By Oindrila Roy, Cottey College

Since the onset of the civil war in 2011, more than 6 million Syrians have been displaced from their own country. Despite the vulnerability of the displaced population, the original version of the Trump Administration’s Travel Ban (2017) barred Syrian refugees from entering the United States. Although this decision was severely opposed by many at home – including the evangelical church leadership – polls from the Pew Research Center showed lay evangelicals were unique among other religious groups in their significantly higher support for the policy.

Given the puzzling divide between evangelical parishioners and their church-elite, my recent publication in Politics and Religion explores factors shaping evangelical public opinion on Syrian refugees relative to other religious traditions, and the possible attitudinal differences on the issue within the evangelical community. My findings from a series of regression estimates using the American Nation Election Studies (ANES 2016) dataset reveal that lay evangelicals are not unique in their opposition. However, what sets them apart from other religious traditions is that they hold significantly higher levels of Muslim stereotypes, which in turn makes them more antagonistic toward refugees from Syria. Besides, measures of religiosity demonstrate significant impacts across religious traditions. Finally, the analysis cautions against treating lay evangelicals as a monolithic category, as interesting attitudinal differences are evident within the tradition.

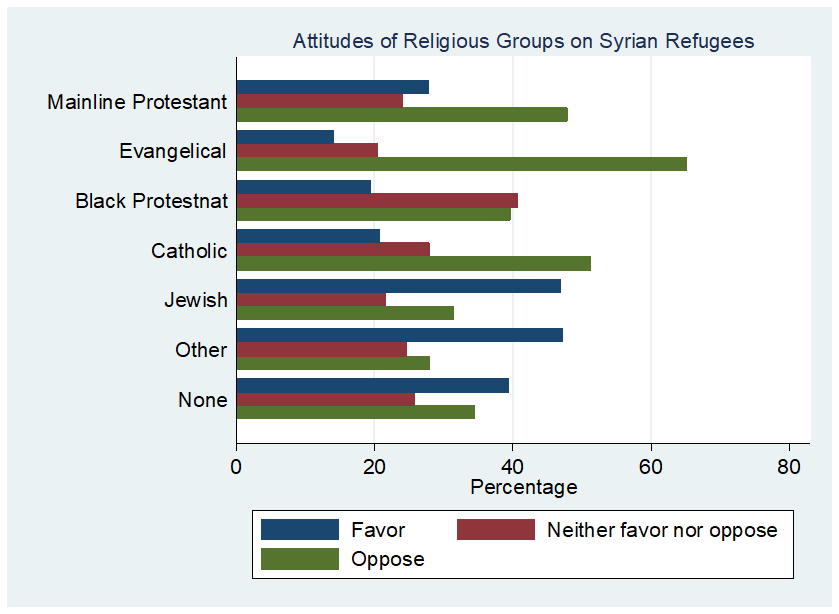

To assess attitudes on Syrian refugees across religious traditions, I measured the dependent variable using the ANES survey question: “Do you favor, oppose, or neither favor nor oppose allowing Syrian refugees to come to the United States?” In the first step of my analysis, I regressed the religious tradition measures on the dependent variable after controlling for the effects of church attendance, attitudes toward the Bible, political ideology, partisanship, Muslim stereotypes, and relevant demographic and socio-economic controls. The results from this model established that evangelicals were not unique in their opposition to Syrian refugees. In fact, compared to the baseline category of Mainliners, both Catholics and evangelicals remained significantly more opposed to Syrian refugees. This is in tune with the underlying distribution of attitudes. The figure below shows that the percentage of respondents opposing Syrian refugees among Catholics and evangelicals was higher than the percentage of mainliners with the same opinion.

Additionally, the model revealed some interesting findings regarding the measures for worship attendance and Bible authority. Those attending church more frequently were significantly less opposed to Syrian refugees than their infrequent counterparts (for similar findings in immigration politics literature, see Knoll (2009)). To delve deeper into this finding, I ran a simple bivariate model with the church attendance measure. In that model, frequent attendance was significantly related to greater opposition toward Syrian refugees. However, the sign flipped from positive (implying opposition) to negative (implying support) after introducing the religious identity and Bible authority measures. This implies that religious belonging and Bible authority were acting as suppressor variables in the bivariate model. In other words, frequent worship attendance worked in favor of Syrian refugees only when the impacts of Biblical authority and religious identity were parsed out from the effects of the church attendance measure.

Moreover, those who subscribed to the literal interpretation of the Scriptures were significantly more likely to oppose refugees than those believing in a more liberal reading of the same. This finding is not unusual, as Ben-Nun Bloom et al. (2015) found that religious beliefs favor immigrants only when the immigrant community shares the religious and ethnic background of the host community. Since most Syrian refugees are Muslim, a traditionalist interpretation of the Bible is unlikely to work in their favor.

To reinforce that interpretation, those holding stereotypical views about Muslims were statistically more opposed to Syrian refugees than those who did not. This prompted me to look further into the relationship between such stereotypical views and evangelical identity in explaining attitudes toward Syrian refugees. The analysis is relevant in light of Christian nationalism, which promotes a national identity restricted to those who are native-born, Christian, and white, while actively ‘othering’ Muslim and non-white immigrants (for more, see Whitehead and Perry (2020)). Although Christian nationalism is not limited to any particular religious tradition, Shortle and Gaddie (2015, 440-41) note, “Evangelicals primarily, but not exclusively, subscribe to this religiously conflated version of national identity that makes anti-Muslim attitudes likely.”

I took advantage of the Karlson, Holm, and Breen method to assess whether the impact of religious tradition measures on refugee attitudes was mediated by Muslim stereotypes. Compared to the baseline category of Mainline Protestants, evangelicals were the only religious tradition for whom attitudes were significantly mediated by Muslim stereotypes. This means that although evangelicals were not unique in their opposition to Syrian refugees, they were distinctive in holding high levels of stereotypical views about Muslims, which made them more opposed to Syrian refugees in turn.

In the final stage of my analysis, I looked within the evangelical community to see whether there were variations in attitudes across demographic and socio-economic cleavages, and there were interesting differences within the tradition. The figure below is showing the effects of each row variable – points on the right of zero (the red vertical line) suggest the variable increases opposition to the refugees and points on the left suggest more of the row variable increases support for them. For example, all else equal, women were significantly less opposed to Syrian refugees than their male peers. Similarly, younger evangelicals and those with higher educational qualifications held more agreeable attitudes. This implies that it is problematic to treat lay evangelicals as an undifferentiated whole. In fact, certain groups within the tradition remain more aligned with the progressive position of the church leadership.

In sum, this research has three main takeaways. First, although it is misleading to single out evangelicals for their aversion to Syrian refugees, it is important to acknowledge the pervasiveness of strong Muslim stereotypes within large sections of the evangelical community. Therefore, if the church elite is capable of mobilizing the laity in favor of refugees, they must combine their pro-immigration rhetoric with an equal emphasis on inter-faith understanding to mitigate prejudice against Islam. Finally, evangelicals must not be viewed as a monolithic category for the purposes of this issue. Doing so risks drowning the voices of those with more favorable attitudes.

Oindrila Roy is an Associate Professor of International Relations at Cottey College.

Image Credit: The cover image “Little Amal at the New York Public Library” was retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. The image was produced by Jim.henderson, CC BY 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons ()

Image Note: The title image shows little Amal visiting New York City in 2022. Amal is a giant puppet representing a 10-year-old Syrian refugee. Amal has traveled across the world to raise awareness about the human rights of refugees. More information on Amal is available here.