Paul A. Djupe, Jacob R. Neiheisel, and Anand E. Sokhey

We need to be able to talk to each other. Not just the people we agree with, but also the people who may see things from other perspectives. Without the ability or opportunity to talk across lines of difference, we risk our ability to learn about the world and our interests in it, to organize around our common goals, and to hold government and other institutions to account for their failures to deliver on their promises. Our decreased capacity for political talk in the face of diversity is an existential threat to a free society.

The efficacy of face-to-face engagement across lines of difference must be one of the most replicated findings in the social sciences. First documented empirically by Gordon Allport in 1954, the contact thesis is that working with diverse others on a common task will undercut prejudice against them. As one meta-analysis of 500 studies in 2006 by Pettigrew and Tropp found, “[C]ontact reduces prejudice (defined broadly) regardless of the rigor, measurement tools, design (i.e., experimental or non-experimental) or target out-group.” There are very few social forces that are as robust as this, able to stand up to incredibly broad scientific and real-world variation in experience.

But it’s hard to do democracy these days when Americans have different facts or no facts at all. There’s no motivation and no need to talk if groups of people have no idea there’s a problem. But democracy gets even harder when people believe, as charismatic religious figure Mario Murillo claimed, that “you are full of the devil if you vote for any Democrat…You are literally spitting on the grave of the apostles, if you in any way, shape, or form have anything to do with voting for [Democrats].” In one of his books, Murillo argues that Democrats “are not a political party. They are oppressors.” Murillo inhabits one part of a much larger group with deeply held religious views that make democracy impossible.

Our research, published open access in Social Science Quarterly using March 2023 survey data, examines how those with apocalyptic views respond to diversity in their social circles – that is, the contact thesis. We mean something particular when we reference apocalyptic views. Apocalypticism combines the belief that embodied evil exists on earth, that believers can channel God’s power, that the final battle between good and evil is happening or imminent, and that Christians are being persecuted. It may be no surprise that these beliefs constitute a particularly toxic worldview that leads to a wide variety of anti-democratic views and behaviors as we document in a forthcoming book The Politics of the End (NYU Press coming later this year).

What we’re concerned with here is how apocalyptics respond to the presence of diversity in their social circle, which we measured by asking, “Now please think of all of the people that you know well enough to stop and talk with for a moment if you ran into them on the street. How many of these people are you pretty certain have the following attributes?” The groups listed were Muslim, Jewish, Catholic, Evangelicals, and Atheists/agnostics and respondents could indicate they know from 0 to 10 people with these religious identities. The diversity measure runs from all acquaintances being from one group to an equal proportion being from each group in their circle.

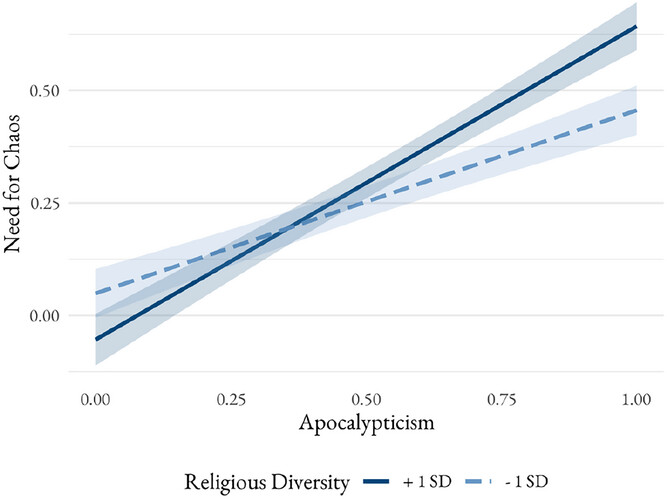

Based on our ongoing work, we expect that apocalypticism is linked to more extreme politics, and that exposure to diversity should intensify it. For apocalyptics, routine everyday encounters with diverse others offer stark reminders of the need for a power-sharing arrangement in a pluralist system that exposes them to evil and undermines the goal of establishing a Christian America. Apocalyptics eagerly anticipate a violent end to the existing world order – an end that will place themselves on top. As such, exposure to diversity likely serves to increase the desire among apocalyptics for the world as it is currently structured to come to a close. And that’s what the following figure shows – apocalyptics with higher than average social circle diversity have a greater “need for chaos” (agreement with “When I think about our political and social institutions, I cannot help thinking ‘just let them all burn.’”). On the flipside (lower left), exposure to diversity further weakens the need for chaos for those who are not apocalyptics, affirming the essence of the contact thesis.

Figure – Exposure to Religious Diversity Intensifies the Need for Chaos

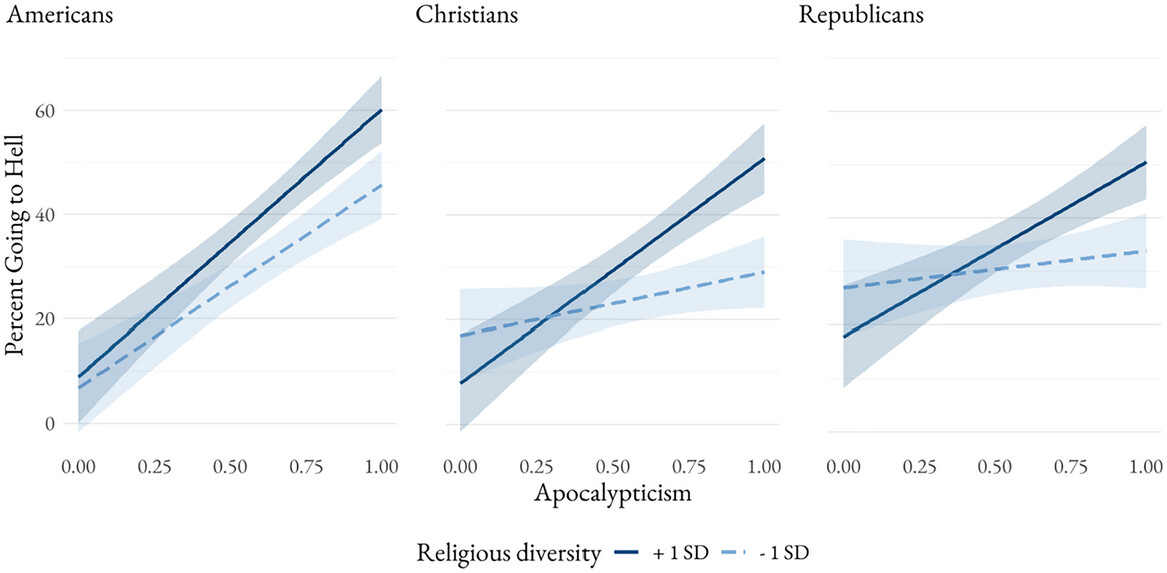

It’s not just that measure of political extremism – we repeat that analysis with a number of measures such as support for violence and for violent clashes with government officials. But one measure is particularly important for understanding just how apocalypticism is linked to extreme politics – they believe that almost everyone around them is evil, demonic even. One way we can tell is that we asked respondents what portion of various groups are destined for hell. And the following figure shows that an extraordinary number of Americans are damned according to apocalyptics exposed to more social diversity – three-fifths of Americans and half of Christians and Republicans. That estimate is notably lower among those in more homogeneous social circles (dashed line).

Figure – Exposure to Religious Diversity Drives up Apocalyptic Estimates of the Damned

We already know about the great freakout that many on the right have been having about the increasing diversity of the US, captured in the white nationalist Great Replacement Theory, in which immigration is an explicit tool for weakening the power of whites. Studies have already shown that telling people about increasing diversification of the US is linked to greater rates of reporting a Christian nationalist worldview. Two things are different about our work. First, we show the same dynamics playing out in real world settings beyond survey experiments, which is important confirmatory evidence. Second, these dynamics have been understood to have a political logic – if our numbers are decreasing, we need to rally around our political savior (Trump) who wants to arrest that decline. While that logic is not necessarily wrong, we also document a sincere religious motivation for a negative response to diversification.

More than simple in-outgroup differences, apocalyptic Americans see growing diversity as a sign that the devil’s minions are on the advance. Their very presence, even among “friends,” signals threat at every turn that is building toward a final confrontation. To the detriment of American democracy, that confrontation is now conflated with elections, with Donald Trump now floating the idea of cancelling the 2026 midterms, which builds upon his promise to “my beautiful Christians” that they will not have vote anymore after the 2024 election. For a sizable portion of Americans, sitting down to talk is not going to rescue civil society, but fuel its demise.

Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Bluesky.

Jacob R. Neiheisel is an associate professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY and is coauthor of the forthcoming The Politics of the End: Apocalypticism in America (NYU Press).

Anand Edward Sokhey is a professor of political science at the University of Colorado, where he directs the American Politics Research Lab and is a faculty fellow at the Institute of Behavioral Science. He studies political behavior and democratic functioning in the United States and is an associate editor at the Journal of Politics.