By Brooklyn Walker and Paul A. Djupe

[Image credit: Georgetown Gender + Justice Initiative]

Despite initially receiving ambivalent reactions, Roe v. Wade soon divided the country. Anti-abortion politics became a focal point for the Christian right, with evangelical leaders like Jerry Falwell proclaiming that legalized abortion marked the end of conscience and the beginning of fascism in America. The anti-abortion movement became especially active, even violent, during the 1991 “Summer of Mercy”. Even though anti-abortion activism morphed from a war for the culture to a claim of religious liberties, anti-abortion attitudes, including the drive to overturn Roe v. Wade, were a significant factor leading evangelical voters to cast their ballots for Trump in 2016.

Trump promised to place anti-abortion judges on the Supreme Court. And, in 2022’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, anti-abortion activists’ strategy seemed to pay off. The Dobbs decision formally overturned Roe v. Wade, obviating the constitutional right to abortion. Strict abortion restrictions popped up in Texas, Oklahoma, and elsewhere. Now it was pro-reproductive rights activists’ turn to panic. Protests swept the nation, and abortion rights motivated progressive voters, even in unexpected places like Kansas.

Roe v. Wade gave the Religious Right an enemy to fight. Would its demise (via the Dobbs decision) energize pro-reproductive rights sentiments? And would those sentiments manifest themselves in the most institutionalized manner possible: a constitutional amendment?

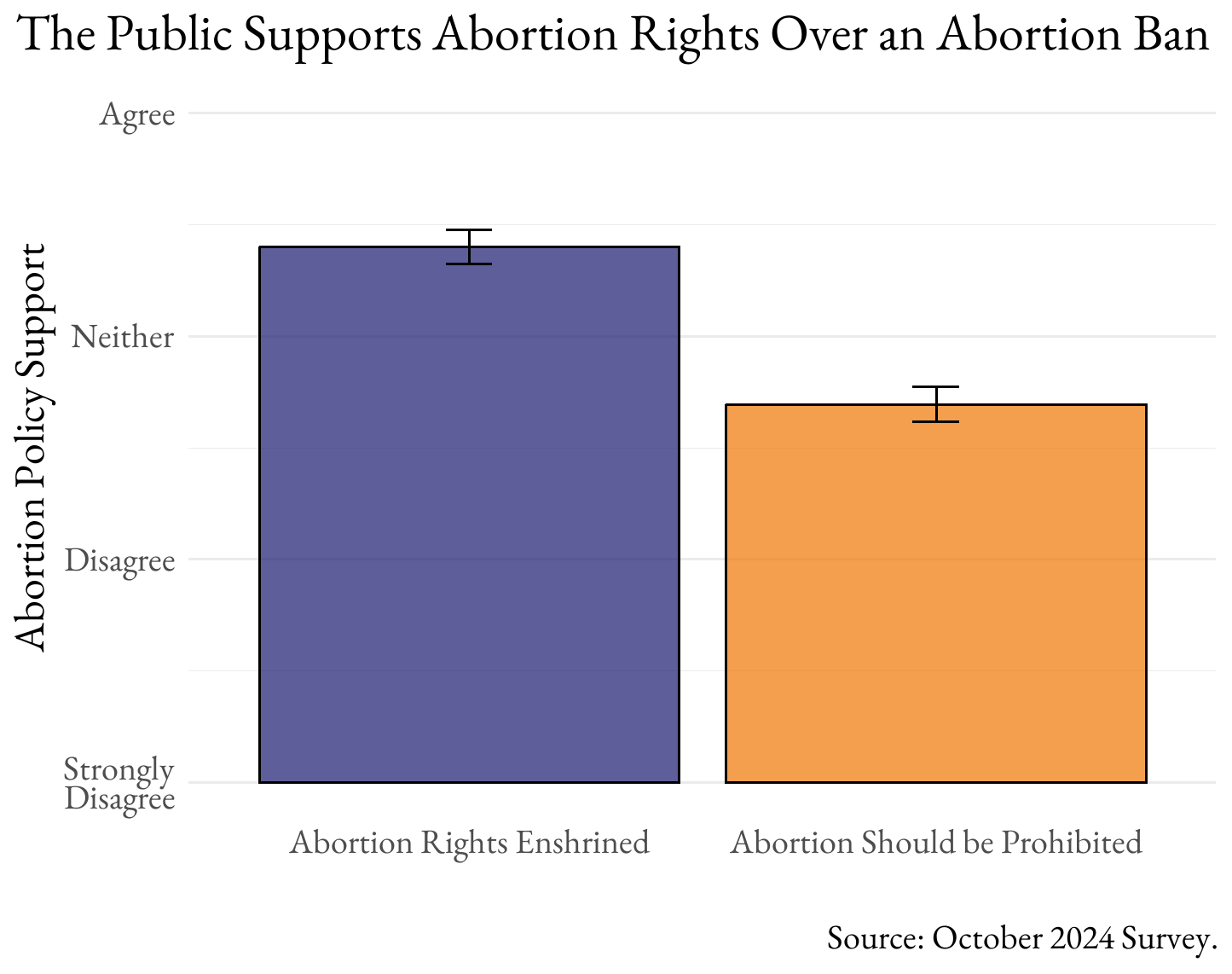

In October 2024, we fielded an experiment about abortion rights. Half of the nationally-representative sample was randomly assigned to a statement about abortion: either “Abortion should be prohibited by a Constitutional Amendment” or “The right to an abortion should be enshrined in a Constitutional Amendment”. Respondents then indicated, on a five-point scale, how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

Overall, the public slightly leans towards agreeing with abortion right protections, and leans towards disagreeing with abortion prohibition (in approximately equivalent degrees). Neither of these statements elicited particularly strong reactions.

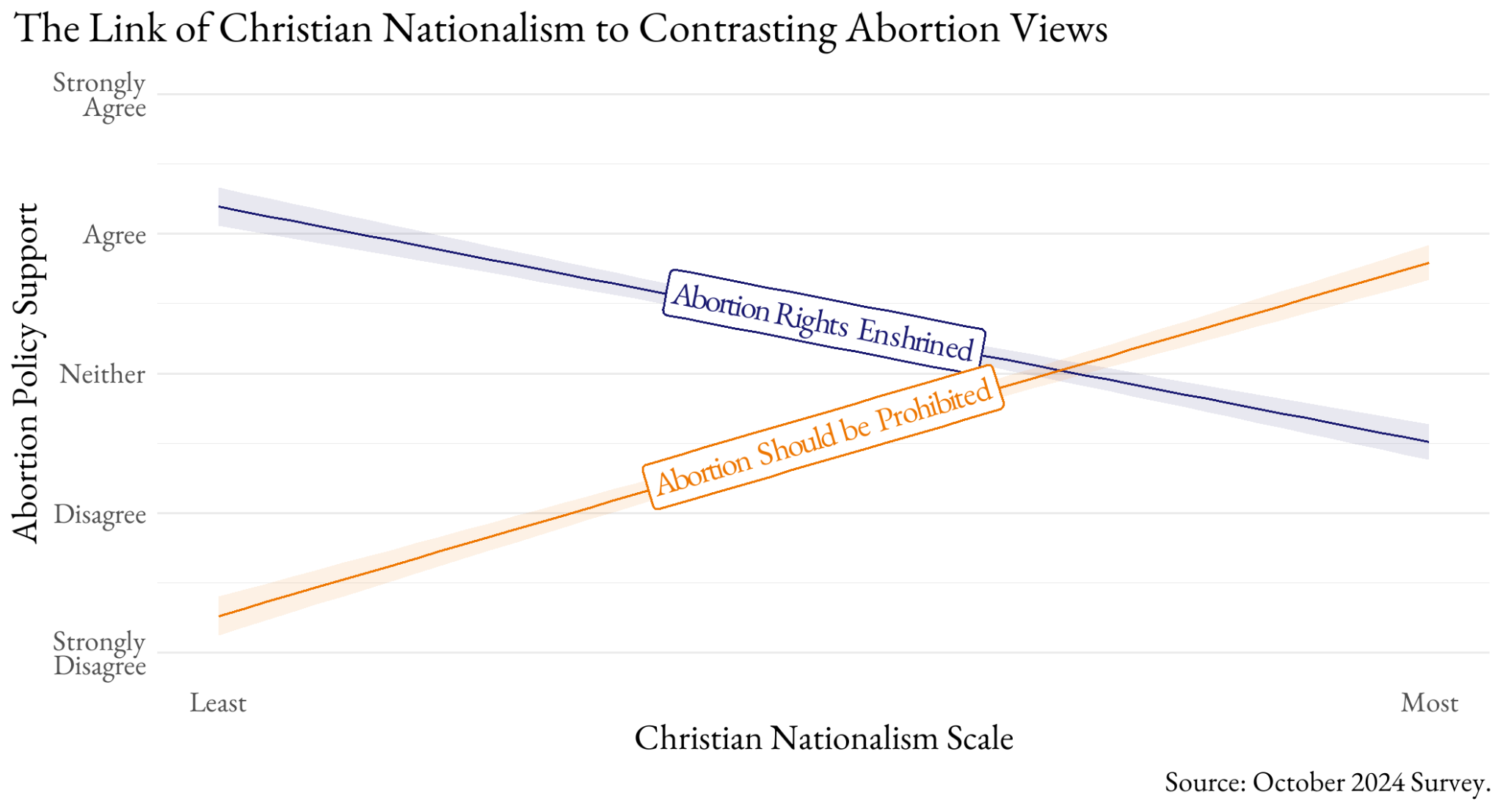

But what we were ultimately interested in is the role Christian nationalism might play. After all, Christian nationalism promotes the formal union of religion and politics, including declaring the United States to be a Christian nation and marking public spaces with Christian symbols. Surely, we assumed, individuals high in Christian nationalism who have been fighting for constitutional abortion prohibitions for decades would strongly support such an amendment (and, conversely, strongly oppose an amendment to protect abortion rights).

And that’s only sort of what we found (see the figure below). Individuals high in Christian nationalism agreed with the idea of an amendment to ban abortion. When it came to an amendment to protect abortion rights, strong Christian nationalists fell somewhere between “Neither agree nor disagree” and “Disagree”.

The most interesting part of the story, though, features the opponents to Christian nationalism (left side of the figure). Their support for an amendment to protect abortion rights falls somewhere between ‘Agree’ and ‘Strongly Agree’, and their opposition to a ban on abortion is very near ‘Strongly disagree’.

For decades now, we have thought of abortion as an animating force among those who want to ‘restore the nation to its Christian roots’. And it is certainly the case that individuals with strong Christian nationalist tendencies are more supportive of a constitutional amendment to ban abortion than they are a constitutional amendment to protect abortion rights. But the sentiments of the Christian nationalists is milquetoast compared to those of Americans who reject Christian nationalism. Among them, opposition to a constitutional ban and support for constitutional protection of abortion rights are strongly-held views.

We suspect that, without the enemy of Roe and saddled with the numerous complications that arise from abortion bans, even Christian nationalists may find themselves moderating their abortion stance. But the deprivation of rights can be a powerful motivator in general, and the Dobbs decision has illustrated to many Americans the tenuousness of abortion rights, making individuals already predisposed to be leery of Christian nationalist political projects even more so.

Brooklyn Walker is currently an Instructor of Political Science at Hutchinson Community College but in the fall will join the University of Tennessee-Knoxville as Assistant Professor of Political Science. Learn more about her work on Twitter, Bluesky, or at her website.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website or on Bluesky.