By Paul A. Djupe and Brooklyn Walker

316Tees, a leading purveyor of Christian clothing, offers several unisex t-shirts featuring American flags and phrases like “One Nation Under God” or “God Bless America.” Their women’s shirts reference grace, joy, love, and coffee, many in bright or pastel colors. The men’s shirt section takes a decidedly different tack. Against dark backdrops men are admonished to “Be the Warrior God Called You to Be”, be a “Hold Fast Dad: Dedicated and Devoted to Faith, Family and Freedom”, or devote themselves “For God and Country, Honor and Glory.” All of these t-shirts, at least at the time of writing, display an American flag on the sleeve, integrating ‘biblical manhood’ with violence, male headship over the family, and nationalism.

These elements are not woven together as a mere marketing ploy. In the book Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, Kristin Kobes du Mez (2020) tracks the evolution of masculinity as constructed through evangelical media and books. She argues that, since the 1950s, evangelicals have increasingly idealized men who possess militarized and armed masculinity. Du Mez goes on to assert that this militarized masculinity is central to the story of the January 6 insurrection because it asserts “the necessity of violence in pursuit of righteousness.” Her work has become central to scholarly discussions of Christian nationalism that other scholars have defined as the “set of beliefs that the nation is of, by, and for Christians.”

Indeed, Christian nationalists themselves exhort men to embrace masculinity for the sake of the Christian nation. Andrew Torba and Andrew Isker, in their Christian Nationalism: A Biblical Guide for Taking Dominion and Discipling Nations, assert that “Now it is time for our nation to be led by wise Christian warriors who fear God, read their Bible, and will not bend their knee to the wicked Establishment class and the ways of the world. In other words: we need Christian men who embrace their God-given masculine energy to conquer and lead. Currently we have weak and pathetic emasculated ‘Christian’ men who embrace submissive feminine energy. That ends now” (2022, 25). Torba encouraged the use of political violence on January 6 in posts on his social media site, Gab. In other words, true “Christian men” are socially-dominant and willing to use violence, all for the sake of the Christian nation, while holding men who fall short of these standards in contempt.

But if we were to look systematically across the population, would we find Christian nationalism to be a font of masculinity for men? We did just this in our new paper out at Sociology of Religion. We have survey evidence dating back to 2021 (3,600 adult Americans, weighted) that has the crucial elements to unravel this puzzle – perceived masculinity and femininity (asked individually using 100 point scales), a Christian nationalism measure (the Whitehead and Perry version), and some outcomes that we care about, including sexism and approval of violence in politics.

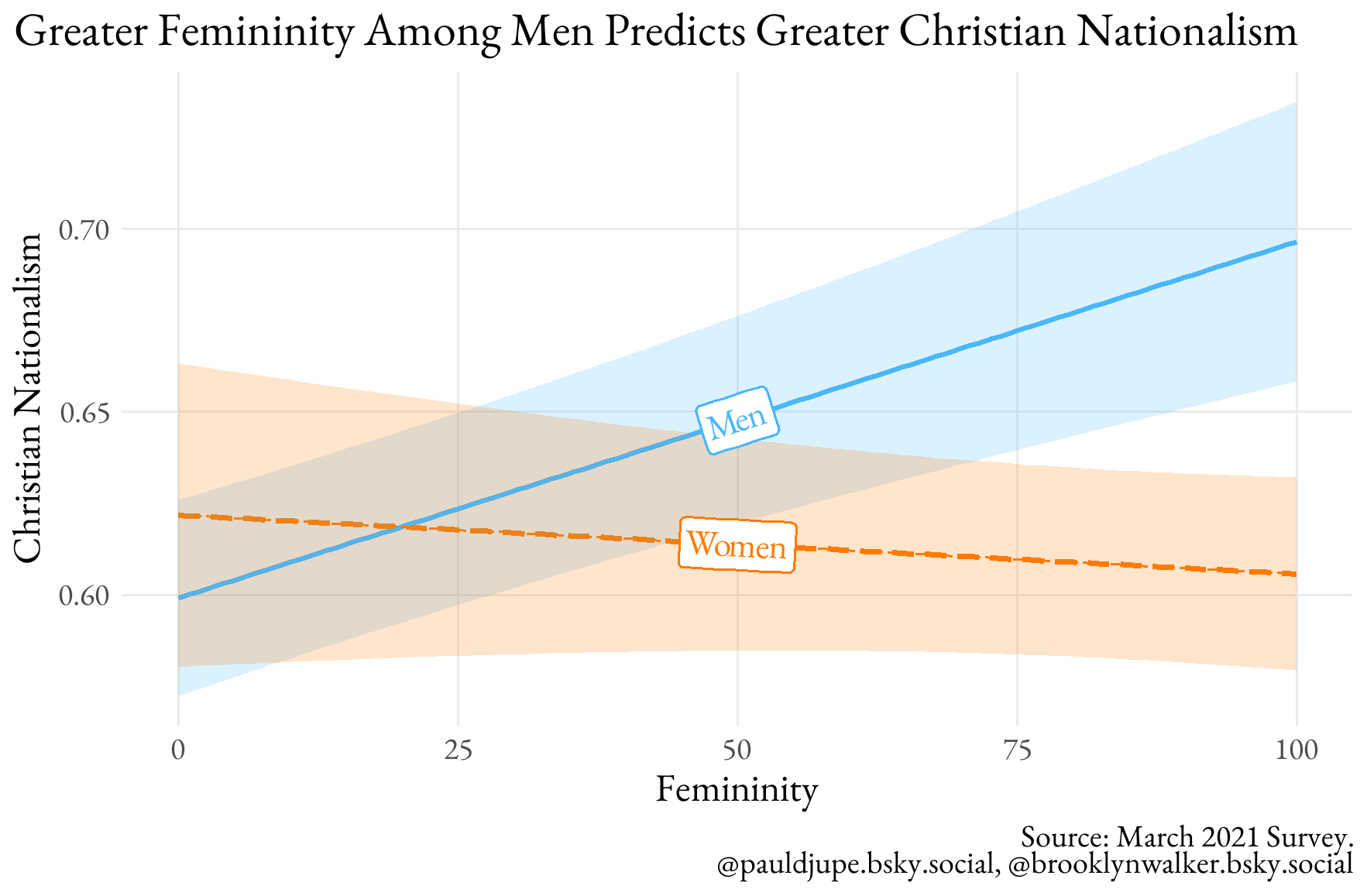

It is no surprise that women strongly identify as feminine and weakly as masculine, while the inverse is true for men. However, fully 29 percent of men score above 25 on the femininity scale – a substantial minority of men who identify as some significant degree of feminine. The key, though, is whether any Christian nationalist men identify as some measure of feminine. This is surprising: 24 percent of men in the least Christian nationalist quartile identify as some degree of feminine (25 or above) while 35 percent of men in the highest Christian nationalist quartile do. There is a steady rise of femininity scores for men across the Christian nationalism scale, which, as we can see in the figure below, holds in the presence of demographic and other controls in a statistical model. The most feminine men are 10 percentage points more Christian nationalist than those perceiving no femininity. We can also see that levels of femininity have no link to Christian nationalism for women.

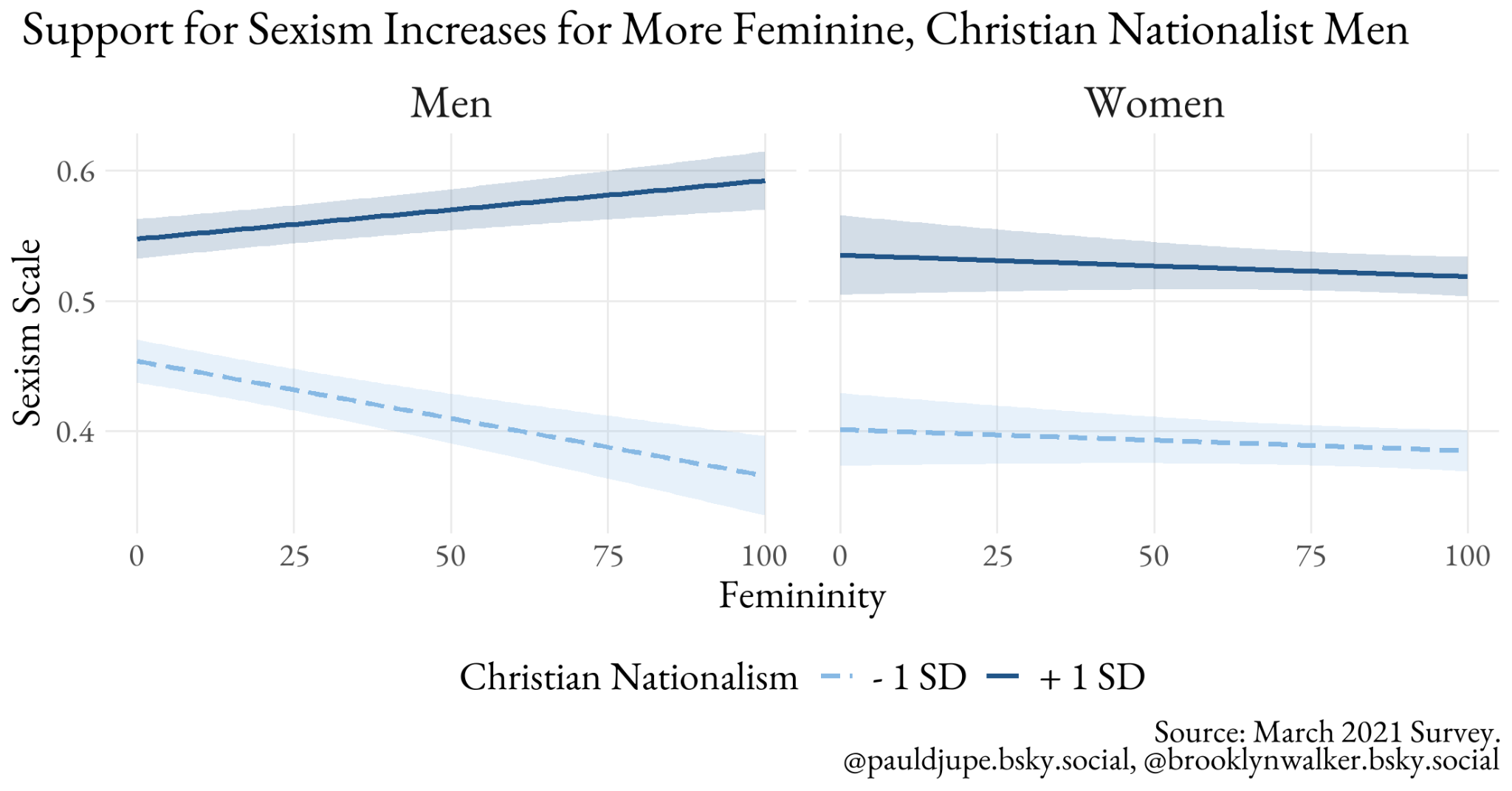

A key component to the Christian nationalist right across time, especially post World War II, is a highly patriarchal system exemplified by the glorification of figures like John Wayne. If this dynamic plays out in the data, we should see more feminine Christian nationalist men cling more tightly to a collection of sexist attitudes. And that is just what the following figure shows. For both men and women, there is a sizable gap produced by Christian nationalism (the difference between the lines). For women that is the end of the story because their femininity levels do not factor into their sexism. But, for men, greater femininity drives up sexism scores when they also hold Christian nationalist views; femininity has the opposite effect when they reject Christian nationalism, driving down sexist views.

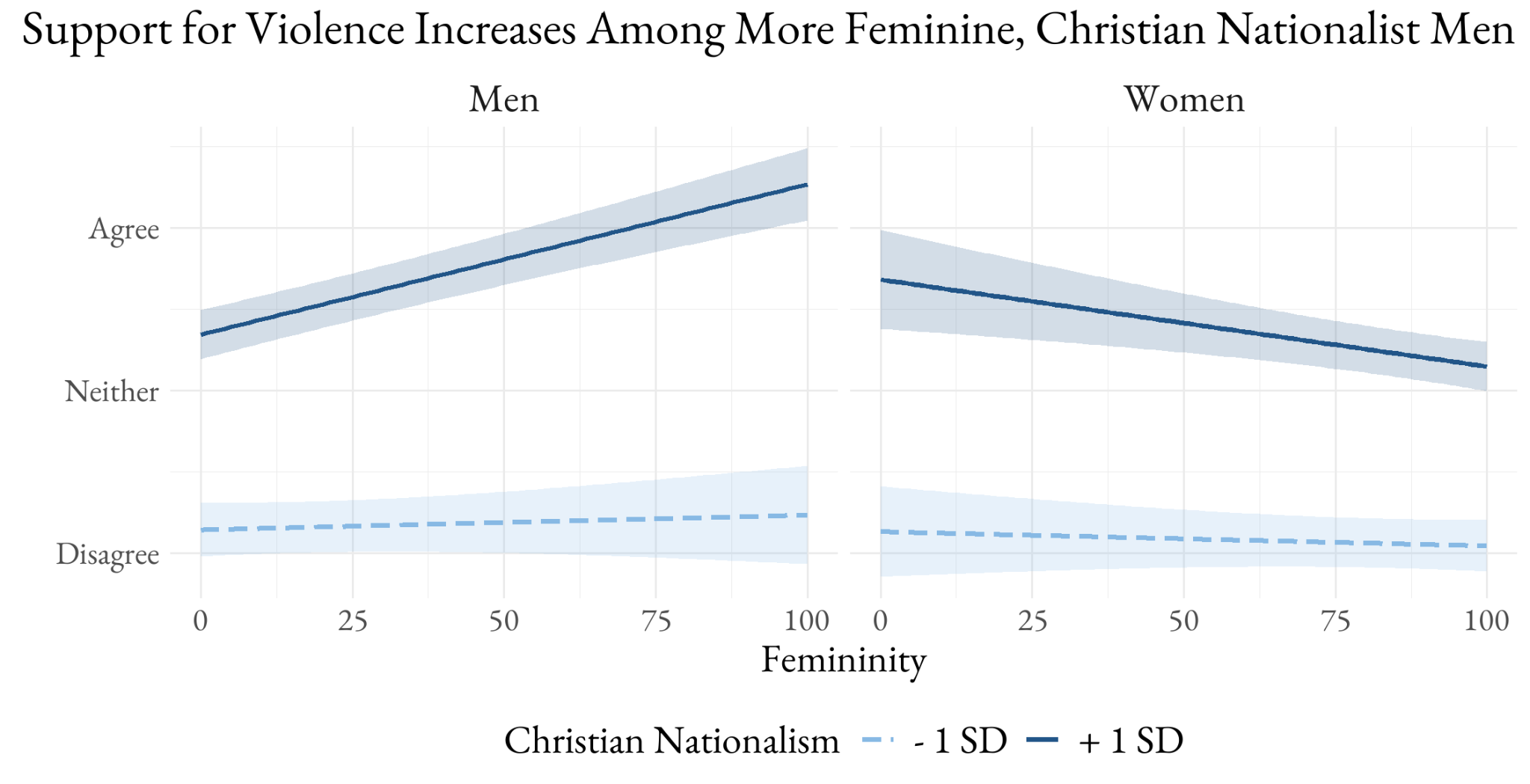

The Christian nationalist patriarchal system is based on perceived righteousness. Recognizing that this social structure is not widely shared, proponents often turn to the only force that can establish and maintain it – violence. We combined responses to two survey questions concerning the use of force: “The traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it.” and “If elected leaders will not protect America, the people must do it themselves even if it requires taking violent actions.” They place proponents squarely outside of the democratic process, implying that social change is illegitimate and must be opposed by force if necessary. The following figure shows how femininity contributes to support for violence among men – support for the use of force goes up the more that men are feminine and Christian nationalist. In this case, support for violence actually declines a bit among Christian nationalist women who are more feminine. Otherwise femininity has no effect on those outside of the Christian nationalist worldview, all of whom disagree with the use of force, on average.

As Du Mez describes, Christian nationalists have constructed a model of masculinity that valorizes social dominance and militarism. But nontrivial numbers of Christian nationalist men perceive that they fall short of this ideal. In sensing their shortcomings, they compensate by doubling down on sexist attitudes about women and a willingness to employ violence – the very characteristics that epitomize the Christian nationalist masculine ideal. This is not the only data we have that can tell this story – we have validated the findings shown above with more recent data from March 2023. That shows that these patterns are not just a function of the chaos unfolding in late 2020, early 2021 (pandemic, presidential election, insurrection, etc.). Instead, our data point to robust patterns in Christian nationalism’s ability to shape how men in particular see themselves and their place in American society.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Bluesky.

Brooklyn Walker is currently an Instructor of Political Science at Hutchinson Community College but in the fall will join the University of Tennessee-Knoxville as Assistant Professor of Political Science. Learn more about her work on Twitter, Bluesky, or at her website.