by Ryan P. Burge, Eastern Illinois University

Can you be a Muslim and identify as born-again or evangelical? The pastors and theologians who are reading this are engaging in a lot of head shaking right now, but hear me out. Does a Muslim checking the box next to “born-again or evangelical” actually tell us something about how their view themselves in social, political, and religious space? I think the answer to that question is “yes” and I don’t just believe it’s an issue of measurement error or poor survey design. Instead, it also tells us something deeply profound about what terms like “evangelical” mean to a Muslim (or really any non-Protestant identifier) over the last decade.

The CCES has been asking respondents a series of questions about their religious belonging and behavior dating back to 2006. They ask a question about respondents’ present religion and Muslim is the sixth option offered, but then they also ask: “Would you describe yourself as a “born again” or evangelical Christian or not?” The two response options are yes and no.

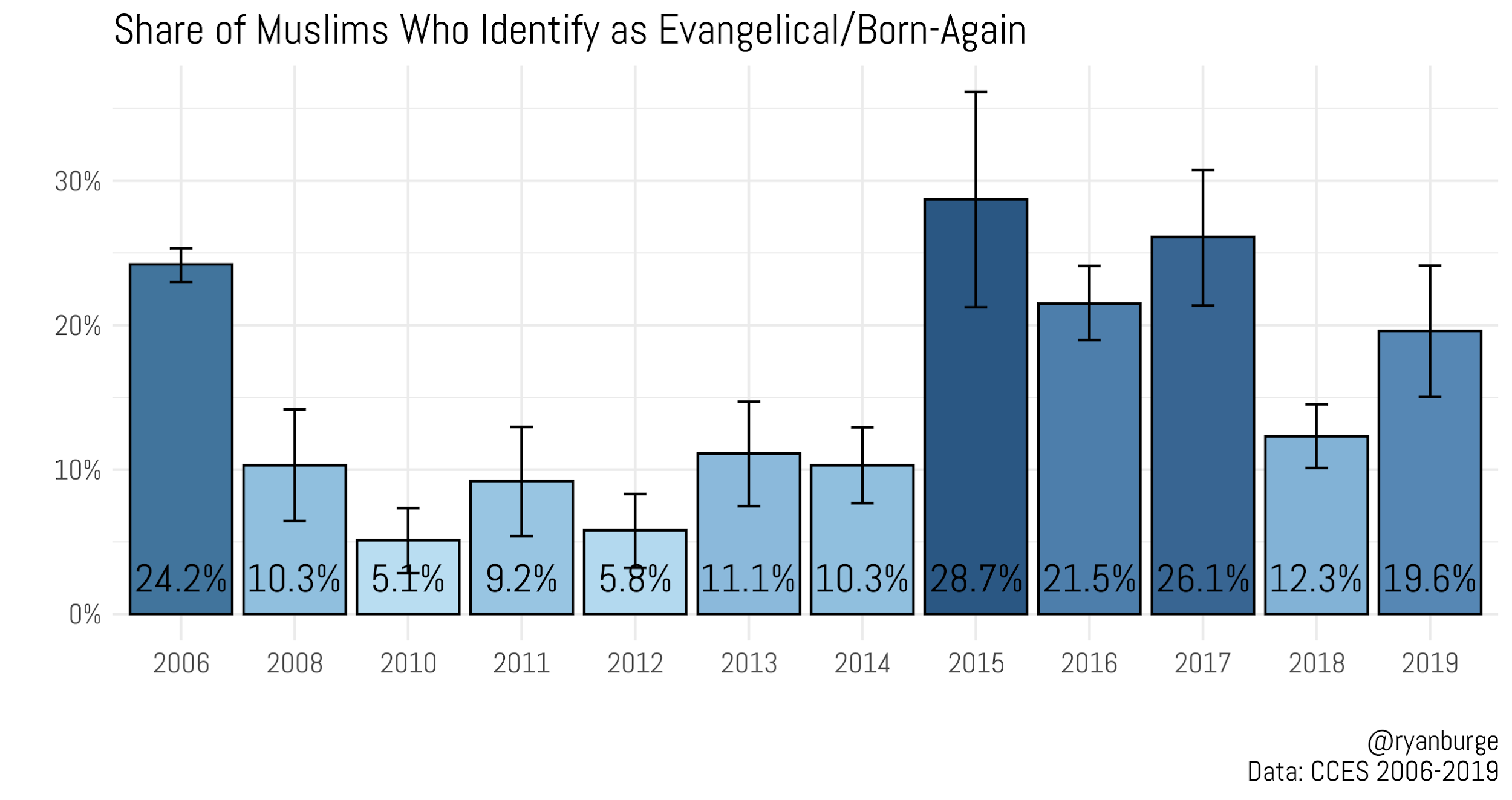

Let’s start by tracking how the share of Muslims who identify as born-again or evangelical over the last thirteen years. To get a sense of scale. The total sample of this series is nearly 447,000 respondents. The smallest sample year was 14,250, the largest was 64,600.

I do need to contextualize these numbers, though. Just 1% of Americans are Muslims and just about 17% of them identify as evangelical in the overall sample. So, this isn’t a huge part of the American population.

It’s best to describe these results as inconsistent. Let’s assume that 2006 is an outlier – I’ve seen a lot of weird things from that sample. If that’s excluded, the share of Muslims who are evangelical averaged 8-10% from 2008 through 2014. With the margin of error, there’s not much difference across that time period. However, something shifted in 2015 and the percentage of evangelical Muslims jumped into the mid to low 20s for the next three years. It dropped again to 12% in 2018 only to rise back to nearly 20% in 2019.

It’s fair to say that there’s no discernible pattern there, as least not one that I can easily pinpoint. That huge jump between 2014 and 2015 may be related to the emergence of Donald Trump, but that would be a stretch. And it still doesn’t fully explain the dip in 2018, which could also be an outlier.

Let’s try to explore one potential reason that a Muslim would chose to identify as born-again/evangelical – they just don’t have a good grasp of the question. The best proxy to get to the root of that is education level. Put simply – are more educated Muslims less likely to identify as evangelical?

It does appear that those Muslims with less education are more likely to identify as evangelical. For instance, 57% of all evangelical Muslims have a high school diploma or less, while it’s only 38% of Muslims who don’t identify as evangelical. And at the top end, 19% of Muslims who are evangelical have a four-year college degree, compared to 26% of non-evangelical Muslims. So, maybe this has something to do with understanding the question being asked.

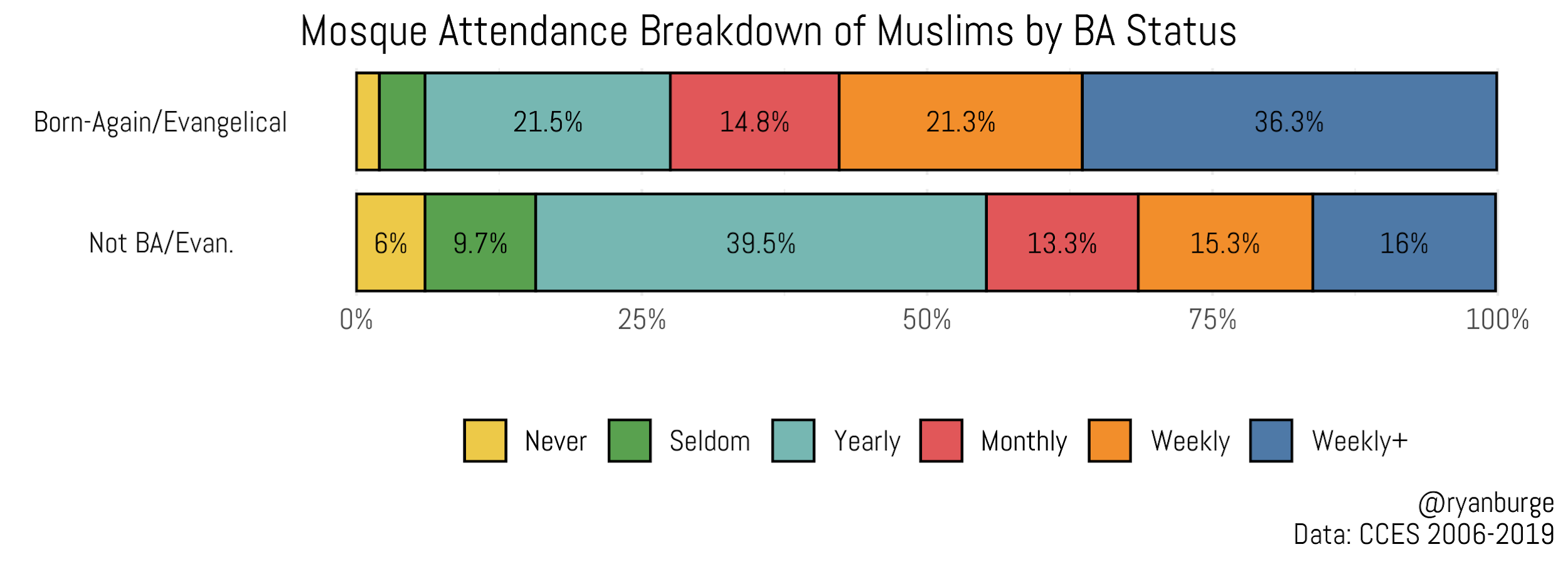

But, maybe this is about something else that is unrelated to awareness of the implications of the question. It’s possible that the term “evangelical” has become a proxy for “I am religious and very devout in my faith.” It’s a way to signal to the world that I am just a Muslim because of culture or heredity, but I’m born again because I deeply care about my faith. If so, we would expect Muslims who attend services at a mosque more frequently to identify as evangelical at higher rates.

And the data do seem to support that idea – 57% of Muslims who identify as evangelical say that they are at the mosque at least once a week. For non-evangelical Muslims, it’s much lower at just 31%. And yearly mosque attendance is twice as prevalent among non-evangelical Muslims than those who identify as “born-again or evangelical.” So, there does appear to be multiple factors driving this identity – it is both an issue of question awareness but also of religious devotion.

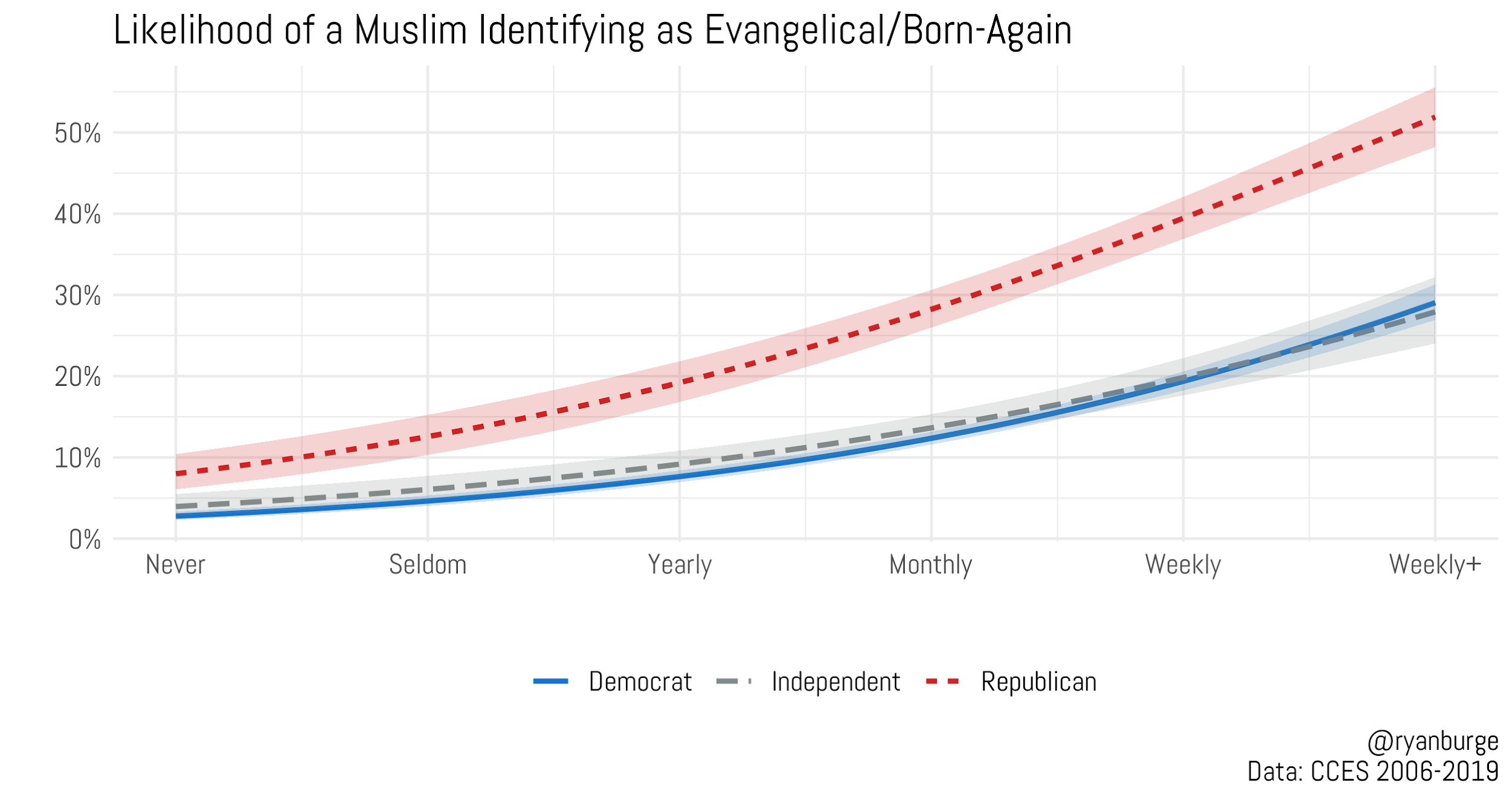

But, there’s still another possibility that always looms over these discussions – politics. As I’ve written about before, evangelicalism in the United States is not declining because more people are adopting the label for seemingly political reasons. The evidence of that is that the share of politically conservative, self-identified evangelicals who rarely attend church has risen nearly 50% in a decade.

So, maybe a Muslim taking on the evangelical moniker is really doing so for reasons that are enmeshed in politics. To test that, I ran a regression model with some basic controls for gender, income, and education. The thing I am trying to predict is the likelihood of a Muslim embracing the evangelical label.

A quick glance gets us to an unmistakable conclusion – being a Republican makes a Muslim much more likely to identify as an evangelical. Amongst those attending yearly or less, this gap is fairly modest, at 5-10 percentage points. However, the gap begins to widen as attendance increases. Among those who attend services multiple times a week, about 30% of Democrats and Independents identify as evangelical, but it’s over half of Republican Muslims who attend that frequently.

There are two takeaways for me here. The first is that evangelicalism has become a shorthand for “very devout.” That’s evidenced by the fact that as mosque attendance increases, so does an evangelical identity regardless of partisanship. However, clearly evangelicalism has melded with Republicanism in the United States for non-Christian religious groups.

I’m left with this really interesting conclusion. The perception among non-Protestants is that evangelicalism is a badge of religious devotion for Americans of faith. They identify with it even though it’s not theologically congruent with many of their traditions. But for a lot of Protestants, it’s become more of a social and political designation and less of a religious one. For Muslims Republicans, this is a way to identify more completely with their partisan inclinations, while de-priotizing the fact that Islam doesn’t have a born-again component to its faith tradition.

It’s easy to chalk things like “born-again Muslims” to bad survey design or measurement, but if you peek under the hood just a bit, you begin to see that survey respondents are telling us something potentially profound by answering these questions in seemingly odd ways. So, yes, there are evangelical Muslims and it’s a meaningful signal.

Ryan P. Burge teaches political science at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. He can be contacted via Twitter or his personal website. Syntax for this post can be found here.

Nice piece, Ryan. I wonder if African-American Muslims might be playing an outsized role. Of course, this would depend on their share of Muslim identifiers. They might well interpret “evangelical” as you suggest.

LikeLiked by 1 person