Elizabeth Oldmixon, University of North Texas

Photo credit: me [1]

On February 3, 2017, the United States Department of Agriculture released a statement indicating that animal welfare data collected in relation to the Animal Welfare Act and Horse Protection Act would no longer be publicly available. In the future, interested parties will need to make a FOIA request to access the information. With that, the agency “removed inspection reports and other information from its website about the treatment of animals at thousands of research laboratories, zoos, dog breeding operations and other facilities.” PETA condemned the move, but as the Washington Post reports, certain business interests clearly benefit from the diminished regulatory burden.

On February 3, 2017, the United States Department of Agriculture released a statement indicating that animal welfare data collected in relation to the Animal Welfare Act and Horse Protection Act would no longer be publicly available. In the future, interested parties will need to make a FOIA request to access the information. With that, the agency “removed inspection reports and other information from its website about the treatment of animals at thousands of research laboratories, zoos, dog breeding operations and other facilities.” PETA condemned the move, but as the Washington Post reports, certain business interests clearly benefit from the diminished regulatory burden.

The business versus animal activist cleavage is about what you would expect here, but there is also a religious dimension to animal welfare policymaking, which I investigate in a forthcoming article in Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Religionists who study legislative policymaking often focus on so-called culture war issues such as school prayer, LGBTQ rights, and reproductive policy (but see exceptions related to economic policy, human rights, and foreign policy). This is in part because culture war issues were championed by white evangelicals at the time of their “wholly unexpected … political resurgence … in the late 1970s.”

Religionists consistently find that religious identities and constituencies structure legislative behavior. These are important and interesting findings.[2] But given their salience—given the priority evangelicals gave these issues when they joined the Republican Party—culture war issues have well-worn partisan and religious frames. We know, however, that religious politics extends beyond evangelical politics, and evangelical politics extends beyond the culture wars. Indeed, the social connections and beliefs associated with religion provide the faithful with a fairly comprehensive worldview.

Assuming that legislators bring their personal values to bear on the policy process, the imprint of religion should be observable well beyond the usual suspects. The challenge for religionists, then, is to investigate lower salience issues, so as to develop a more complete picture of religious thinking and politics. A finding that religion affects legislative behavior on issues that lack entrenched partisan and religious frames would suggest that religion’s influence is more widely diffused than the scholarly community generally recognizes.

The crux of the theoretical argument is that legislators bring their personal religious values to bear on policy decisions. Kingdon characterizes legislative voting as a sequential process wherein legislators weigh environmental cues. Under the right circumstances—when the issue is low salience, when policy goals are implicated, when a president of the same party is indifferent—legislators can vote in accordance with their policy goals. Legislators can engage in what Barry Burden calls “personal representation,” acting on their personal religious values, while balancing external influences, such as political and economic factors. Animal welfare is just such a low salience issue. The Catholic Church and the Southern Baptist Convention have both issued documents on animal welfare, but it is nowhere near the top of the political agenda.[3] In order to suss this out, I analyzed Humane Society Legislative Fund (HSLF) animal welfare scores for U.S. senators from the 109th to the 113th Congress (2005-2014).[4] Scores reflect percent support for the HSLF’s legislative agenda. Over the 10-year period considered in the analysis, mean animal welfare scores fluctuated between 35% and 51%. The figure above provides the predicted level of animal welfare support by a senator’s religion and party. Across religious groups, Democratic support is higher than Republican support. Predictable and consistent religious differences also emerge. Among Republicans and Democrats alike, LDS Senators are the least supportive of animal welfare, while Jewish senators are the most supportive. Catholic and Black Protestant support is in the middle and nearly identical.[5]

In order to suss this out, I analyzed Humane Society Legislative Fund (HSLF) animal welfare scores for U.S. senators from the 109th to the 113th Congress (2005-2014).[4] Scores reflect percent support for the HSLF’s legislative agenda. Over the 10-year period considered in the analysis, mean animal welfare scores fluctuated between 35% and 51%. The figure above provides the predicted level of animal welfare support by a senator’s religion and party. Across religious groups, Democratic support is higher than Republican support. Predictable and consistent religious differences also emerge. Among Republicans and Democrats alike, LDS Senators are the least supportive of animal welfare, while Jewish senators are the most supportive. Catholic and Black Protestant support is in the middle and nearly identical.[5]

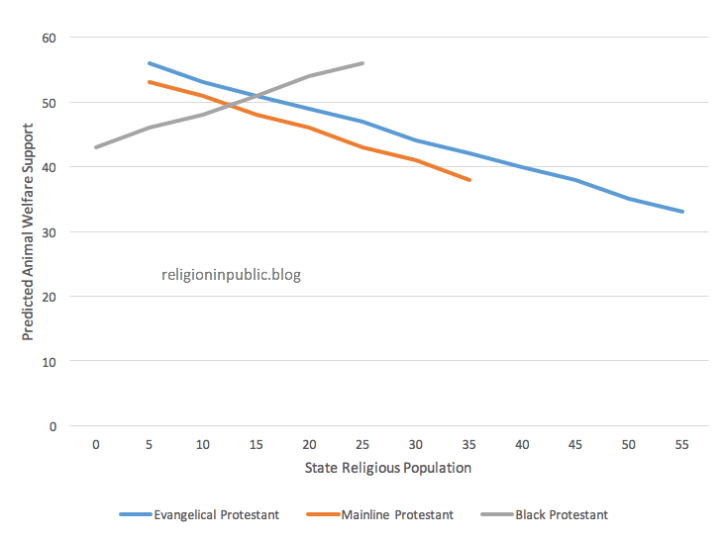

Senators represent religious constituencies, too. I find that when taking religious constituencies into consideration, as the Black Protestant share of the population increases, so too does the level of senatorial support for animal welfare. As Evangelical and Mainline Protestant shares of the population increase, senatorial animal welfare support decreases. The figure below depicts these relationships, providing predicted values of animal welfare support different given religious population levels. What explains these findings? This is something on which I elaborate in the article. The short version, however, is that some religious communities draw on a theological tradition that emphasizes human dominion over the earth and its creatures, while others emphasize stewardship. The stewardship approach suggests that humans have a responsibility to exercise care and protection over the natural world. Adherents to this approach are more likely to support animal welfare regulations and policies. The dominion approach suggests that the natural world is given to humans to use, redeem, and tame. Adherents to this approach, commonly evangelicals and Mormons, are less likely to support animal welfare regulations and policies.

What explains these findings? This is something on which I elaborate in the article. The short version, however, is that some religious communities draw on a theological tradition that emphasizes human dominion over the earth and its creatures, while others emphasize stewardship. The stewardship approach suggests that humans have a responsibility to exercise care and protection over the natural world. Adherents to this approach are more likely to support animal welfare regulations and policies. The dominion approach suggests that the natural world is given to humans to use, redeem, and tame. Adherents to this approach, commonly evangelicals and Mormons, are less likely to support animal welfare regulations and policies.

When explaining legislative behavior, much of the heavy lifting is done by partisanship. But even controlling for partisanship, religion shapes legislative behavior this issue and many others. I have tended to argue that when this happens legislators act on behalf of group-based cultural norms (e.g., traditionalism versus progressivism). That is, communities of believers share a way of life informed by religious creeds and a shared social status. This shared sense of being tells us who we are and what behaviors comport with that identity. So when an evangelical legislator casts a pro-life vote, she affirms her religious values, as well as a larger set of cultural values that encourage traditional family and social relationships.

The important thing to remember, however, is that issues are not inherently cultural. They are framed as such by political and religious elites; the upshot is that the myriad political issues that implicate religion may not (yet) have a clear cultural alignment, making culture a less useful heuristic. This is more likely with lower salience issues. In other words, as we think about expanding the potential scope of religious effects to include lower salience issues, the cultural implications are less obvious than they are with, say, abortion. This makes their politics a bit less predictable and a lot more interesting. Djupe’s post on the Evangelical Immigration Table certainly speaks to this. These issues represent the higher hanging fruit, and they are overdue for examination.

Elizabeth A. Oldmixon is associate professor of political science at the University of North Texas and editor-in-chief of Politics and Religion. She can be contacted via Twitter. Further information can be found on her personal website.

Notes

[1] True confession: I wrote this post in part as an excuse to share a picture of my dogs, Pup Francis and Ruth Ginsburg.

[2] “Don’t act surprised, you guys, cuz I wrote [some of] ‘em.”

[3] In 2015 Pew Research Center recently asked Americans what they thought Congress’s and the president’s top priorities should be, providing respondents with a list of 24 possible issues. Animal welfare was not even included on its list.

[4] I haven’t archived the dataset yet, as the article is not yet in print. I am happy to share nevertheless. Drop me a line if you’d like to have it.

[5] In the model on which this figure is based, Mainline Protestants comprise the reference category. Evangelicals are indistinguishable from Mainline Protestants.