By Kate Hunt and Amanda Friesen

Every year, conservative lawmakers in U.S. states introduce legislation to further restrict abortion. In 2021, the increase in both severity and numbers of these bills is likely due to former President Trump’s conservative appointments to the Supreme Court and the chance that Roe v. Wade decision could be overturned. Activists and social movement organizations (SMOs) are often involved in the mobilization of citizens and lobbyists in these efforts – relying on a variety of messages appealing to the sanctity of life, women’s rights, health equity, and so on. In the U.S. and other countries’ abortion debates, women are at the center of this debate. But what does it look like when there is an effort to involve men in conversations and mobilization around a “women’s issue” like reproductive justice? In our recent publication at the European Journal of Politics & Gender, we explore this question by analyzing the contents of SMO social media campaigns in Ireland.

On May 25, 2018, the Republic of Ireland held an historic referendum wherein the people voted to remove the Eighth Amendment. Since 1983, the Eighth Amendment had created a constitutional roadblock to liberalizing abortion laws because it acknowledged an equal right to life for a pregnant woman and the fetus she carried. As a result of the 2018 vote, Ireland’s government passed abortion legislation that moved the country from having one of Europe’s most restrictive regimes to allowing abortion for any reason up to 12 weeks into pregnancy.

In a country with a strong Catholic Church influence and decades of debates, the stakes were high and the campaign for votes and turnout was hard-fought. Media attention often focused on the gender split in public opinion and vote intention. Specifically, according to The Irish Times/Ipsos MRBI poll, 13 percent of men polled said that they had “no opinion” on the issue of abortion rights compared to 7 percent of women, leading to speculation about whether men were less likely to vote than women and felt “left out” of the conversation because it was a “woman’s issue.” Some reporting on the impending referendum even asked whether “rugby dads” could hold the key to the vote.

Observing this commentary on the role of men in this vote on pregnant people’s rights, we wondered how these gendered dynamics were addressed by the social movement organizations campaigning both for and against the repeal of the Eighth Amendment. We took to Twitter and tracked the patterns in appeals to men across two key accounts – the anti-repeal Love Both organizational account and the pro-repeal Together for Yes organizational account.

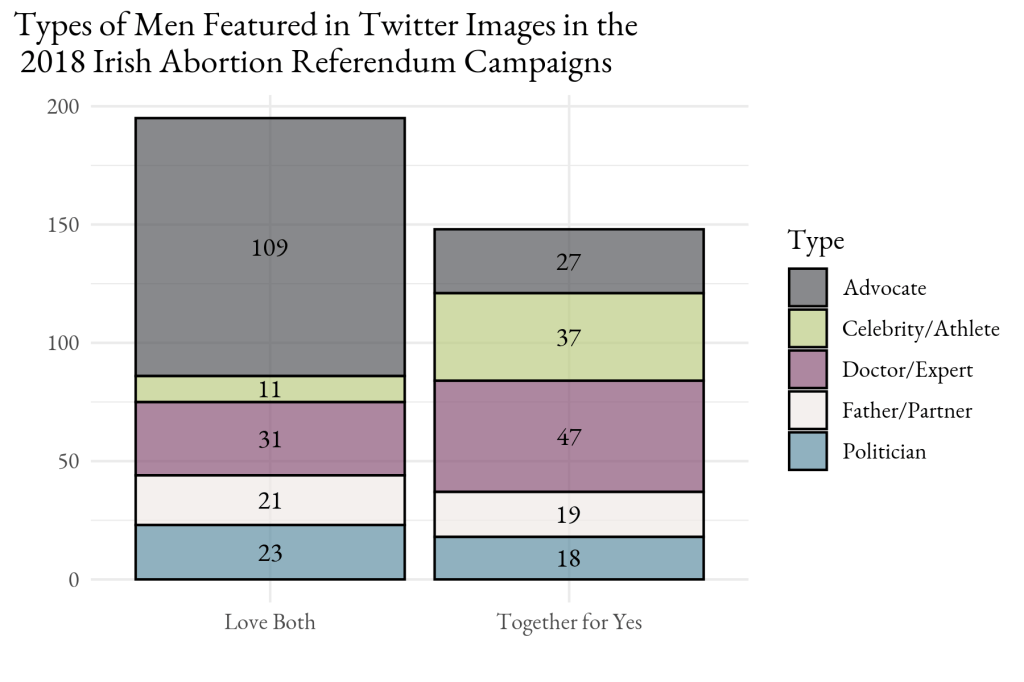

Over half of the tweets from each organization featured images or videos so a text-based content analysis would not capture the majority of the messages on display. We hand-coded 1000s of images for the presence of men, the type of men featured, and general themes that emerged. Through this process, we identified three roles in which men were placed in relation to abortion and the referendum campaign: men as advocates, men as impacted parties, and men as role models and experts. How they were represented within these roles varied, though there were some general themes that emerged, especially when it came to how masculinity was evoked.

When Together for Yes explicitly targeted men as a group in their mobilizing messages, 60% of these messages featured men who could be seen as role models for other men. While the messages tended to reinforce the importance of women’s rights and bodily autonomy, the images featured “manly men” such as athletes. For example, one image featured a group of male athletes grinning and holding up their fists. This image resonates with some conceptions of traditional masculinity, such as physical strength and occupational success, but the message that accompanied the image stated, “Men, if you think the 8th referendum is about healthcare, and that it’s for a woman to decide what healthcare she needs, then you are a YES voter.” Alternatively, while anti-repeal Love Both rarely addressed men specifically, their messages were more likely to refer to men’s roles as protectors, such as in a video where a male advocate explains, “as men, we have a duty to step up and protect both our partners and our children … Vote No, because you can’t repeal regret.”

In both of these examples, the tweets are consistent with the organizations’ general messages aimed at society more broadly. Together for Yes regularly posted messages about abortion as an issue of healthcare and something everyone needs to support, while a core message from Love Both was that the Eighth Amendment protected both women and children. In adjusting these messages to target men and their roles in relation to abortion, the organizations were able to stay on-brand while appealing to men as a group – and sometimes this included appeals to stereotypes about masculinity.

Our findings show that, typically, men are not explicitly targeted in mobilizations around reproductive justice. The case of Ireland’s 8th repeal shows that the general public was the core audience of both sides in the campaign. However, concerns about men’s participation did lead to some dedicated appeals to men on this so-called “women’s issue.”

While the pro-repeal organization included progressive messages about women’s rights alongside imagery that invoked traditional masculinity, the tactic raises questions about the long-term impact of these short-term strategies for gendered mobilization. The messages sent from both organizations reinforced the idea that “real men” care about the issue of abortion – either by opposing it or supporting women’s right to abortion. These findings suggest that even SMOs working toward women’s equality may rely on benevolent sexism in their attempts to mobilize men on behalf of women’s bodily autonomy, which threatens to undermine broader emancipatory goals. That is, continuing to reinforce paternalistic or sexist views even in pursuit of women’s rights could be problematic for long-term gender equity goals even if short-term progress is achieved.

Kate Hunt is a Visiting Assistant Professor of International Studies in the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies at Indiana University-Bloomington

Amanda Friesen is associate professor of Political Science and Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies and project director for the Center for the Study of Religion & American Culture at IUPUI.