By Ryan L. Claassen, Paul A. Djupe, Andrew R. Lewis, and Jacob R. Neiheisel

[Note: This appeared first on the Political Behavior blog. Image note: President Donald Trump attends the Liberty University Commencement Ceremony and delivers remarks Saturday, May 13, 2017, Lynchburg, Virginia. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead).]

Is the Republican Party the party of religious Americans? Is the Democratic Party the party of secular Americans? The answer to these questions is a resounding, “NO!” Evidence of religious diversity in American society and within both major political parties abounds. And numerous social scientific studies have done much to unravel persistent stereotypes about the extent of the religious divide in American politics.

But what if many Americans are living their political lives steadfastly believing that the answer to these questions is a resounding, “YES!”? Such misperceptions could certainly be forgiven by anyone familiar with partisan rhetoric regarding the religious divide in American politics. Yet, these misperceptions have the potential to become self-fulfilling. Do beliefs that exaggerate the religious divide in American politics transform a mythical divide into a real one, with the perceived group divide contributing to polarization?

Our forthcoming article in Political Behavior investigates just what Americans believe about the religious make-up of the parties and explores the implications of those beliefs for partisan identity and partisan sentiment.

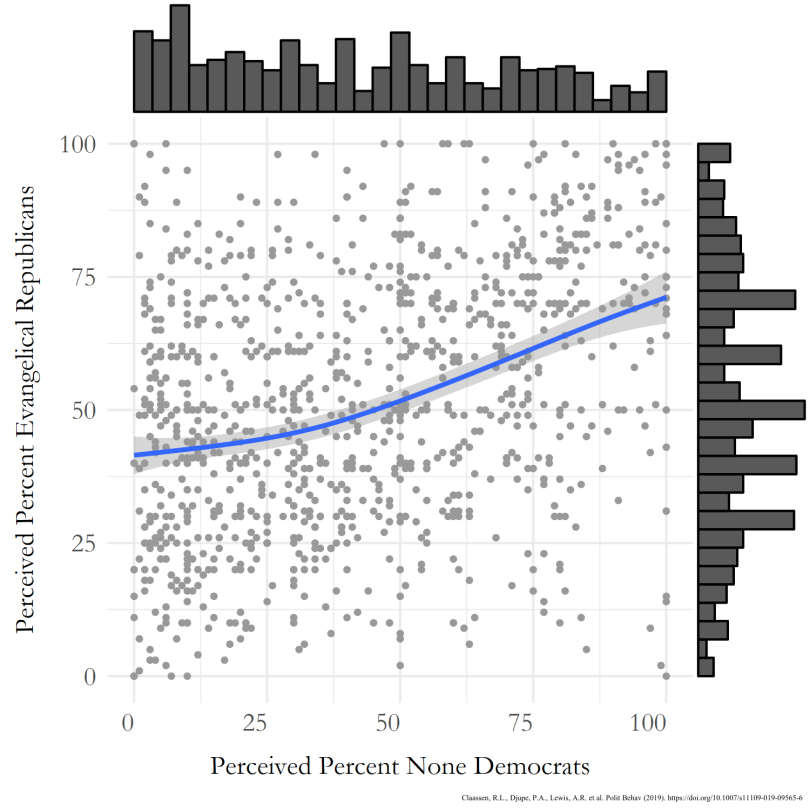

In three different national surveys, we asked samples of Americans about the percent of Republicans they believe are evangelicals and the percent of Democrats they believe are seculars. Figure 1 demonstrates that perceptions of the religious make-up of the parties span the entire range of possibilities, but there is a weak, statistically significant connection – perceiving that the Republican Party is full of evangelicals is related to perceiving that the Democratic Party is full of seculars.

Figure 1 – How Beliefs about the Evangelical Percent of Republicans and Religious None Percent of Democrats are Distributed and Linked (March 2016 Data)

To assess the connections between these perceptions and partisanship, it is important to analyze them by sub-groups, which we do in Figure 2. While our samples mirror national proportions, Figure 2 demonstrates that even averaging does little to improve the accuracy of Americans’ perceptions. In particular, members of groups involved in the stereotypical divide (evangelicals and seculars) exaggerate the divide in their beliefs, though Evangelicals do so to a greater degree.

Figure 2 – Beliefs about the Percent of Nones in the Democratic Party and Evangelicals in the Republican Party by Subgroups (November 2015 Data)

So, many Americans perceive there to be a religious divide in American politics that does not exist to such a degree, but to what end? Theoretically, we suggest that perceptions about the composition of the parties provide crucial linking information that helps individuals connect their group identities with a partisan identity. The theory builds upon the traditional political science story regarding the centrality of groups in party coalitions that have long been discussed (see e.g., Achen and Bartels 2016; Ahler and Sood 2018; Mason and Wronski 2018).

Using the same three datasets, we estimated models of party identification (standard seven-point scale) and party affect (difference of party thermometers) as a function of religious group identity, perception of the religious composition of the parties, and a series of statistical interactions that allow for the possibility that members of different groups will use those perceptions differently to shape their partisan commitments. Figure 3 shows that group members do in fact use perceptions about the religious composition of the parties in both positive (i.e., by identifying with the party in which they believe there are many coreligionists) and negative ways (i.e., by not identifying with the party in which they believe there are many antagonist group members). For instance, across all three datasets (top row), religious people (solid, black line) who perceived the Democratic Party to have more nones are more Republican. In the bottom row, evangelicals who perceive the Republican Party to have more evangelicals are more Republican, while non-evangelicals are more Democratic.

Figure 3 – The Interactive Effects of Religious Group Membership and Perceptions of Party Composition on Partisanship (All Three Data Sources)

There is a strong tendency for stereotypical beliefs about religious divisions in American parties to reinforce those divisions as group members use those beliefs to find partisan homes. Interestingly, there is an asymmetry in the magnitude of the effect, however, with evangelicals and religious people leaning more heavily on their perceptions than seculars. Countering this rather dismal news, we also note that many Americans hold counter-stereotypical perceptions, which serve to undermine polarization. For example, some evangelicals believe that many Democrats are evangelicals and their perceptions about the religious divide push them toward the Democratic Party. The pattern repeats for seculars who believe many Republicans are secular. Finally, seculars and evangelicals who hold more accurate perceptions are not terribly polarized politically (where the lines cross in Figure 3, the different groups profess similar partisanship).

There is much evidence here to worry about. The hyperbolic quality of political debate in the country is affecting Americans’ perceptions about the religious divide for the worse and these inaccurate perceptions are very polarizing. If beliefs about the state of the world are fueled by rhetoric portraying each side as locked in an existential battle, perceived religious divisions in American politics might prove to be terribly consequential. That is, exaggerated beliefs about the number of Republicans who are evangelicals, for instance, might lead more evangelicals to become Republican over time.

The silver lining here is that we find two possible antidotes to what could be a spiral of polarization. First, counter-stereotypical beliefs push in the other direction. Nurturing these would reduce polarization over time. Second, and even more appealing, Americans with accurate perceptions appear less polarized. A truce in the culture wars is possible, but inaccurate perceptions must be corrected.

About the authors:

Ryan L. Claassen is a professor of Political Science at Kent State University, author of Godless Democrats and Pious Republicans (2015), coeditor of The Evangelical Crackup (2018), and author and coauthor of numerous articles in political science journals. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Andrew R. Lewis is an associate professor of Political Science at the University of Cincinnati, Public Fellow with PRRI, and author of The Rights Turn in Conservative Christian Politics (2017). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of Political Science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. His work has been published in the American Journal of Political Science, Legislative Studies Quarterly, Political Research Quarterly, and American Politics Research. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

[…] heavily skewed by group perceptions of what a Democrat or Republican looks like (for instance, check this out for results about perceptions of the religious composition of the […]

LikeLike