By Paul A. Djupe (Denison University) and Jacob R. Neiheisel (SUNY-Buffalo)

“2024 is our final battle.” “The Seal is broken by what they’ve done…” “the sick political class that hates our country.” “There is a demonic portal above the White House.” “The Satanic Elites have a plan, but so do we.” The vernacular of politics in the U.S. in the Trump era is easy to dismiss as a hyperbolic and dark perspective consonant with Trump’s vision of American carnage from his inaugural address. But we believe it is more than that and marks a sharp break from the kinds of rhetoric used by Republican elites in the past. Not just expressive imagery, such language is an explicit call out to a sizable constituency that believes that these notions are true and happening all around us.

We call this worldview apocalypticism. ‘Apocalypse’ simply means revelation or prophecy, but refers to the Book of Revelation in the Bible, which lays out a horrifically violent end of the world and final judgment. In parallel with the biblical version, modern apocalyptics believe in embodied, demonic evil, battles in the spiritual and earthly realms, that Christian persecution is rampant, and that believers have a direct line to channel God’s vision and power through prophecy.

So when commentators reflect on the overwhelming degree to which evangelicals support Donald Trump, we believe they are missing the driving force behind that support and why some evangelicals do not support Trump. To be sure, apocalypticism is not the only fault line running through evangelicalism as many Latino and African-American evangelicals (and non-white evangelicals more generally) likely don’t share the same political affinities as their white co-religionists. But we think that an apocalyptic worldview strongly differentiates evangelicals who support Trump and those who do not. And in this post we will present evidence from a survey that we conducted in October 2022 to showcase how apocalypticism correlates with support for Trump among evangelicals and non-evangelicals alike.

Splits over social and political issues are a prominent feature of American Christianity – and have been since at least the American Civil War. Disagreements about theological matters have also divided evangelicals over the years. For instance, there has long been a simmering rift between those who hew to a vision of the “end times” that sees the faithful being whisked away (“raptured”) from a troubled world before those who are “left behind” are made to endure a period of great suffering versus those who believe that they, too, will have to witness the horrors of the tribulation period. In the past, different views of the end had political consequences, with many evangelicals disengaged from politics in the belief that such efforts are tantamount to “polishing the brass on the Titanic.”

Since at least the 1980s, however, more and more evangelicals have come to believe that they will witness something of a “humanist tribulation,” even if they are similarly convinced that they will “meet the Lord in the air” (1 Thessalonians 4:17) prior to the onset of an extended period of truly horrible events. As Daniel Hummel notes in his excellent book on the subject, “pop” visions of the end times have overtaken the sometimes complex, nuanced theological versions of the same. And, as one of us pointed out in a previous post, there is evidence that the traditional schools of thought surrounding the end times are breaking down into widespread agreement among evangelicals on many points that used to divide them. The new schism is between those who hold an apocalyptic worldview and those who do not.

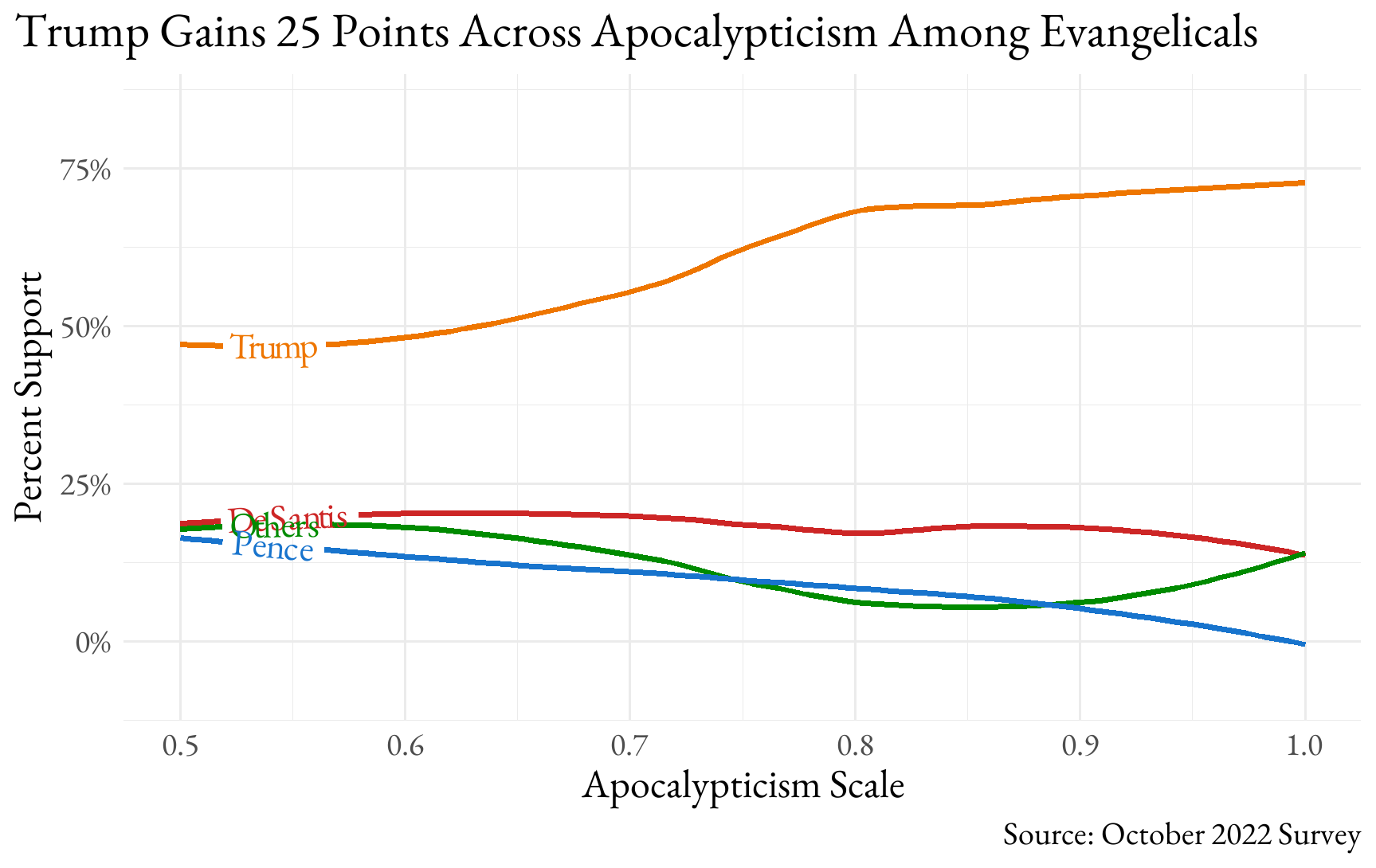

Is there evidence that apocalypticism shapes support for Trump? We draw on data from 2,100 Republicans surveyed in October 2022 using a survey question that asked for responses for those planning to participate in the Republican nomination contests. The figure below dramatically shows support for potential Republican candidates shifts as adherence to an apocalyptic worldview (as we define it) increases. Just 21 percent of non-apocalyptics support Trump, a figure which grows to about 80 percent among the very most apocalyptic. It is no surprise that Donald Trump is the only beneficiary, as support for Ron DeSantis, Mike Pence, and other Republican presidential hopefuls declines as apocalypticism increases.

Just because support for Trump is highly correlated with apocalypticism, however, does not mean that the other candidates were disliked among adherents to the apocalyptic worldview. Indeed, feelings toward DeSantis double in warmth across the apocalypticism scale. Not surprisingly, feelings toward Trump also rise as apocalypticism increases, consistently outpaced only by feelings toward “Christians” as a whole. Equally unsurprising is that feelings toward Biden start low among this sample and continue to crater as apocalypticism increases.

One potential criticism of our analysis is that it may disguise the effect of evangelicalism. It is true that evangelicals score more highly on our measure, though we find commitment to apocalyptic worldviews across the religious spectrum in the US. Still, the only response is to look for a relationship between apocalypticism and vote support among evangelicals – is there still evidence of a faultline caused by apocalypticism?

Among just evangelical Republicans, support for Trump starts high (~50 percent) and rises precipitously to about 75 percent as apocalypticism increases. DeSantis, Pence, and others exhibit much lower support and are essentially indistinguishable from each other. Key, in our view, however, is the fact that support for these (former) GOP hopefuls remains essentially flat as apocalypticism increases; Pence – perhaps the most overtly religious candidate at one point in the 2024 Republican field – sees a slight decline in support throughout the observable range of apocalypticism.

It is important to point out that our x-axis starts at roughly the midpoint of the apocalypticism scale. This is because there are almost no evangelicals who score below .5 on our measure of apocalypticism, indicating a tight tether between evangelical Christianity and an apocalyptic worldview. Some of this is surely doctrinal in nature, as many evangelicals believe that embodied evil walks on Earth – one component of our broader apocalypticism measure. Other elements of our apocalypticism battery, however, go well beyond simple adherence to matters of faith. For instance, while many evangelicals believe that Christ will return one day, we asked respondents whether they believe that we are currently living in the end times now.

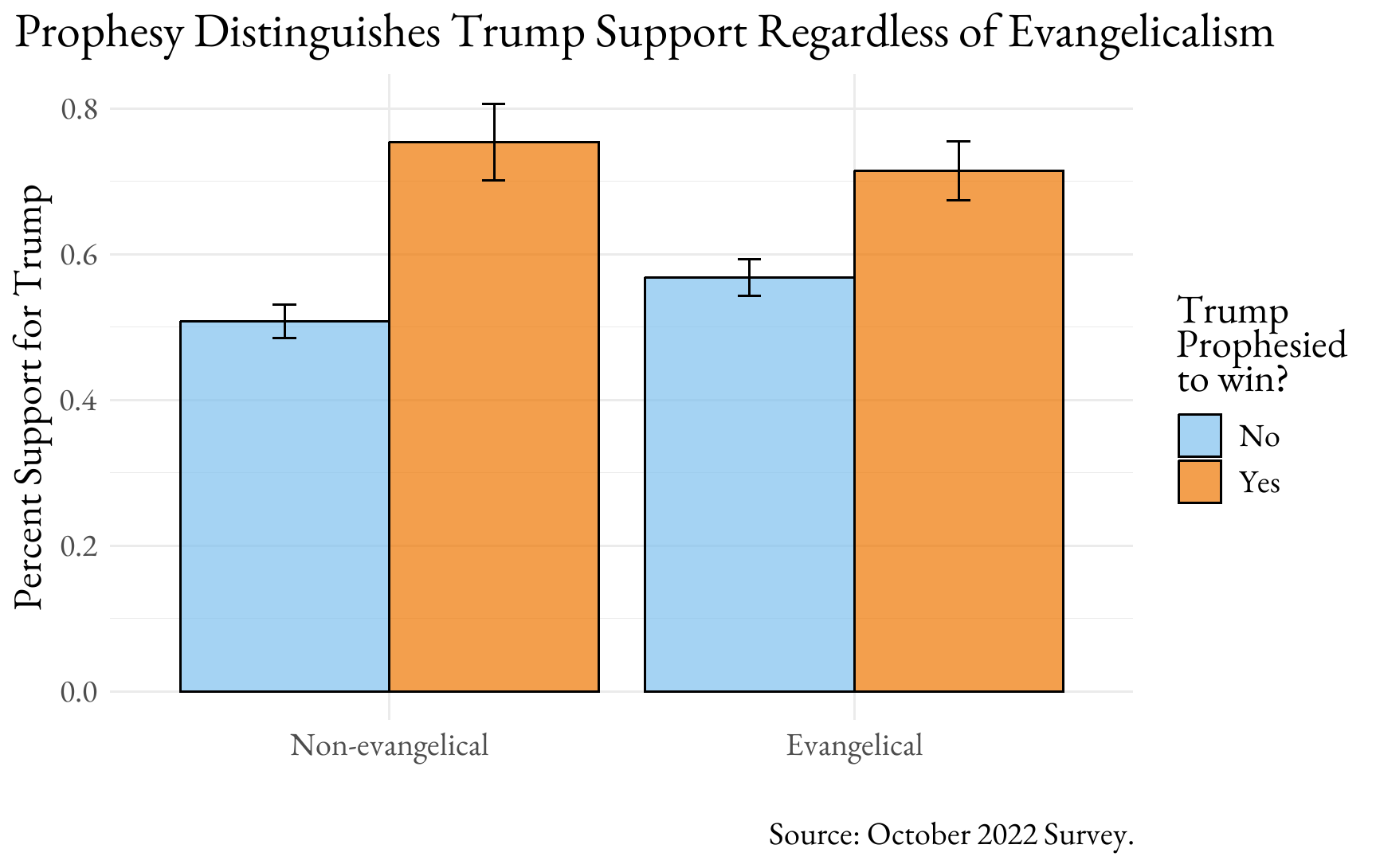

As should be clear at this point, the available evidence suggests that there is a political rift within American evangelicalism that transcends race and divides partisans. Support for Trump increases as apocalypticism rises. Drilling down to some of apocalypticism’s constituent components may likewise shed light on the differences that exist between those who exhibit high levels of support for Trump and those who are more reluctant to embrace the former president. Prophecy belief is a necessary part of the apocalyptic worldview, and we asked respondents whether they believe that prophecy points to Trump’s triumphant return to the political arena. Agreement with this item (18 percent of the sample agreed; 24 percent of evangelicals, 12 percent of non-evangelicals) discriminates with respect to support for Trump among evangelicals and non-evangelicals alike. Those who agree that Trump’s future victory has been prophesied are more likely to express support for the former president, though the causal ordering here is surely up for debate. It certainly could be the case that those who like Trump have convinced themselves that their belief system points with certainty to something of a second coming of sorts.

A similar divide appears on the question of whether the respondent believes that deteriorating cities are a sign of growing evil. Those who engage in end times thinking are often trained to see contemporary events of all sorts as signs of an impending doomsday. In recent years everything from COVID-19 to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been bandied about in certain circles as a portent that the end of days is on the horizon. Moral decline, especially set in cities, has consistently been viewed as one such sign of the coming apocalypse so it should come as no surprise that agreement with such a belief is associated with greater support for Trump among both evangelicals and non-evangelicals.

Taken together, these patterns in the data suggest that an affinity for Trump is about more than just the intersection of race and evangelical affiliation among Republicans. Rather, we contend that another force looms large as a determinant of support for Trump that connects with explicit rhetoric that resonates with a subset of the faithful. This force, too, is religious in extraction, but unlike measures of religious belonging, this one is firmly rooted in a particular set of religious beliefs.

Recent scholarship pitched at the nexus of religion and politics has argued for the primacy of politics over religion as a predictor of political behavior, with partisanship acting as the “master identity” according to one analyst. And while we do not deny that politics can shape religion in many discrete ways (indeed, much of our own research supports this contention), we think that it is high time that the scholarly community recommits itself to exploring the ways in which religious belief helps to explain political phenomena without reference to crude distinctions based on denominational boundaries – boundaries that predict little without also conditioning on race and other factors. Instead, careful theorizing about the ways in which certain sets of long-standing American religious beliefs translate into other arenas may help us to forge a better understanding between faith and politics, including support for Donald Trump.

Jake Neiheisel is an associate professor of Political Science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY (UB) and a faculty affiliate with the Philosophy, Politics, and Economics program at UB.

Professor Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found on his website and on TwiX.