By Zachary Broeren (Vanderbilt University) and Paul A. Djupe (Denison University)

[image credit: Getty]

As the four Trump trials and the 2024 presidential election race to their verdicts, his voters are faced with a choice: support a man who has purportedly broken the law or reject Trump. At the core of this decision is the importance of the equal application of the rule of law – the idea that no one, not even former presidents, should be able to break the law and get away with it.

However, a subset of his base – Christian nationalists – may be particularly susceptible to unequal applications of the rule of law. Christian nationalism, the intent to obtain and keep power to serve the interests and implement the practices of the Christian ingroup, may have a weaker attachment to the rule of law because of their strong group attachments.

At the core of most research efforts, those with strong ingroup love and outgroup hate would be loathe to share power and would be likely to treat in and outgroups unequally. While many policy positions correlated with Christian nationalism are more punitive, less generous, and just generally more exclusive toward groups Christian nationalists do not like, that evidence does not quite address the rule of law. For instance, in the research about attitudes about punishments and harsh policing, one of the survey questions asks for agreement with the statement, “Police officers in the United States shoot blacks more often because they are more violent than whites.” This does not quite capture whether Blacks should be treated differently just because they are an outgroup, but that Christian nationalism is associated with the (racist) belief that Blacks are more violent. We need to assess evidence that, given equal conditions, Christian nationalism is associated with treating the outgroup distinctly merely because of that designation. And what better way to assess this kind of treatment than to ask people how they would treat others if they were in a position of authority.

If afforded the opportunity, would Christian nationalists unequally treat ingroup and outgroup members?

In our research published in Politics & Religion (open access!), we attempted to answer this question utilizing a survey experiment conducted in Fall 2021, in which we effectively deputized members of the public. Each respondent in the survey received one of the four following statements beginning with the wording: “A man in his car is pulled over for speeding. He explains to the officer that

- he was speeding because he is late for worship at his Baptist church [Baptist].

- kickoff for a huge college football rivalry is soon and he needs to buy a 6 pack before it begins [Football].

- he was speeding because he is late for Jummah prayers at his Mosque [Muslim].

- he was speeding because he is running late for a lecture on veganism he has been looking forward to [Vegan].”

Respondents were then asked whether they would give the man a ticket or a warning. The descriptive results in Figure 1 show that respondents are much more likely to give a ticket than a warning, with the two non-religious treatments receiving the highest ticketing rates and the two religious groups receiving the highest warning rates.

Figure 1 – Who Gets a Ticket vs a Warning?

Source: September 2021 Survey.

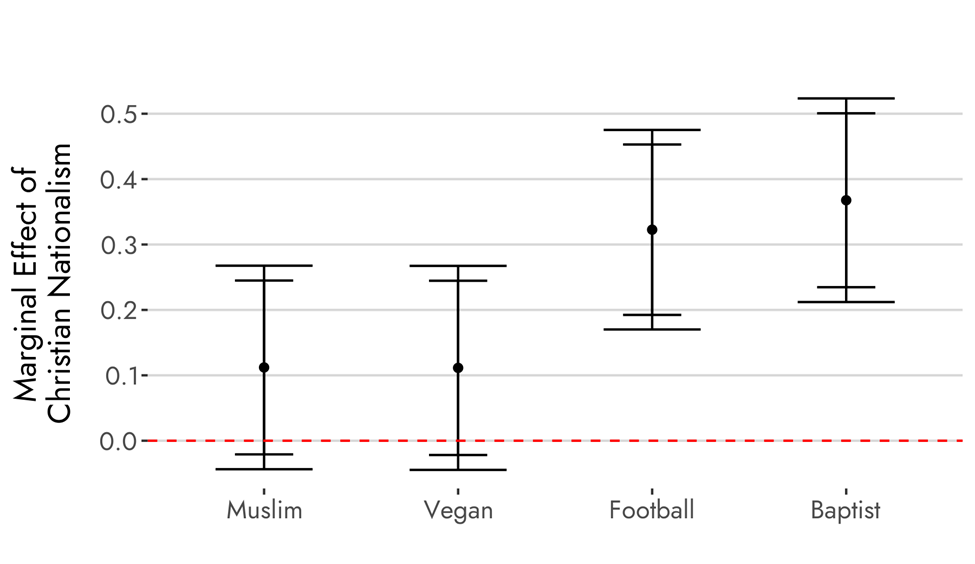

While there may be some differences between treatments for the whole sample, it doesn’t get at what we care about: are there differences between those who subscribe to Christian nationalism and those who don’t? For both the football and the Baptist treatment, the stereotypical “ingroup” treatments for Christian nationalists, Christian nationalists were 30-40% more likely to give a warning than non-Christian nationalists. However, Christian nationalists gave warnings to the outgroups – the Vegan and Muslim – at statistically indistinguishable rates from non-Christian nationalists. This was surprising to us: We see ingroup love demonstrated here, but where is the outgroup hate?

Figure 2 – Ingroups are Most Likely to get a Warning from Christian Nationalists; No Effect on Outgroups (a positive number signals a higher chance of a warning)

An important mobilizing factor driving the public implications of Christian nationalism is the element of victimhood, threat, and persecution. Whether it is the great replacement theory, election denialism, demonic Democrats, or the woke media silencing conservative voices, there is always a way that Christian nationalism can find a way to justify the actions it undertakes in the name of self-defense. We explore this in our analysis by testing the effect of a variable developed by Djupe, Lewis, and Sokhey in The Full Armor of God called “Belief in Christian Persecution.” This variable is an index of four questions that gauges whether or not one believes that Democrats are out to get them – whether they would ban the Bible, eliminate their religious freedom, make them pay for others abortions, and take their guns. This is verbatim the rhetoric employed in the run-up to the 2020 election.

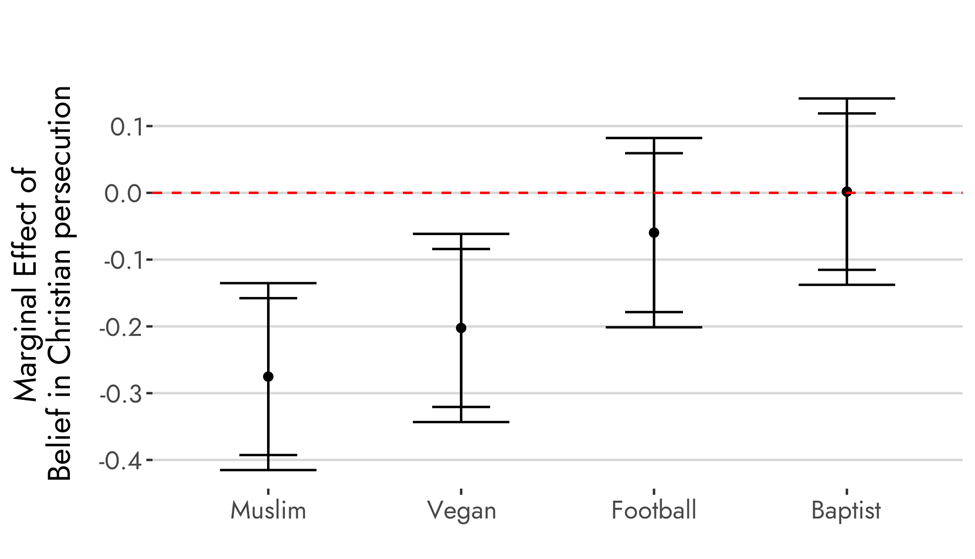

The pattern is reversed from what we saw above. Here the effect of belief in Christian persecution drives up ticketing the Vegan and Muslim outgroups, while Christian persecution had no effect on the ingroup Football fan or the Baptist. Those who believe in Christian persecution were 30% more likely to give the Muslim and 20% more likely to give the Vegan a ticket.

Figure 3 – Outgroups Less Likely to get a Warning When People Believe in Christian Persecution; No Effect on Ingroups (a positive number signals a higher chance of a warning; negative means a higher chance of a ticket)

The experiment helps us learn several things about Christian nationalism. First, the worldview is linked with violations of the rule of law along the lines of group identity. We (the academic community) already suspected this was the case because the correlational evidence is essentially overwhelming and consistent. However, a causal connection is always valuable to backstop the general argument. But the worldview also appears not to guarantee outgroup denigration. It appears necessary to believe that threats are real and imminent. Of course that is the case in recent history, but these threats were not always present and hence the highly exclusive, prejudicial stance of Christian nationalism may not have been a constant in US history and may not continue to be so into the future. Of course, if idea entrepreneurs continue to be successful in convincing believers that the threat is real, then it will likely continue. But, at least in theory, affirmative Christian nationalism that reifies the ingroup is separable from negative Christian persecution that is trained on outgroups. For academics and pollsters, our evidence suggests that it is especially important to monitor threat/persecution into the future to know if Christian nationalism is about to shake the foundations of American politics.

Zachary D. Broeren is a PhD student in the political science department at Vanderbilt University. His research lies in the American Political Behavior subfield, with a focus on political information, political psychology, public opinion, participation, and religion and politics. He’s on TwiX.

Professor Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found on his website and on TwiX.