By Jacob R. Neiheisel and Paul A. Djupe

In the early morning hours of June 14th, a Minnesota lawmaker and her husband were shot and killed in what Minnesota Governor Tim Walz described as “what appears to be a politically motivated assassination.” That same morning, another state lawmaker and his spouse were also shot and seriously wounded by what is believed to have been the same assailant. According to authorities, the suspected shooter targeted other elected officials as well, and a “hit list” of mostly Democratic officials along with abortion providers and pro-choice advocates was discovered in his car.

As often happens in the aftermath of such incidents, reporters began to dig into the suspected gunman’s personal life in an effort to unearth something that might be seen as a motive for his heinous acts. A number of outlets (including Stephanie McCrummen for The Atlantic and David French in the New York Times, among others) quickly seized upon the suspect’s religious background as one possible factor that served to drive his actions. It turns out that the shooter attended the Christ for the Nations Institute (CfNI) in Dallas, Texas. The CfNI describes itself simply as a “Spirit-filled Bible school.” For close observers of the ever-shifting global religious landscape, however, this seemingly straightforward description signals a connection with the independent Charismatic movement.

Indeed, a piece published by Religion News Service points out that the school is connected with many of the luminaries of the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR) – a movement that the article defines as consisting “of independent charismatic apostles and prophets that seeks to have Christians dominate all elements of society, including the government.” Those affiliated with the NAR often believe in the necessity of “spiritual warfare” and frequently articulate a vision for the future that can sound, to many observers, akin to Christian nationalism.

While it is unclear at this time whether the accused shooter was directly motivated by NAR beliefs, religious studies scholar Matthew Taylor is quoted as saying in an article in Baptist News Global that the accused shooter “is somebody who has dipped into the world that surrounds the New Apostolic Reformation, has spent some time in charismatic leadership circles, has some ties in that world, and that seems to have played some role in his radicalization.” Indeed, a video of the accused shooter speaking to a group of evangelicals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo does show him using a familiar language – that of “the enemy” and demonic possession – to describe those who he believes to lead people astray (the alleged perpetrator takes the stage at around the 36 minute mark in the video).

Just how widespread such commitments are among the public are little understood and are a point of some contention in both scholarly and popular circles. One of us (Djupe) was recently interviewed by Stephanie McCrummen from The Atlantic to offer the best available information on the number of Americans who might express an affinity for the worldview articulated by adherents to the NAR. This is difficult because believers are not identifiers – they don’t call themselves the New Apostolic Reformation and instead work to spread the belief system without the limitation of labels. The belief system is broadly charismatic with a collection of memes leaders hope to promote that have included the 7 mountain mandate, the billion soul harvest, and many more. As covered in McCrummen’s article and elaborated here, Djupe found that 40 percent of self-identified Christians in January 2024 (42 percent in October 2024) agreed that “God wants Christians to stand atop the ‘7 Mountains of Society’ (government, education, business, etc.).”

Though less than a majority of believers in the United States, a surprising number of Americans appear to express common cause with the NAR. Apart from the number of individuals who might be considered to be part of the NAR (or travel in such circles, as the accused shooter appears to have), a growing body of evidence also points at the religious “fringe” having a profound impact on the direction of the center and, as such, can hardly be understood as being marginal at all. As Taylor notes in his recent book The Violent Take It by Force, “the rhetoric of spiritual violence stokes real-world violence. You can only proclaim that a group of people or a political party is filled with demons for so long before someone decides that those demonic vessels must actually be physically attacked” (2023, 109).

This is not the message that is being offered by officials representing the Christ for the Nations Institute, however. In a statement released in the aftermath of the shooting, school officials explained the institution’s views by quoting Ephesians 6:12, writing that “‘we do not fight against flesh and blood enemies, but against evil rulers and authorities of the unseen world…against evil spirits in the heavenly places.’ Christ For The Nations does not believe in, defend or support violence against human beings in any form.” It isn’t at all clear at all that rank-and-file believers always adhere to the distinction between spiritual violence and physical violence, however, and it is worth investigating how a belief in spiritual warfare tracks with support for more earthly conquests and pursuits.

We have been studying spiritual warfare as part of a broader project trained on apocalypticism–a belief system that holds that battles are happening now, that Christians are actively being persecuted, and that the end of days is near. In our data, 50 percent of Christians in both January and October 2024 data agree that “The church should organize campaigns of spiritual warfare and prayer to displace high-level demons.” If this is the analog to the spiritual warfare that CfNI is talking about, then we can assess what other beliefs and attitudes it is connected to.

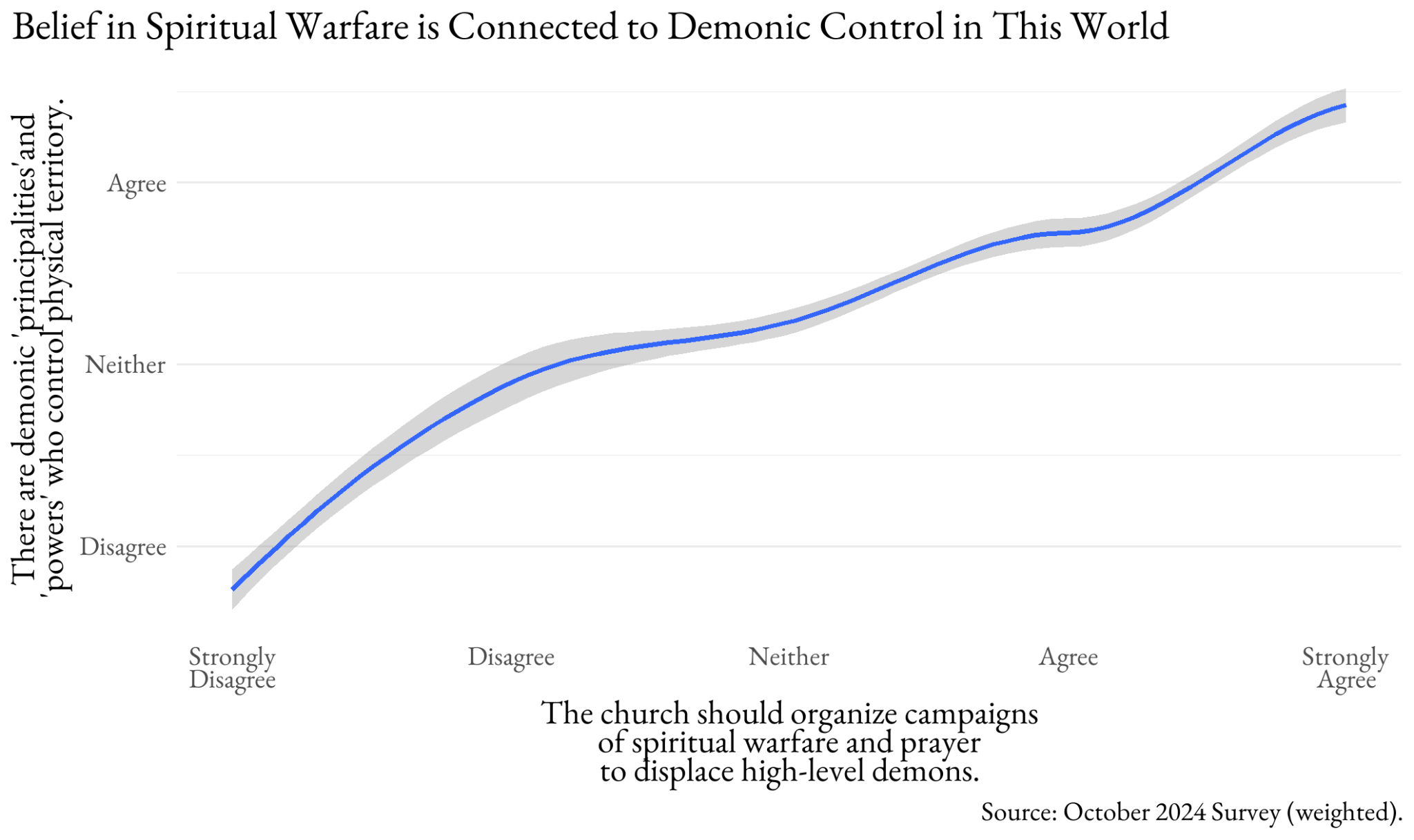

First, we wanted to see if believers in spiritual warfare connect those beliefs to physical places (rather than taking place in the spiritual realm). Another NAR-connected meme that we asked about is that there are demonic principalities and powers that control physical territory. The figure below shows this tight relationship (correlation of r=.73). If you agree with the notion of fighting spiritual warfare, you are quite likely to perceive actual demons controlling Los Angeles (and of course other places).

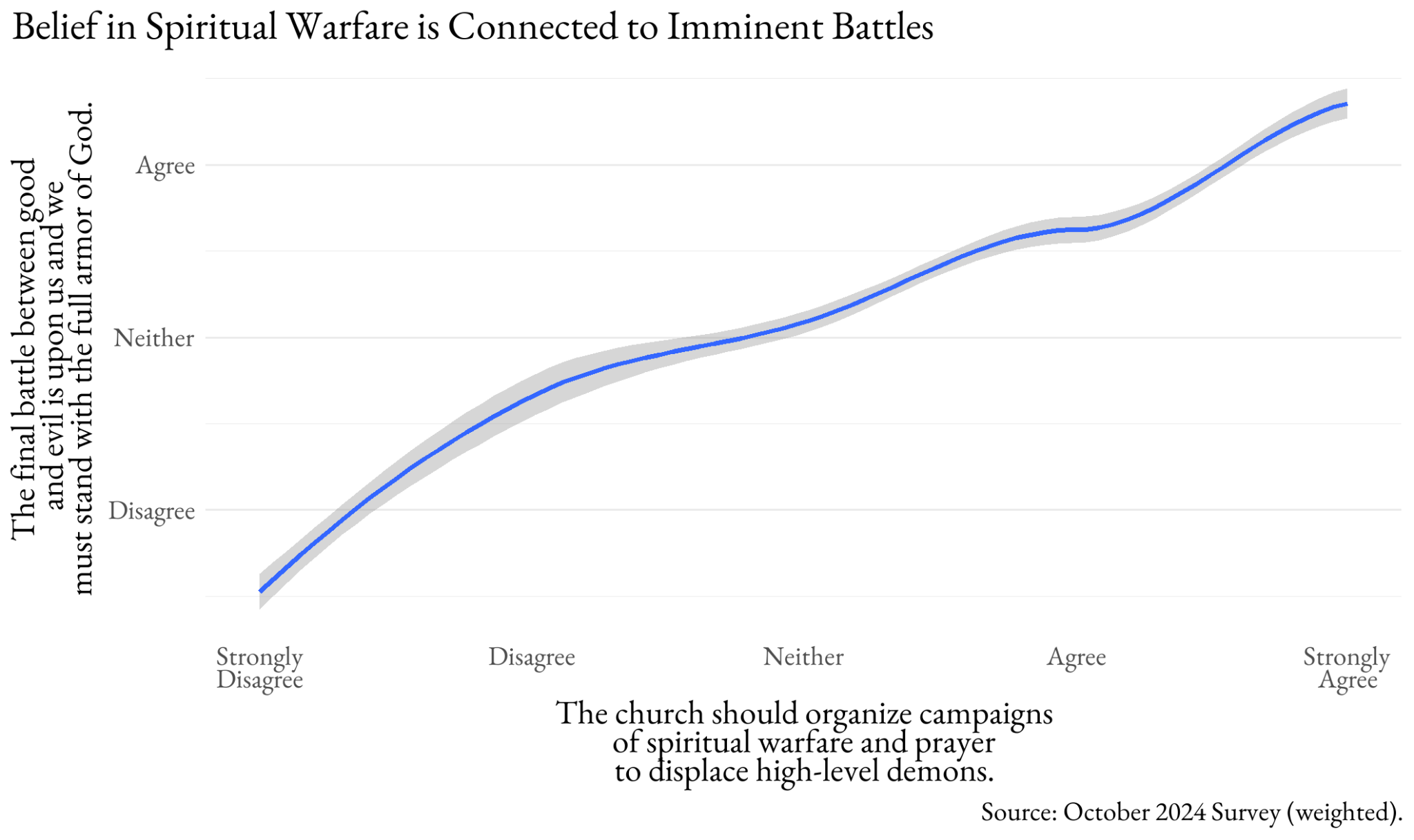

As we noted above, others have made the claim that “spiritual” is not doing a lot of work to distinguish it from physical warfare. Can we find a link between pursuing spiritual warfare and preparing for battle in this world? The figure below highlights another strong relationship between those notions – as support for spiritual warfare increases, so does the belief that the final battle is here and they will have to don the full armor of God. That is perhaps the best single measure of an apocalyptic perspective we have (there is an equally strong relationship with a more comprehensive measure of apocalypticism as well).

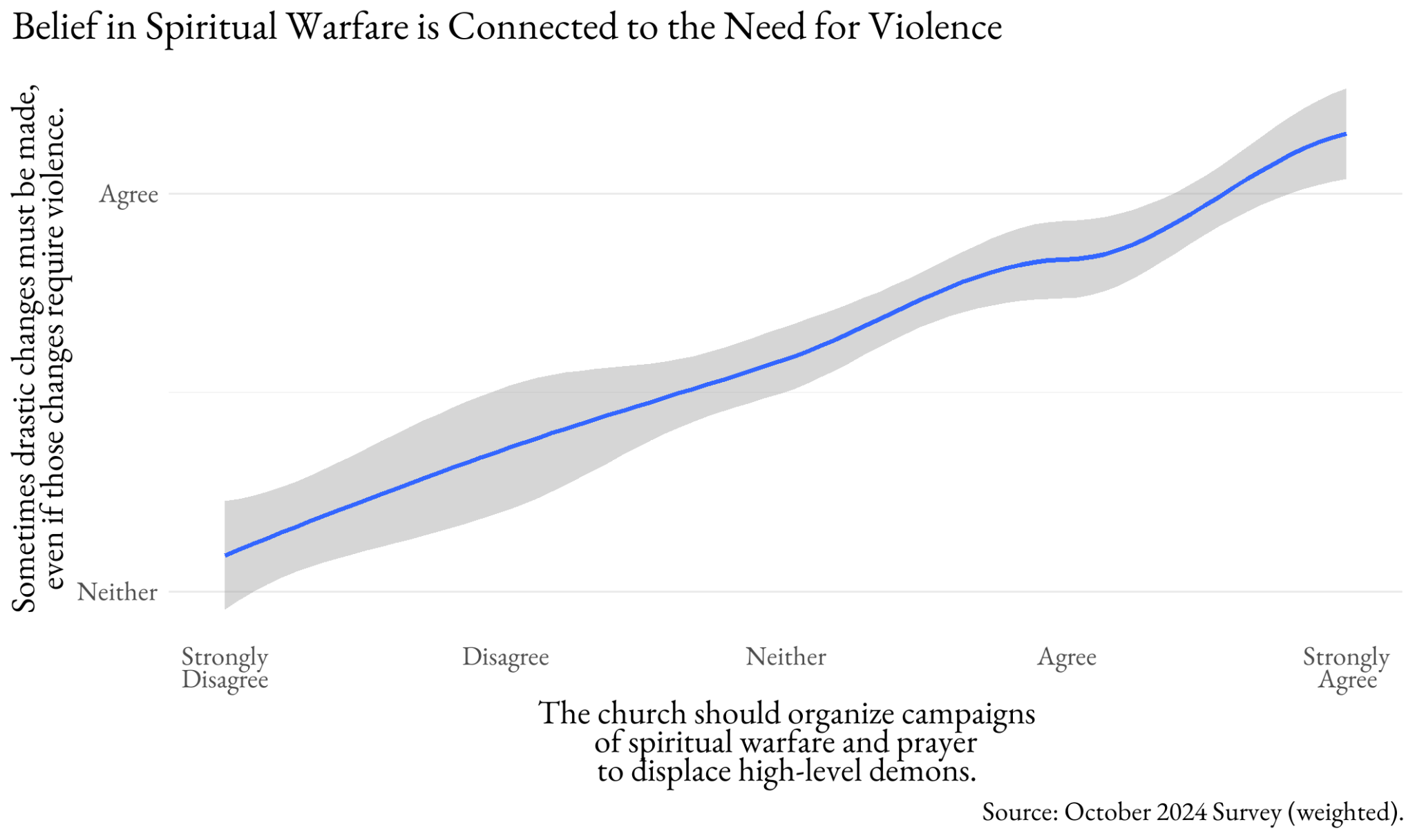

The weakness of that apocalyptic measure is that it is not explicitly this worldly. Fortunately we also have access to a secular measure that captures how acceptable it is to use violence: “Sometimes drastic changes must be made, even if those changes require violence.” The relationship is weaker (r=.26), but spiritual warfare is linked to a greater acceptance of turning to violence to achieve drastic changes. Clearly not every believer in spiritual warfare takes the next step to seeking violence to achieve change, but it is much more common for them than it is among others.

Logically, CfNI school officials could be right that spiritual warfare that they teach is confined to the “unseen,” cosmic realm. But that border is a porous one, especially when related figures up to and including high-ranking public figures are arguing that other public officials, party identifiers, and even whole regions of the earth are under the control of demons. Those beliefs are reinforced by apocalyptic narratives that society is declining, cities are crumbling and filled with violence, Christians are being widely persecuted, governments are corrupt, and much more. Under those invented circumstances, it is no surprise that someone who is trained in spiritual warfare would turn his gaze to the earthly realm and try to aid the heavenly host with his arsenal. Indeed, some media outlets are reporting that the accused gunman was a “prepper.” That is, he was someone who engaged in efforts at physically preparing for some kind of impending disaster. In our previous research we have found that preparedness behavior is linked with apocalypticism – a connection that seems radically out of place if the eventualities that one is concerned about are confined to the spiritual realm. What this says to us is that there are some believers–and there have always been some – who are hardly content to understand cosmic battles as elaborate metaphors alone and expect to experience a confrontation with the forces of evil in the here and now.

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of political science and faculty affiliate with the philosophy, politics, and economics program at the University at Buffalo, SUNY.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website or on Bluesky.