By Paul A. Djupe and Jacob R. Neiheisel

On September 10, 2025, activist Charlie Kirk was assassinated at a Turning Point event at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah. In our view, all political violence is tragic and should be universally condemned. That is no less true for someone who argued that we needed to accept the violent consequences of gun access. But what is interesting about Kirk is the role he played in the conservative movement, which continues to be contested. Whether he was unifying is perhaps less important now than whether his image and legacy is unifying. We’ll take a look here with some new data.

In a December 12, 2025 email advertising his conversation about Kirk with Matt Walsh, Tucker Carlson argued that, “People might not have realized it when he was alive, but Charlie was the glue that held the conservative movement together. His abrupt departure left a void that’s proven impossible to fill. We’re all feeling the effects.” Carlson’s view would prove prescient when, just a week later, speakers, including Carlson, would take potshots at each other at a TPUSA “America Fest” event. Having just watched The Return (about Odysseus’s return to Ithaca – it’s not a great movie), it’s hard not to see this TPUSA event as jockeying over who would inherit the TPUSA kirkdom.

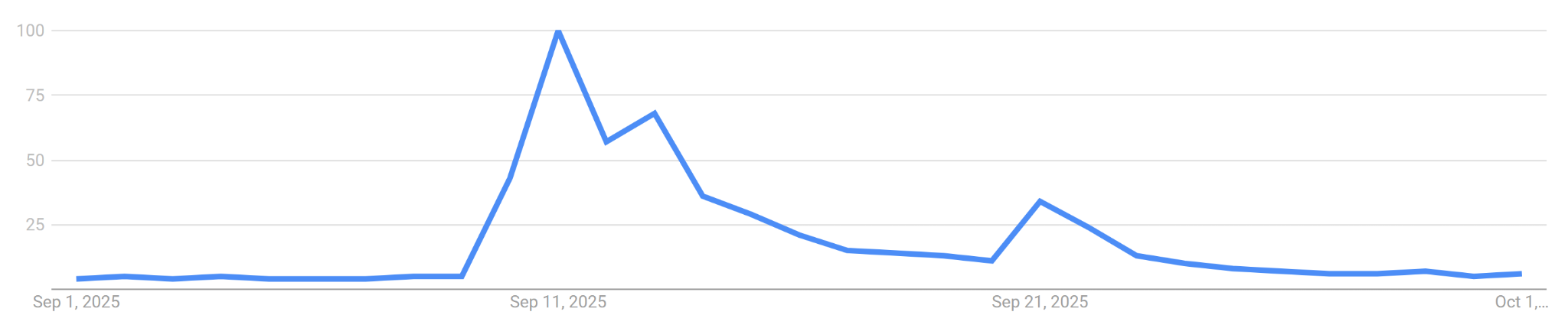

If Kirk can be disunifying through his absence, we’re more intrigued by the effects on unity of his image as a Christian martyr. A martyr is a person killed for their beliefs and Kirk was tagged with that label in the aftermath of his murder. Google search trends for “martyr” right after his death highlight the immediate, striking association (which was higher in highly conservative Christian states like South Dakota and Oklahoma).

At that same December TPUSA rally in which Carlson and other prominent figures on the right openly jousted with each other, the argument for Kirk’s martyrdom was on full display as a way to “radicalize” the young attendees according to Professor Christina Littlefield of Pepperdine. This is not a new pattern, with deep tracks laid since Biblical times seen in the warning in 2 Timothy 3:12 that “Indeed, all who desire to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted.” Many have noted how extensively Christians believe that they are persecuted in the US, much more so than racial minorities or Muslims finds PRRI. For instance, Alan Noble argued in The Atlantic that conservative Christians have a “Christian persecution complex” in which “persecution has an allure” even when it is fictional. As we argued in The Full Armor of God, “[T]he myth of martyrdom may help produce new generations of culture warriors who expect persecution and accept the need for violence.” And, for at least some of these culture warriors, any opposition that they encounter can be framed as anti-Christian persecution.

In our December 2025 survey of 2,000 American adults conducted through Verasight (and weighted), we asked a number of questions about Kirk, including whether respondents agreed or disagreed that “Charlie Kirk is a Christian martyr.” Overall in the sample, 31 percent agreed (or strongly agreed) that he is a martyr. The figure below shows that partisans are deeply divided on this question – only 12 percent of Democrats agreed compared to 58 percent of Republicans. But the figure also shows that Republicans are divided with 24 points separating Republican leaners from strong Republicans.

Perhaps it’s no surprise to see Kirk valued among strong Republicans given his explicit role as TPUSA head, the purpose of which was to mobilize young Republicans. But that framing undersells the religious component, which may in fact be divisive, even among Republicans. And Kirk’s legacy was not just about religion, which he came to later in his short career. His brand involved antagonism to “woke” higher education, which he framed as the promotion of free speech. In any event, looking deeper into the data, we might find a range of intra-partisan divides surrounding Kirk’s martyrdom.

In the following figure, we compare feelings (0=cold, 100=warm) toward a range of figures split into groups who agree that Kirk is a Christian martyr (orange) versus those who do not (blue). It is sorted by the size of the gap between the two groups. The largest gap is over Kirk himself, followed by a 22 point gap over ICE and 17 point gap over Trump. Notably, those who agree Kirk is a martyr feel warmer toward Kirk over Trump.

What’s next is particularly interesting – those not on board with Kirk’s martyrdom feel warmer toward colleges and universities. Not that they are big fans – they feel about the same about universities as they do toward ICE. But given Kirk’s schtick, the gap is notable. It’s also worth noting that those not on board with martyrdom are less polarized, feeling a bit less warm toward Republicans and a bit warmer toward Democrats. Kirk was a polarization agent, so it makes sense to see this reflected in the data.

There are only small gaps in warmth toward Christians of various configurations. There is a 10 point gap in feelings toward Christians (both quite warm), but the gaps over Christian fundamentalists and Christian nationalists are smaller and together lean cold. Even among Kirk loyalists, those explicitly labeled Christian nationalists aren’t warmly received.

In life, Kirk may have been a unifying force within the conservative movement. Though known initially as simply an advocate for free markets and other core conservative ideas, Kirk would later turn more overtly toward a religious conservative outlook, serving as something of a bridge between different elements of Trump’s base.

In death, it seems, Kirk’s legacy is divided between those who see him as a martyr and those who reject this view, leaving a visible faultline among Republicans that can be seen in their varying stances toward a wide array of politically-salient groups and figures. Though we can only speculate given the available evidence, it seems likely that those who see Kirk as a Christian martyr will continue to be true believers in Trump himself and be more on board with demonizing frequent targets of Trump’s administration (e.g., immigrants, universities), even among otherwise similarly situated Republicans. How this rift continues to play out on the political right will be something to watch closely in the coming months and years.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website, on Bluesky, and on Threads.

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY and is coauthor of the forthcoming The Politics of the End: Apocalypticism in America (NYU Press).

[like] R. Brown reacted to your message: ________________________________

LikeLike