By Elizabeth A. Oldmixon

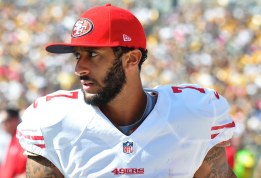

Last year, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick garnered national headlines when he started taking a knee during the national anthem in protest of police  violence and racial oppression. He was joined by a handful of other professional athletes, including Megan Rapinoe and Eric Reid. Kaepernick became a free agent at the end of the season. He remains unsigned, and the NFL has had to contend with allegations that he has been blackballed.

violence and racial oppression. He was joined by a handful of other professional athletes, including Megan Rapinoe and Eric Reid. Kaepernick became a free agent at the end of the season. He remains unsigned, and the NFL has had to contend with allegations that he has been blackballed.

The #takeaknee protests continued on, but they remained at the margins until this past Friday, when President Trump suggested that NFL owners should fire protesting players: “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. He is fired. He’s fired!'” Shortly thereafter, the NFL, as well as many professional athletes and teams, issued statements rebutting the president, though not all by name. (And somewhere in the mix the president dis-invited Stephen Curry to the White House.)

It is an unusual thing indeed for an American president to call for citizens to face economic sanctions as punishment for political speech. It is worth remembering this bit from Justice Robert Jackson’s majority opinion in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1943):

If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion, or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein. If there are any circumstances which permit an exception, they do not now occur to us. We think the action of the local authorities in compelling the flag salute and pledge transcends constitutional limitations on their power, and invades the sphere of intellect and spirit which it is the purpose of the First Amendment to our Constitution to reserve from all official control.

The upshot of all this is that on Sunday, many more players decided to take a knee during the national anthem. Whether or not you approve of the protests—and many do not—they are very much a part of the American tradition of civil religion. Civil religion is the widely diffused, implicit tendency among many Americans to see the United States, its history, and its purpose in religious terms. Its roots go back to John Winthrop’s 1630 admonition to the colonists on the Arabella that they:

shall be as a citty upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon us. Soe that if wee shall deale falsely with our God in this worke wee haue undertaken, and soe cause him to withdrawe his present help from us, wee shall be made a story and a by-word through the world [sic].

The Puritans considered themselves to be a new Israel, chosen and delivered by God from oppression, and bound by a new covenant. This imbues the symbols of national identity, such as the flag or the national anthem, with transcendent meaning for many Americans. It is the root of American exceptionalism, and it is why American presidents use religious imagery when they talk about the country. [1] In that sense, the #takeaknee protestors aren’t simply protesting racial inequality, they are questioning our shared national virtue, and with good reason in their view (mine too, full disclosure).

Civil religion has two dimensions in potential tension with each other. The first is priestly civil religion, which elevates America’s chosenness and cements the loyalty of its people. This is expressed in the honor and reverence we give to the flag and the U.S. Constitution, and it is celebrated with fireworks and patriotic songs. It is fully consistent with the Puritan idea that we are a virtuous, anointed people. The second is prophetic civil religion, which calls us to account when we sin, when we are not living up to the terms of the covenant. It is the less fun dimension, but it is crucial lest we fetishize the state.

Being a “covenant people” means that we live under certain obligations. As sociologist Robert Bellah observes, “our nation stands under higher judgment.” When the Israelites of the Hebrew Bible strayed from their covenant obligations, we are told that God sent prophets to call them to account. They tended to be pretty unpopular—no one likes a scold. So too did many look askance at America’s 20th century prophets—people such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Martin Luther King, Jr., Harvey Milk, and Dorothy Day, whose words and actions suggested that we weren’t living up to our own ideals.

Back to the NFL. Many Americans object to the #takeaknee protest. Some consider it an affront to those who died in military service, while others view the protestors as insufficiently grateful for their success. Be that as it may, protesting injustice has deep roots in the American tradition. And, given the prevalence of a prophetic civil religious style among Black churches in this country, it comes as no surprise that Black athletes are using their status to engage in reverent protest that shines a light on the sin of racial oppression, just as Tommie Smith and John Carlos did in 1968. It’s as American as saluting the flag, and we should probably give thanks. After all, priestly civil religion on its own elevates the state above its people and threatens our unalienable rights.

Elizabeth A. Oldmixon is professor of political science at the University of North Texas and editor-in-chief of Politics and Religion. She can be contacted via Twitter. Further information can be found on her personal website.

Notes

[1] See, for example, President Reagan’s farewell address.

[…] 2. The #TakeAKnee Protest is as American as Saluting the Flag…Swear to God […]

LikeLike