By John Compton

[Note: This was originally posted at A House Divided]

For the past three years, scholars and pundits have been working overtime to explain why white evangelicals backed Donald Trump – a thrice-married former casino owner with a fondness for the company of porn stars – in the 2016 election. At the risk of oversimplifying, much of the resulting commentary can be grouped into one of two theories. The first theory, which is embraced by many journalists and some historians, views the Trump-evangelical relationship as straightforwardly transactional. Evangelicals care deeply about a narrow range of issues, including abortion and religious free exercise accommodations; and candidate Trump, notwithstanding his personal failings, made a credible promise to pursue evangelicals’ preferred policies in these areas.

The second theory, which is more popular with political scientists, views white evangelicals’ Trump support not as the result of an explicit policy bargain, but rather as the manifestation of a deep-seated, identity-based affinity between evangelicalism and Republicanism. In short, because devout white evangelicals strongly identify with the Republican party, there was never any real chance that candidate Trump’s personal sins would drive them into the Democratic camp (or to third-party candidates). Trump’s policy promises certainly didn’t hurt his standing with evangelicals. But even without them, he was well positioned to win the evangelical vote in a landslide.

As a political scientist, it is perhaps unsurprising that I find the latter account more plausible. Indeed, as scholars have gathered more data concerning evangelicals’ views of Trump and his policies, it seems increasingly clear that specifically religious or “moral” considerations played at best a modest role in driving white evangelical support for the President. And yet, I think it is worth asking why the myth of a discrete evangelical voting bloc motivated by explicitly religious concerns persists. Why, for example, do so many pundits – and their readers – continue to believe that evangelical leaders hold the power to sway presidential elections? Why do candidates – on both the left and the right – continue to pepper their stump speeches with targeted appeals to religious voters? And why do prominent newspapers continue to publish op-eds suggesting that better messaging on the part of Democratic candidates might prompt an evangelical exodus from the Republican coalition?

Part of the explanation, as I argue in a forthcoming book, can be traced to a critical but underexamined transformation in the institutional structure of American Protestantism. In short, for much of American history, Protestant religious elites actually did have the power to shape their followers’ political behavior in significant ways, at least on occasion. But the elites in question were typically theologically liberal mainline Protestants, and much of their power derived from a now-defunct ecumenical infrastructure that facilitated the transmission of information and arguments from elites to average churchgoers (and vice versa). Most of today’s evangelical Protestant leaders, in contrast, possess neither the intrinsic religious authority nor the institutional resources necessary to influence their purported followers’ views of particular candidates or policies. On the contrary, evangelical elites tend to take their marching orders from the men and women in the pews – men and women who, again, overwhelmingly identify as conservative Republicans.

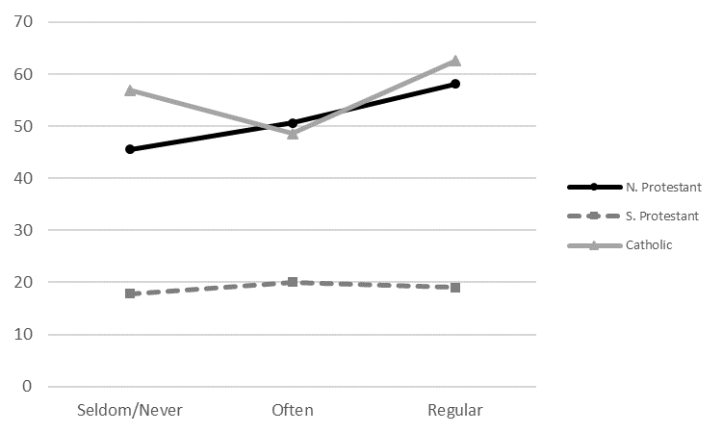

For an example of the political influence wielded by mainline Protestant elites prior to the 1970s, one need look no further than the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Beginning in the early spring of 1963, leaders of the Episcopal, Congregational (UCC), Methodist, (Northern) Presbyterian and other mainline denominations joined forces with Catholic and Jewish leaders to endorse President Kennedy’s proposal for a meaningful federal civil rights bill. Over the following year, mainline elites conducted a massive educational and mobilization campaign designed to frame the bill’s passage as a religious imperative. And based on data collected for the American National Election Studies (ANES), it appears that they succeeded. By 1964, northern white Protestants who attended services regularly – and were therefore more likely to be exposed to religion-based appeals for civil rights reform – were significantly more likely than their less pious neighbors to favor passage of the Civil Rights Act, even after controlling for other demographic determinants of racial liberalism. (Previous ANES studies indicated no relationship between church attendance and racial liberalism.)

Figure 1 – Church Attendance and Support for 1964 Civil Rights Act (whites only)

The secret to the success of the mainline Protestant civil rights push was twofold. First, mainline elites benefited from the fact that mainline membership was an important marker of socioeconomic status. At a time when upwardly mobile Protestants routinely transferred their church memberships from Baptist or Pentecostal churches to Presbyterian or Episcopalian ones, mainline leaders’ views concerning important questions of public policy carried weight with middle-class citizens seeking admission to the upper rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. To be sure, some rank-and-file churchgoers grumbled about their leaders’ liberal stances on issues like civil rights and the communist threat. But believers who wanted the socioeconomic benefits of mainline church membership were nonetheless incentivized to at least give a serious hearing to denominational elites.

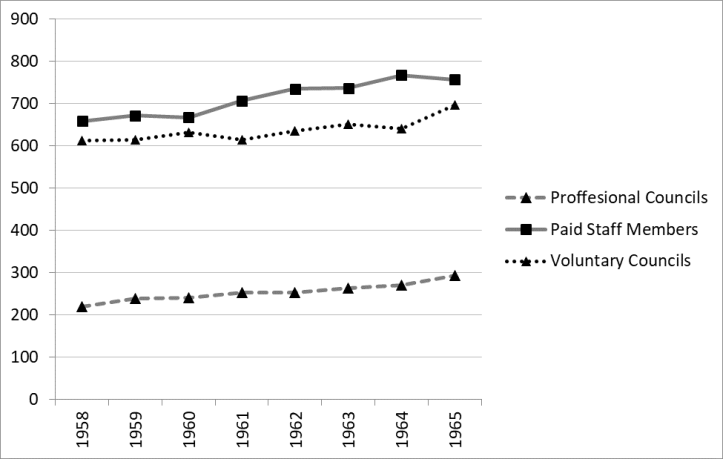

Even more important than the socioeconomic pull of mainline church membership, however, was the ecumenical infrastructure that mainline Protestant leaders had carefully constructed during the first two-thirds of the twentieth century. The National Council of Churches (NCC), a deep-pocketed umbrella group, facilitated the Protestant civil rights push with the help of a vast network of state and local church councils. Largely a Northern phenomenon, the Protestant church councils had by the early 1960s honed their advocacy skills in dozens of generally left-leaning political campaigns – from supporting the formation of the United Nations to protesting the investigative tactics employed by McCarthy Era congressional committees. More to the point, they were flush with cash: by 1959, the combined annual budgets of the nation’s 300 or so local church councils exceeded $100 million in present-day dollars. In 1963 and 1964, they advanced the civil rights cause in a variety of ways: coordinating traveling teams of ministers and activists to address Sunday services, organizing statewide “legislative conferences” to pressure undecided members of Congress, and sending countless busloads of churchgoers to the Capitol to lobby their representatives.

Figure 2 – Growth of State and Local Protestant Church Council Network, 1958-1965

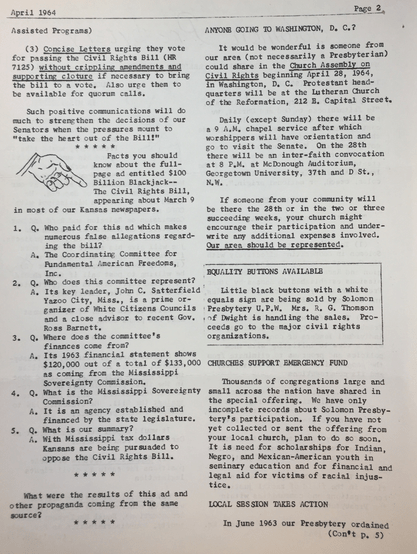

At the same time, individual mainline denominations, acting through preexisting federated organizational structures, launched a network of grassroots civil rights committees that simultaneously worked to educate churchgoers about the proposed bill and to pressure undecided lawmakers. In the case of the Presbyterians, federated group structures of the sort studied by Theda Skocpol allowed denominational leaders to create an interstate network of local and regional civil rights committees almost overnight; forty such committees were formed at the synod and presbytery levels between June 1963 and January 1964, with hundreds more taking shape in individual congregations. The upshot was that, even in the most remote parts of the Great Plains, individual congregations were able to direct a steady flow of letters, telegrams, and phone calls at the handful of Midwestern Republican Senators whose votes were destined to determine the success or failure of the civil rights bill.

Figure 3 – Newsletter of the Solomon (KS) Presbytery Civil Rights Commission

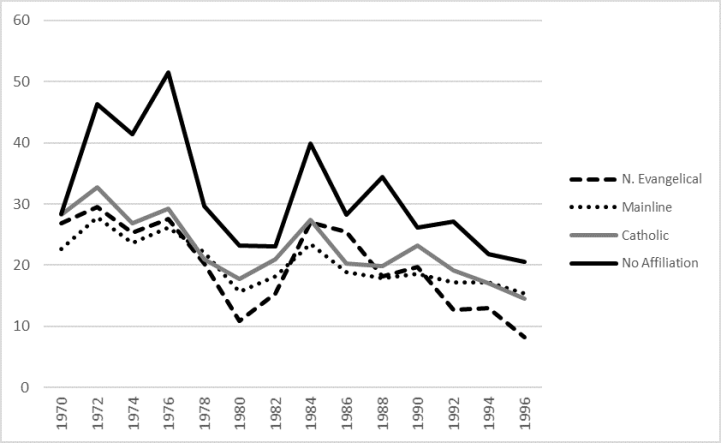

In retrospect, the 1963-1964 civil rights push marked the apex of mainline elites’ political influence. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, most of the mainline denominations began to experience sharp attendance declines and budget shortfalls, which led to the rapid decay of the Protestant ecumenical movement, as well as the broader church council network that was its most important institutional manifestation. At roughly the same time, evangelical churches and denominations began experiencing strong growth – a phenomenon that led Time magazine, as early as 1969, to declare that evangelicals were the “new pacesetters” of American Christianity. To many observers, these events resembled a changing of the guard, with politically conservative evangelical elites taking over the political space previously occupied by their left-leaning mainline rivals. This interpretation was seemingly confirmed in 1980, when Ronald Reagan won the White House with strong backing from Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority and other evangelical-dominated “Religious Right” groups.

But the post-1980 age of evangelical hegemony was, in at least one important sense, utterly unlike the previous period of mainline dominance. In short, the robust organizational structures that allowed mid-century mainline leaders to exert some degree of influence over their followers’ political convictions were nowhere to be found in American evangelicalism. The largest denomination traditionally classified as evangelical, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), boasted a highly decentralized structure whose primary purpose was to discourage top-down educational or mobilization efforts. The largest evangelical ecumenical group, the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), suffered the consequences of a similarly skeletal infrastructure. Finally, many evangelicals belonged to a growing network of more or less independent megachurches – many of which remained completely cut off from denominational and ecumenical activities.

The institutional weakness of American evangelicalism meant that evangelical elites – in sharp contrast to their mainline predecessors – always served at the pleasure of the rank and file. Highly vulnerable to shifts in public opinion, they either tracked the political mood of the lower-middle-class white electorate, or else became shepherds without flocks. To illustrate the point, one need only recall that, as late as the mid-1970s, many prominent evangelicals – including President Jimmy Carter, Senator Mark Hatfield (R-OR), Congressman John B. Anderson (R-IL), Christianity Today editor Harold Lindsell, popular writer Francis Schaeffer, and the theologian Carl Henry – staked out positions on the center-left of the political spectrum. While most of these figures – though not Hatfield and Anderson – staunchly opposed the weakening of patriarchal family structures, most were also supportive of stricter environmental regulation and generally suspicious of big business.

But at the end of the decade, when the white electorate lurched rightward, figures like Hatfield, Anderson, and Schaeffer faced a choice: endorse the politics of the conservative backlash or be banished from the movement. Those who, like Anderson, remained steadfast in their center-left convictions were summarily excommunicated from the ranks of mainstream evangelicalism. (Anderson received somewhere around 7 percent of the evangelical vote in his longshot 1980 bid for the presidency). Others, like Lindsell and Schaeffer, did their best to disavow the views they had espoused in the mid-1970s. Suddenly unconcerned about environmental degradation or the human cost of deregulation, both men spent the early 1980s providing biblical cover for President Reagan’s libertarian economic agenda.

Finally, a handful of evangelical leaders placed early bets on the conservative insurgency and were as a result catapulted to national prominence. This is how a moderately successful Baptist televangelist named Jerry Falwell became a media sensation. Although Falwell is often cast in a prophetic role – the uncompromising zealot leading his flock into the culture wars – it would be more accurate to say that he simply sensed before others which way the political winds were blowing (thanks in part to his close connections to such “New Right” political operatives as Paul Weyrich and Richard Viguerie). Realizing that the white electorate as a whole was tracking rightward on issues ranging from civil rights to taxes and abortion, Falwell endorsed the full panoply of New Right causes and was rewarded with a brief but successful career as a Republican power broker.

Figure 4 – White Support for Federal Civil Rights Initiatives by Religious Tradition, 1970-1996

The theologian Carl Henry, who never fully endorsed the evangelical movement’s rightward shift (and who found himself marginalized as a result), was one of the first prominent evangelicals to recognize that institutional weakness rendered the movement uniquely vulnerable to political capture. As early as 1972, Henry backed out of a scheduled appearance at a massive evangelical youth gathering known as “Explo’ 72” when he realized that the event’s organizers would not tolerate serious discussion of subjects like the environment or race relations for fear of offending potential converts (though appeals to patriotism and expressions of support for the Vietnam War were welcome). By the mid-1980s, the man who had done more than anyone else to render evangelicalism intellectually respectable could only lament that evangelical elites were everywhere taking their political cues from the men and women in the pews. Political “entrepreneurs” like Falwell, he wrote, were guilty of “exploit[ing]” the “evangelical movement’s hard-won prominence…in view of constituency appeal and in quest of potential funding.”

Figure 5 – Carl Henry Letter to Harold Lindsell Declining Invitation to Address “Explo’ 72”

American evangelicalism’s institutional weakness also helps to explain why commentators predicting the imminent emergence of an evangelical left – or even an evangelical center – are so regularly disappointed. Although several noted evangelical leaders have in recent years parted ways with Republican orthodoxy, their favored causes have generally failed to gain traction with – and in some were actively repudiated by – the rank and file. In the early 2000s, concerted efforts to focus evangelicals’ energies on climate change and foreign aid produced little change in the views of average churchgoers. More recently, in 2013-14, a massive push for comprehensive immigration reform – sponsored by the NAE, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU), and a host of other evangelical entities – yielded similarly lackluster results. Indeed, polls conducted at the height of the pro-reform campaign found that fully 62 percent of white evangelicals agreed with the statement: “We should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries.”

In the winter of 2015-2016, when Donald Trump emerged as a serious contender for the Republican nomination, commentators were split on whether evangelicals could be persuaded to support a candidate whose personal life was so sharply at odds with biblical teachings. Many observers suspected that Trump would win the evangelical vote, but by a smaller margin than other recent GOP nominees, and that a mediocre showing with evangelicals might well cost the GOP the election. Obviously, such predictions proved to be wildly off the mark. But the larger point is that they rested on assumptions that, at least in hindsight, should have been jettisoned following the unsuccessful elite-led reform campaigns of the early 2000s. Long before 2016, in other words, it should have been clear that white evangelicals were likely to stick with the Republican nominee, regardless of whatever objections their purported religious leaders might raise to the idea of a Trump presidency.

And this is precisely what happened. Although many evangelical elites – from the SBC’s Russell Moore, to the editors of Christianity Today, to the best-selling author Max Lucado – strongly condemned candidate Trump’s rhetoric and aspects of his policy agenda, their pleas mostly escaped the notice of rank-and-file churchgoers. In fact, one post-election study found that around 45 percent of evangelicals believed that both Moore and Christianity Today had endorsed Trump. And the story was much the same at the congregational level, where cues from ministers seem to have exerted little influence over the electoral choices of average evangelicals.

In light of such evidence, it makes little sense to blame (or credit) evangelical elites for fueling the rise of either Donald Trump or the broader strain of conservative populism he represents. Although it is true that several prominent evangelical leaders engaged in transactional negotiations with candidate Trump – some of them very personal in nature – before delivering their 2016 endorsements, there is scant evidence that the details of these arrangements filtered down to average believers, and even less evidence that knowledge of Trump’s specific promises with respect to abortion policy or “religious liberty” exerted a significant impact on evangelicals’ voting behavior. For the same reason, it is unlikely that the pronouncements of evangelical elites will significantly impact the 2020 contest. Given the collapse of the socioeconomic dynamics and institutional structures that facilitated Protestant elite influence in previous periods of American history, evangelical leaders hoping to maintain their status within the movement will continue to have little choice but to echo the political views of their followers.

John Compton (@JohnWCompton2) is associate professor and chair of political science at Chapman University. His first book, The Evangelical Origins of the Living Constitution, was published by Harvard University Press in 2014. His forthcoming book from Oxford University Press is The End of Empathy: Why White Protestants Stopped Loving Their Neighbors.

[…] seem respectable. However, in some religious groups, like Catholics and mainline Protestants, the average level of attendance has continued to atrophy. So has their share of the population, though. It is possible that there […]

LikeLike