By Paul A. Djupe, Amanda J. Friesen, Anand E. Sokhey, and Jacob R. Neiheisel

In new research out at Political Behavior (open access!), we investigate whether attending church encourages greater acceptance of atheists. If you think that statistical result is bonkers, you’re not alone – we do, too. But it turns out that scrutinizing and understanding what produces statistical results like these is important for making sure we “get it right” when it comes to understanding religious, political, and social dynamics.

The path to examining this relationship ran through our efforts to chase down another implausible set of findings in the rapidly expanding work on Christian nationalism. In that literature scholars regularly conclude that while adherence to Christian nationalism indicates more conservative, often anti-social preferences (harsher policy, separating immigrant children from their parents, etc.), higher levels of worship attendance promote the opposite: more liberal policy stands.

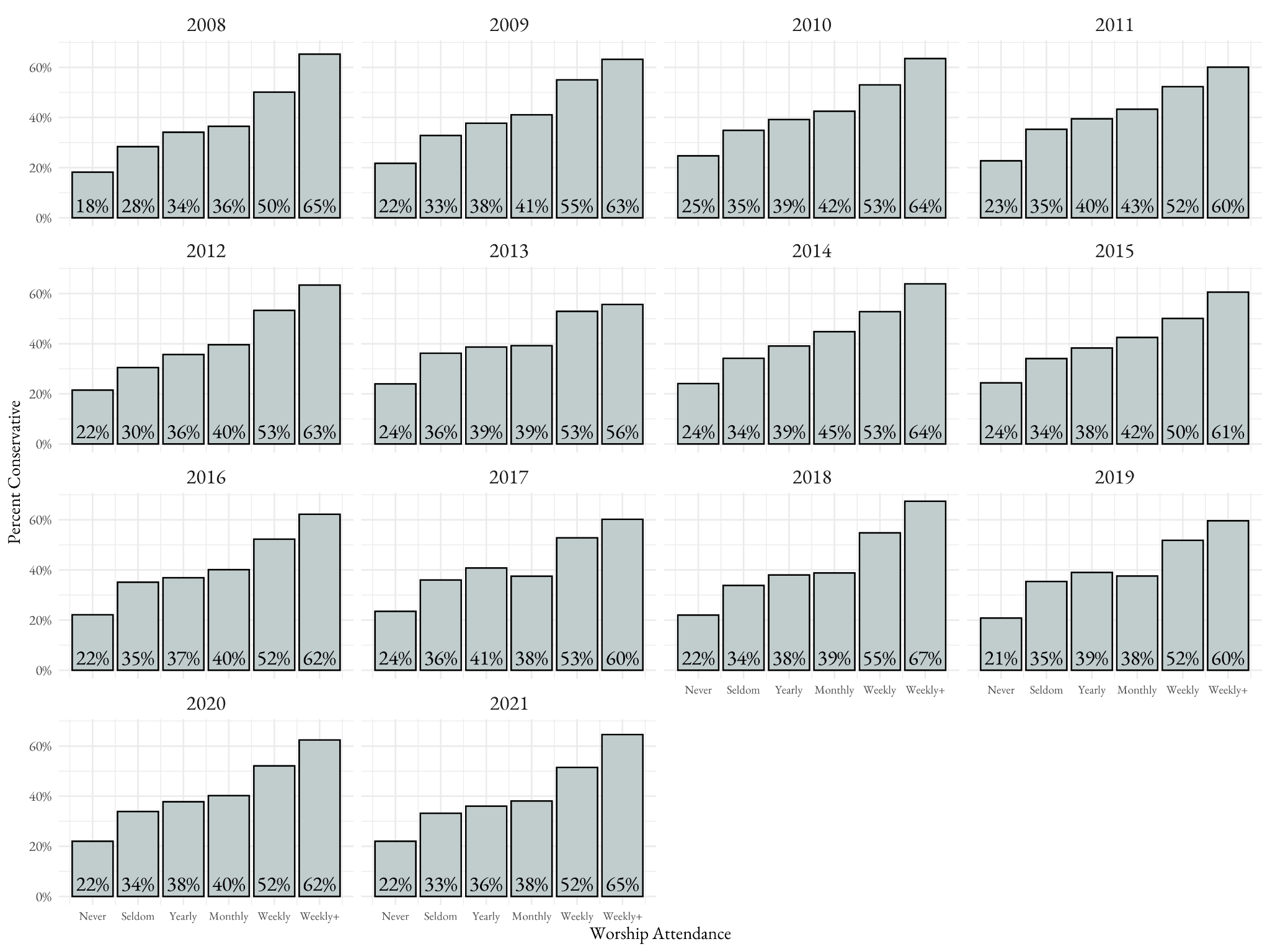

As a group of seasoned religion and politics scholars, this struck us as implausible; practically every correlation we have observed pairs more attendance with more conservative identification and policy stances. Take for instance the following evidence (from the Cooperative Election Study, 2008-2021) that shows a strong and incredibly consistent relationship between conservative identification and worship attendance (see figure below). We also found supporting evidence from a widespread look at public policies – we found no bivariate correlations linking more frequent worship attendance to more liberal stances.

Given these findings, how could we get to a place where worship attendance predicts liberalism? We were able to generate a finding connecting worship attenders to support for atheists by following a standard procedure in multivariate statistical analysis: we simply “controlled” for a wide variety of other variables that could potentially explain an outcome of interest. In some cases when these controls are highly correlated – as are Christian nationalism and worship attendance – including both in a statistical model will reduce the power of one variable, and may even reverse the direction of an estimated relationship. That is, while attendance by itself indicates less support for atheists, when we include the Christian nationalism scale in a model we find that the effect of the attendance variable doesn’t just get weaker, it flips its sign to suggest more support for atheists.

When one of the variables gets weaker in the presence of a stronger variable the dynamic is called a “suppression effect”; it’s called a “negative suppression effect” when the variable flips signs (e.g., from positive to negative). Suppression is a well-known phenomenon, with research about it dating back nearly 100 years. One recent examination of articles in a top political science journal by Lenz and Sahn suggested that about a third of published research relied on a suppression effect without acknowledging its possibility.

The only way out of this statistical quandary – is an effect “real” or is it a statistical artifact? – is by giving a good reason (and ideally some supporting evidence) that applies narrowly to an outcome of interest.

What we believe is a negative suppression effect has been a common pattern in research about Christian nationalism and immigration attitudes. As one example of dozens, Samuel Stroope and his colleagues at Baylor offer a reason why we might find that worship attenders are more liberal on immigration, while Christian nationalists are more conservative:

“When Christian nationalists are not embedded in religious communities in which expressions of love for one’s neighbor and stories of grace and redemption are shared, they may more easily drift into unvarnished advocacy of ‘culturized religion,’ populism, and a punitive nativism” (2021: 3).

In other words, the idea here is that religious involvement instills norms of love and redemption that constrain Christian nationalism.

In our analyses we pursued multiple tacks to show that such a relationship is more illusory than real – that it’s a suppression effect. We checked the attendance effect in models of attitudes about a variety of groups and individuals that did not vs did contain Christian nationalism, which can be seen below (Figure 5 from our forthcoming Political Behavior article). The top row patterns look almost identical – the estimated effect of attendance hovers around zero without Christian nationalism in the model (blue, orange, and green), but when it is in the model (red and purple) the estimates jump significantly in a direction that indicates more support for immigrants, Muslims, and atheists. We can see the same pattern on the second row when looking at political figures, too. For the conservative objects (Trump and January 6th insurrectionists), the effect starts very positive and then shrinks toward zero when Christian nationalism is added to the model.

Figure 5 – The Estimated Attendance Effect on Group/Figure Feelings is a Function of Model Specification

Source: March 2021 Survey.

As we argue in the paper,

“We suppose it is possible to construct a religion-wide story about how Christian houses of worship encourage grace and redemption about immigrants, but assuming the same dynamic for the case of Muslims seems questionable. And, we can find no plausible explanation besides suppression for the results in the upper right panel – they would suggest that the way to encourage more acceptance of atheists, often one of the most disliked groups in the U.S…, is for people to attend church more often.”

In order for us to believe that worship attendance tends to make people more supportive of liberal policies, we need to see that houses of worship are providing the supporting mechanisms for that relationship. For instance, it would be helpful to see evidence that clergy and others are talking about the plight of immigrants in a supportive way. One fairly recent look presented evidence that only a small minority of religious identifiers heard their clergy addressing immigration in the Trump I administration (see the figure below); older research has found clergy engaging in quite diverse argumentation about immigration, both in support and in opposition. That’s two points in favor of a suppression effect conclusion here. That is, we need more than a logical argument that something is possible – we need to see patterns in the data that would support a counterintuitive position. Moreover, we would argue that the logic should apply narrowly to what communication specifically addresses in houses of worship; it should not apply broadly in the same ways across groups and policies (which is what we find).

Perceived Communication of Clergy Across Three Christian Traditions, 2016-2018

Note: E=evangelical, M=Mainline, C=Catholic.

So where do we go from here? Researchers need to continue to pursue data about communication in religious bodies. In the meantime, scholars working in religion and politics need to stop making unqualified conclusions about worship attendance in the presence of Christian nationalism. More generally, all scholars of public opinion (including us!) need to exercise caution about suppression dynamics. In sample after sample worship attenders tell us they are conservatives, think like conservatives, and behave like conservatives. If statistical model results run counter to that overwhelming evidence, researchers better have really good reasons and strong supportive evidence to back their claims about such relationships. So far we haven’t seen the research community making convincing claims.

The new paper is a collaborative effort between Paul A. Djupe, Amanda J. Friesen, Andrew R. Lewis, Anand E. Sokhey, Jacob R. Neiheisel, Zachary D. Broeren, and Ryan P. Burge.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Bluesky.

Amanda Friesen is the Canada Research Chair in Political Psychology, associate professor of political science at the University of Western Ontario, director of The Body Politics Lab, and associate editor at Political Psychology. More information about her work and lab can be found here and on Bluesky.

Anand Edward Sokhey is a professor of political science and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Behavioral Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is the coauthor of several books, including a study of academic productivity in sociology and political science: The Knowledge Polity: Teaching and Research in the Social Sciences.

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of political science and faculty affiliate with the philosophy, politics, and economics program at the University at Buffalo, SUNY.