basic unit of society.”

Phyllis is credited with stopping ERA ratification in its tracks. But to do so, she needed a network of supporters. One of the most important was Phyllis’ son, John. He provided financial services to Eagle Forum (Schlafly’s organization), attended events with his mother, and served as a leading aid. In the early 1990s, newspapers reported that John Schlafly was gay, reports that John himself did not deny. Instead, he stood steadfast in his support of his mother’s anti-LGBT activism, writing and speaking in opposition to LGBT rights.

We drew on data from three very different survey efforts from 2017 to 2023 to see if, indeed, there are LGB Christian nationalists (like John) in the US and how adherence to that worldview is linked to their politics. Though some of the measurements are different, they all tell the same basic story.

[Before proceeding, we want to note that we are examining the attitudes of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals. The only reason for that is that our data sources do not include gender identity measures (“T”). In the published article, we call for consistent measurement of gender identity sufficient to enable more inclusive analyses.]

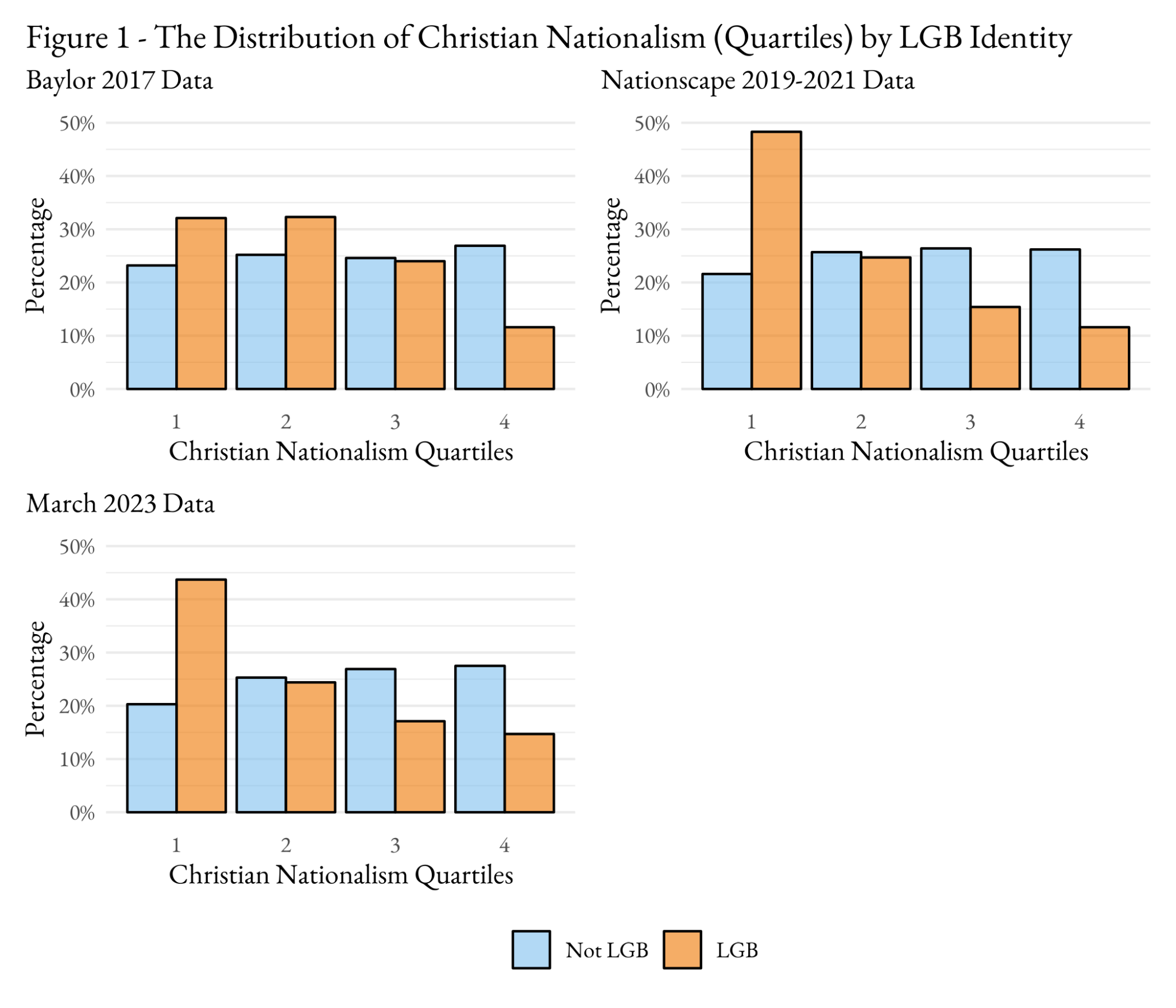

Given the anti-LGBT posture of Christian conservatives, it is hard to fathom that there are LGB Christian nationalists, but Figure 1 shows that roughly 15 percent of LGB identifiers fall into the top quartile of support for Christian nationalism. And that’s true whether using the Whitehead and Perry measure of Christian nationalism (Baylor 2017 survey and our March 2023 survey) or not (the Nationscape survey). To be sure, LGB Americans support Christian nationalism at a lower rate than non-LGB Americans, but support is not absent.

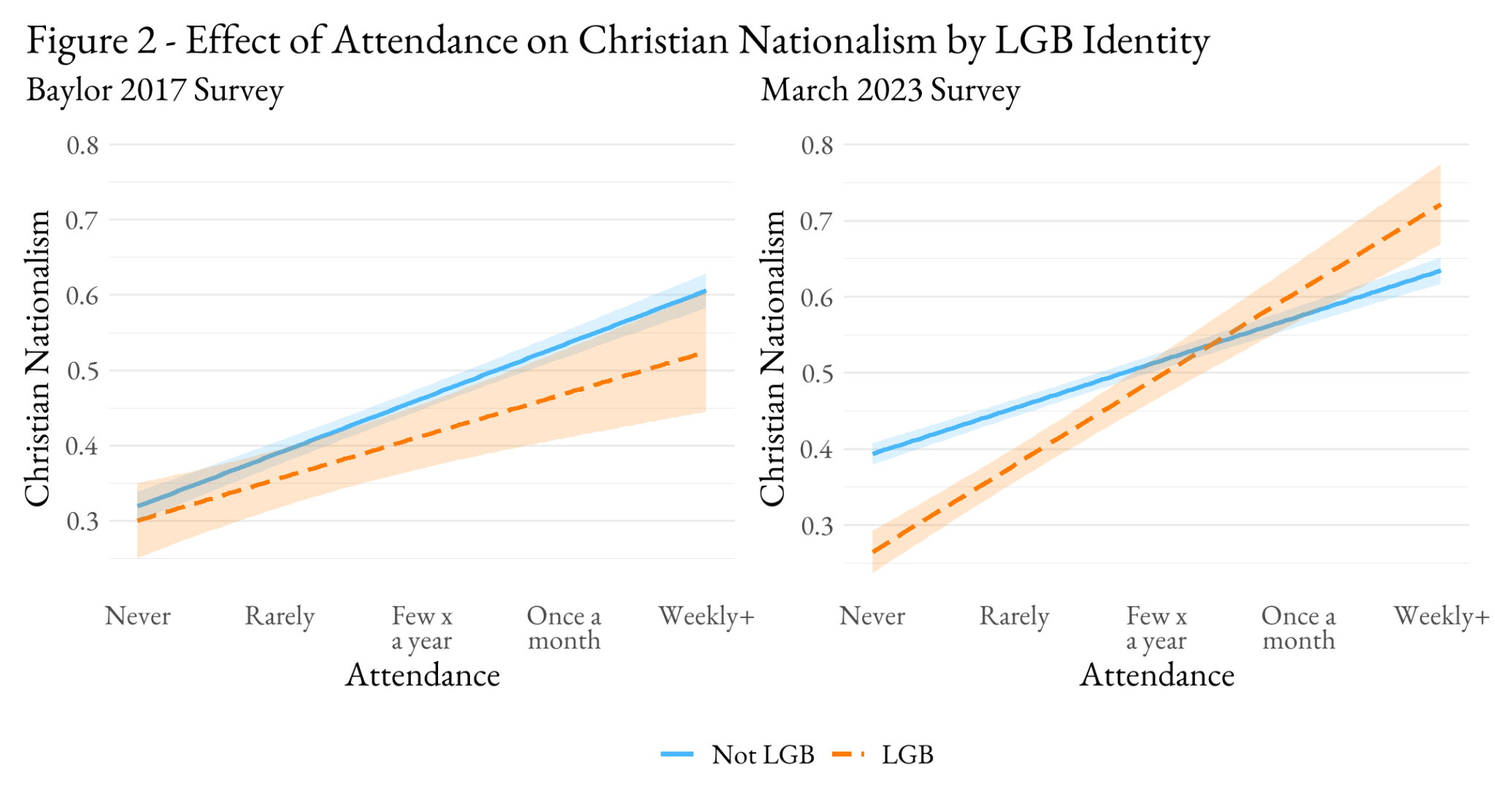

We wondered what could be responsible for these patterns and explored, among other things, perhaps the most obvious explanation – adherents of Christian nationalism simply attend worship services more often. In the Baylor data, attendance has essentially the exact same effect boosting Christian nationalism, while in our March 2023 data, attendance actually has a stronger effect on LGB Christian nationalism. But, in both cases, the relationship is positive and strong. It seems clear from these data that religious LGB Americans are not, by and large, segmented into LGB-friendly, “welcoming” congregations.

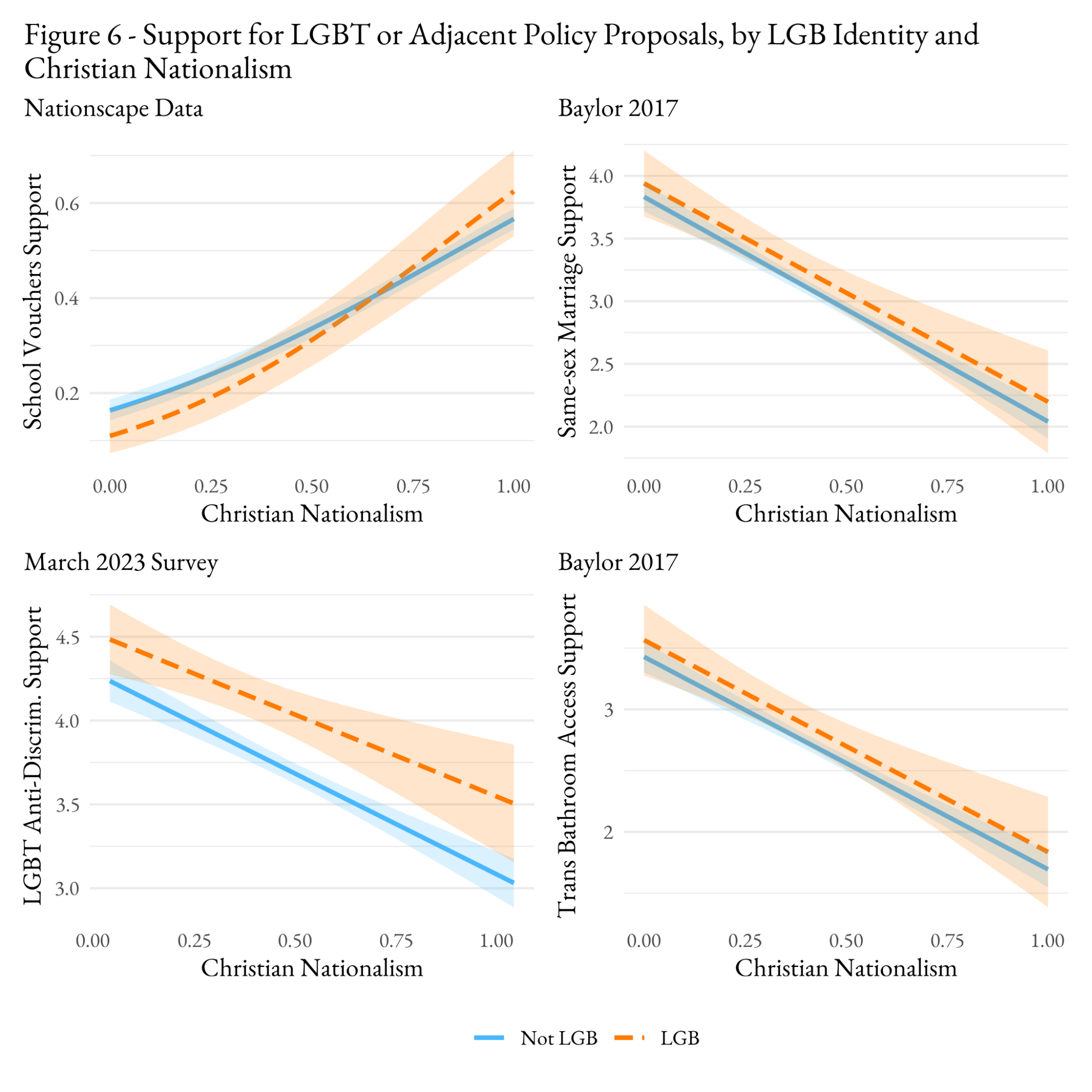

That still does not tell us if LGB and non-LGB Americans connect their worldviews to politics in the same way. We were able to pull relevant policy positions targeting LGBT rights and interests from all three datasets. Figure 6 (below) from the article shows the link between Christian nationalism and those policy positions for LGB and non-LGB Americans. The findings are not nuanced. LGB Americans have about the same level of support for these policies as non-LGB Americans, and their support shifts with their Christian nationalism adherence just as it does for non-LGB Americans. Christian nationalism is linked to greater support for private schooling, more opposition to same-sex marriage, greater opposition to LGBT anti-discrimination policies, and more opposition to trans bathroom access of their choice. The one bit of nuance is that LGB Americans are slightly more in support of anti-discrimination policies, though their support falls almost as much across the Christian nationalism spectrum.

These stunning results stand in some contrast with findings looking for group divergence in how Christian nationalism is linked to political interest. That is, others have found that Black Christian nationalists do not follow the positions of White Christian nationalists, at least when those policies would weaken their rights (think voting rights). Here, though, we find clear evidence that Christian nationalism does not observe group identity boundaries, even on concerns about fundamental rights. Why?

We suspect that the difference lies in how groups are clustered and the (perceived) immutability of group membership. LGB Christian nationalists are likely not worshipping in LGB congregations, and are likely socially isolated from other LGB identifiers. Moreover, as we show in the article, LGB Christian nationalists are also quite likely to believe that sexual orientation is a choice, just like non-LGB Christian nationalists think. Without those social and identity protections, it is perhaps not surprising that LGB Christian nationalists are bound to follow the line their religious group is taking.

LGBT Americans constituted about 7 percent of the population in 2023 according to Pew, suggesting that LGB Christian nationalists constitute about one percent of the population. While small, this means they are larger than the Muslim population and are certainly big enough to sway close elections.

Our research does not challenge the determination that Whitehead and Perry reach that Christian nationalism promotes heteronormativity, just as it is linked to antisemitism, racism, and other sharp group boundary drawing. However, we should not assume what that entails for group support in the population. That is, we can’t assume that anti-LGBT prejudice wrapped up in the Christian nationalist worldview precludes support from the targeted community. There are LGB Christian nationalists who take on policy positions that undercut the place of LGB Americans in the public sphere.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website or on Bluesky.

Brooklyn Walker is currently an Instructor of Political Science at Hutchinson Community College but in the fall will join the University of Tennessee-Knoxville as Assistant Professor of Political Science. Learn more about her work on Twitter, Bluesky, or at her website.