By Paul A. Djupe and Jacob R. Neiheisel

[Image credit: earth.org]

Ahead of the 2023 UN Climate Change Conference in Dubai, nearly 30 religious leaders across a wide range of faith communities gathered to pen a statement pledging to “Actively participate in public discourse on environmental matters, guiding our congregations and institutions to foster resilient and just communities.” We have some evidence about whether environmental problems are engaged in houses of worship, but we know surprisingly little about whether clergy and congregations are engaging environmental concerns in their communities. There are smartly conducted community studies, especially in European nations, but there simply isn’t in the way of analyses of religion across the population of communities anywhere, including in the US.

In our newly published research at Sociological Focus, we look for this evidence with the aid of two tremendous datasets. One is the National Study of Religious Leaders (by Mark Chaves) that asked a national sample of clergy and congregations whether they engaged with two environmental issues and engaged in environmental actions. We were able to link those data to the “Environmental Justice Index” produced by the federal Centers for Disease Control and more specifically from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. The data are still available, per a Court order but with a wild disclaimer. The EJI “ranks each [Census] tract on 36 environmental, social, and health factors and groups them into three overarching modules and ten different domains.” It’s a very useful dataset.

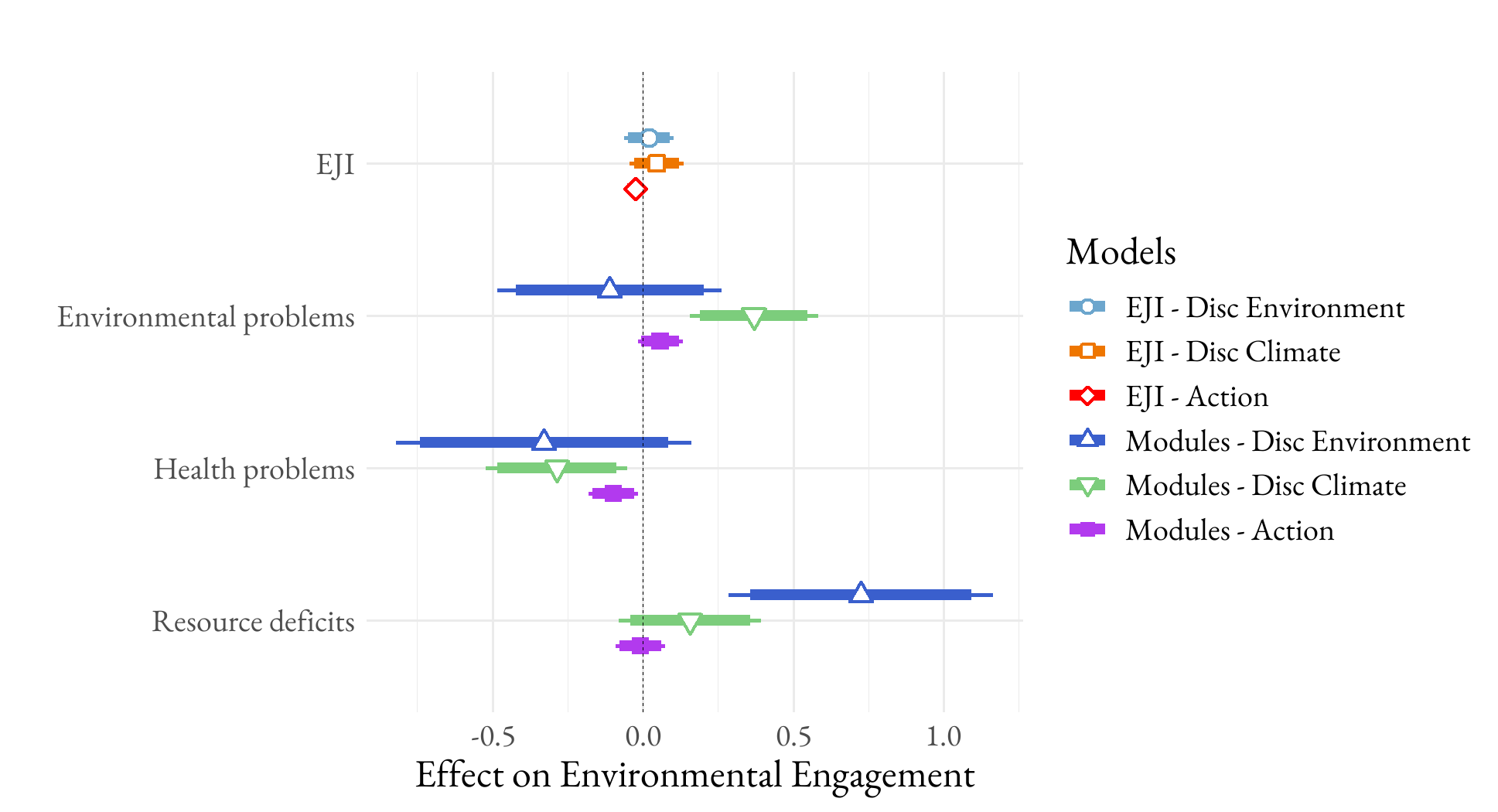

Is there a relationship between measures of local environmental conditions and engagement with the environment by religious leaders? Figure 1 shows results from a population-level set of analyses – the rows are the EJI itself and then the three components of the index. There are no relationships with the overall environmental justice index (EJI), in part because relationships between index component modules and engagement are working at cross purposes – some increase environmental engagement and some decrease it. Our key measure of actual environmental problems is linked to more discussion of climate change and a tiny bit more environmental action by the congregation (it is important to point out that we don’t know anything about the content of their public talk or the congregational action – it could be pro or anti-environmental). However, these small relationships disappear when we add sensible statistical controls about the congregation and community.

Figure 1 – Relationships between environmental measures and religious leader environmental engagement (all bivariate)

Note: Thicker lines indicate 90% CIs, while the thinner lines represent 95% CIs.

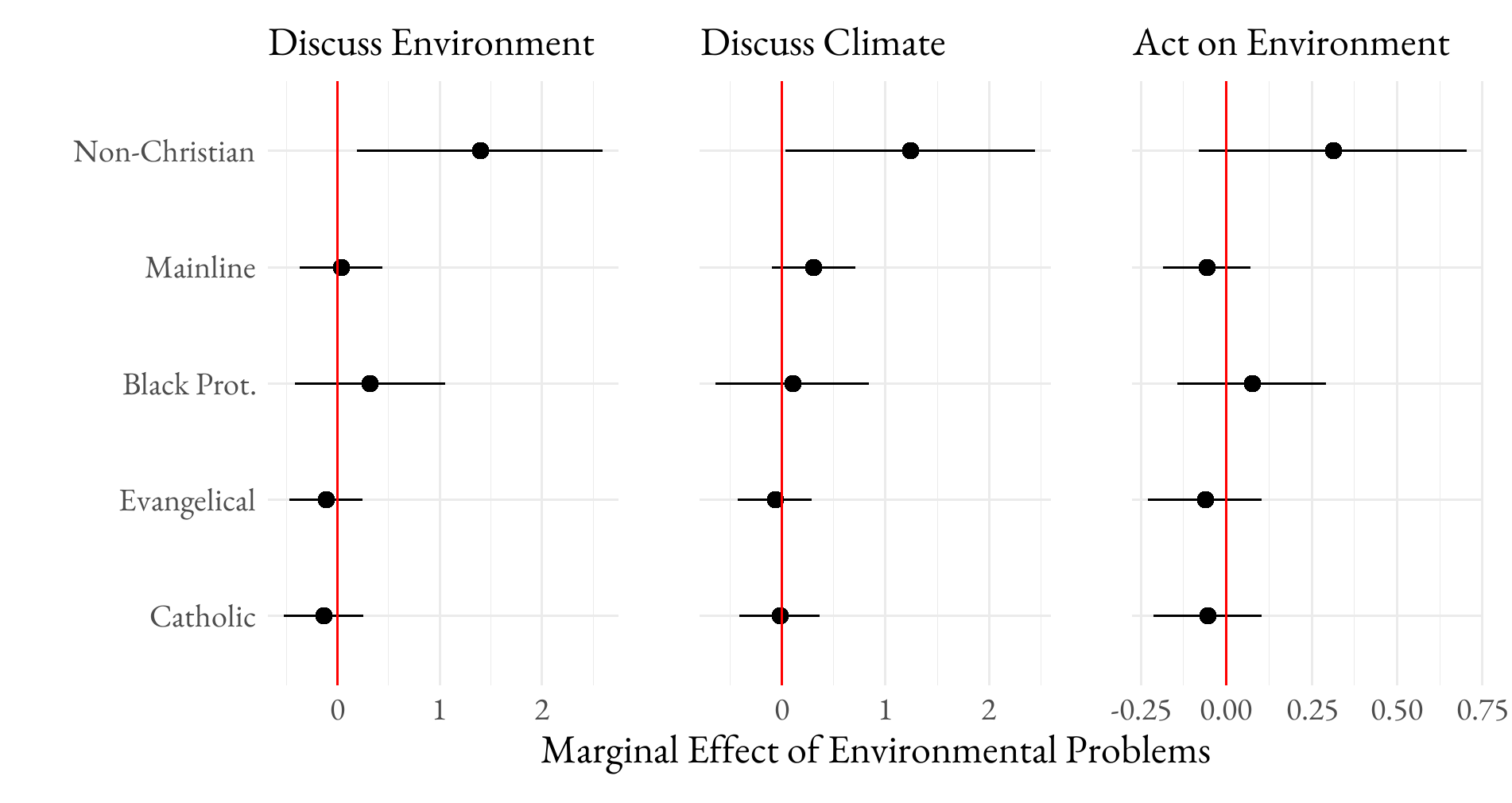

We suspected that environmental engagement would be contingent and first looked to see if more worldly, socially engaged religious traditions were more involved with environmental politics. We found almost no relationships at all between environmental problems and the three engagement variables except among non-Christians. They talked about climate and environmental science more when facing more environmental problems. That doesn’t mean Christians are uninvolved with environmental problems, but it does mean engagement is not structured by religious tradition.

Figure 3 – Estimated Effect of Religious Tradition Interactions with Exposure to Environmental Problems on Environmental Engagement

One of the sensible reasons why clergy might not engage with the environment is that it has become politically charged and they have to choose their battles when they disagree with their congregations. That’s not quite what we see in Figure 5 (disagreement is captured by the perceived partisan difference between the clergy and congregation). Disagreement has no effect on clergy discussion of the environment, but does drive down congregational environmental action. We’ve seen this sort of pattern before, where clergy motivation can get an issue on the agenda though they may temper its presentation by offering arguments on both sides. Disagreement may be more dangerous surrounding congregational action. Clergy have less control over the message when members are encouraged to take action, which could inflame political division in the congregation.

Figure 5 – Estimated Effect on Environmental Engagement of Environmental Problems Conditional on Clergy-Congregation Disagreement

Note: 95% CIs shown. Full model results are available in Table A6.

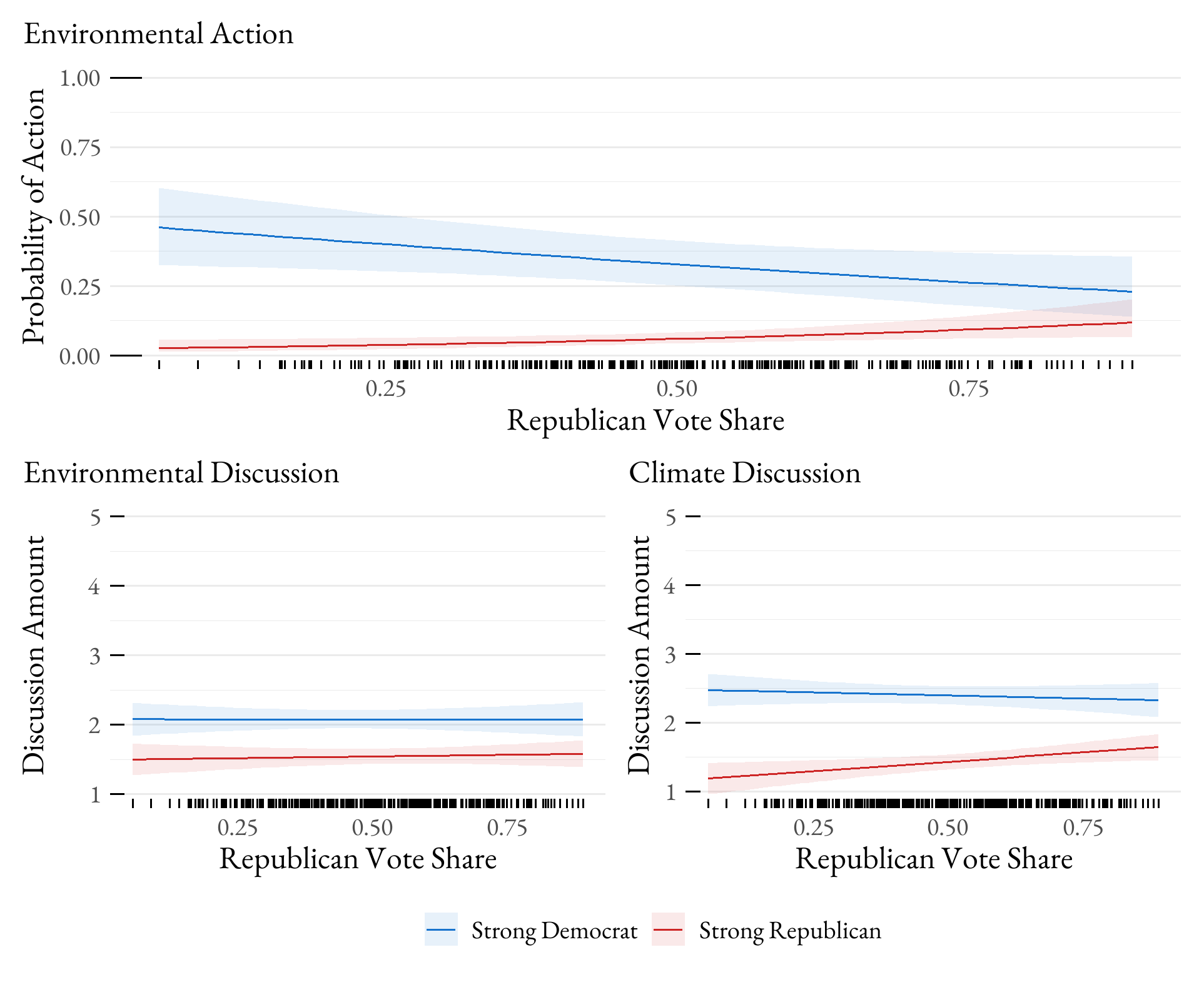

The politics surrounding clergy are important in another way. We’ve long argued that researchers pay too little attention to the influence of the broader community on what are assumed to be congregation-level dynamics. Here we have a concrete example of how that works. Strong partisans are much more likely to report congregational environmental action when surrounded by co-partisans. That probability jumps from 25 percent to 50 for strong Democrats and from essentially zero to 12 percent among strong Republicans. Exactly what mechanism is operating here is opaque, but we strongly suspect that it involves other organizations that loop in clergy and their congregations to take action. Of course, partisan agreement may also just signal social permission to take action. And, again, this measure of the social context has little effect on clergy speech patterns.

Figure 6 – Engaging the Environment Responds to Community Partisanship, but Clergy Respond Less Strongly to the Partisan Nature of their Community in their Environmental Discussion Rates

It is not surprising, perhaps, that American congregations are not uniformly engaged with local problems, especially environmental ones. But it’s worth noting the implicit assumption of most social scientific work on congregations that they are or should be concerned with what bears on the livelihoods of their congregants. Our contribution here is to show how tenuous this link is and that it depends considerably on the whims and interests of the clergy. If they want to talk about it, they will. If they want to take action, it really depends on whether there is existing support for doing so. And that means that there are serious brakes on the prophetic witness of religion.

This article is part of a special issue that we co-edited about Religion and Politics in American Congregations that will be published in July 2025. It has a tremendous collection of new research, listed below, that you should check out if you work in this area. We’ll add URLs and pub details as they come online.

Beyerlein, Kraig and Manuel Rodriguez. 2025. “The Effect of Congregational Context on Religious Leaders’ Political Activism.” Sociological Focus. 58(3).

Mrchkovska, Nela, and Enrique Quezada-Llanes. 2025. “Voices from the Pulpit: Discourse on Racial Justice and Gun Violence from American Clergy.” Sociological Focus, June, 1–21. doi:10.1080/00380237.2025.2516814.

Holleman, Anna, Erin F. Johnston, and Kelsey Mischke. 2025. “Walking the Tightrope: How White United Methodist Clergy Approach Race and Racial Justice.” Sociological Focus, June, 1–20. doi:10.1080/00380237.2025.2514009.

Sellers, Kathleen, and Joseph Roso. 2025. “Priestly Politics: Faith Formation and Political Ideology Among Catholic Clergy.” Sociological Focus, June, 1–21. doi:10.1080/00380237.2025.2511609.

Gilliland, Claire Chipman, Haley Shadburn, and Sabrina Strickland-Harris. 2025. “Politics, Protest, and Police: Assessing Religious Leaders’ Responses to Racism and the June 2020 Black Lives Matter Protests.” Sociological Focus, 58(3). doi:10.1080/00380237.2025.2511602.

Beckman, Diane and Evan Stewart. 2025. “Clergy Talk: Do Catholic Priests Discuss Immigration?” Sociological Focus 58(3).

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Bluesky.

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of political science and faculty affiliate with the philosophy, politics, and economics program at the University at Buffalo, SUNY.