Elizabeth A. Oldmixon, University of North Texas

Photo credit: me

Clergy face high barriers to political engagement in Ireland. Like their American peers, they tend to have many of the characteristics associated with potent political activism, and they lead communities where people seek moral guidance and learn civic skills. Owing to Reformation politics, colonialism, and a history of oppressions, however, religious identities overlap considerably with national identities. Roman Catholicism emerged as the lodestar of Irish nationalism, and Protestantism became a symbol of British identity. This makes prophetic engagement across religious communities difficult.

Adding to this, Britain partitioned the six counties of Ulster from the rest of Ireland in 1920; the southern counties would eventually form an independent sovereign state, the Republic of Ireland, while the northern counties became Northern Ireland, a constituent member of the United Kingdom. Catholics comprised (and comprise) a substantial numerical majority in the Republic, and this allowed the Church to establish what Tom Inglis calls a “moral monopoly.” Priests did not need to engage politics because the very terms of political discourse were set by the Catholic Church. In Northern Ireland, by contrast, Catholics were and are numerically disadvantaged. As such, the Church never developed the sociocultural pre-eminence that it enjoyed in the south. Catholic priests were involved in republican politics, but by the 1970s many were skeptical of their actual influence and reluctant to engage. Adding to this, the need for engagement may have been mitigated by the mapping of religious identities onto the party system – someone was already carrying water for the Church.

The June 23, 2016, Brexit vote may disrupt the political milieu in the North, raising the possibility in some circles of a united Ireland, and drawing clergy into the public square. Why? While a slim majority of UK citizens voted to leave the European Union, nearly 56% of voters in Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. The Republic of Ireland has no plans to leave the EU, so in the wake of the vote, “Protestant unionists are queuing for Irish passports in Belfast and once quiet Catholic nationalists are openly campaigning for a united Ireland.” Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin went so far as to suggest that, “The remain vote may show people the need to rethink current arrangements. I hope it moves us towards majority support for unification, and if it does we should trigger a reunification referendum.”

For many in Northern Ireland and the Republic, EU membership is associated not only with economic modernization and stability, but also peace and security. Under the auspices of EU membership, free movement across the border has become the norm, and both countries enjoy greater cooperation with respect to trade and healthcare. This was codified by the Good Friday Agreements, which Gerry Adams argues were “founded on the democratic principle that the people of Ireland, North and South, should determine their own future.” Brexit threatens to undo all that, imposing a hard border, inflicting financial costs, and threatening to disrupt the peace in Northern Ireland.

The disruption may already be underway. The Independent reports that in order to secure the necessary votes in Parliament for her Brexit plan, Prime Minister Theresa May has had to make concessions to DUP (Democratic Unionist Party) MPs. Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland Martin McGuinness, pictured to the left, recently resigned his position, effectively ending the power-sharing agreement established by the Good Friday Agreements. McGuinness resigned in protest over alleged financial impropriety by a DUP legislator, but the larger concern is that May refuses to reign in DUP given that she needs their votes.

The disruption may already be underway. The Independent reports that in order to secure the necessary votes in Parliament for her Brexit plan, Prime Minister Theresa May has had to make concessions to DUP (Democratic Unionist Party) MPs. Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland Martin McGuinness, pictured to the left, recently resigned his position, effectively ending the power-sharing agreement established by the Good Friday Agreements. McGuinness resigned in protest over alleged financial impropriety by a DUP legislator, but the larger concern is that May refuses to reign in DUP given that she needs their votes.

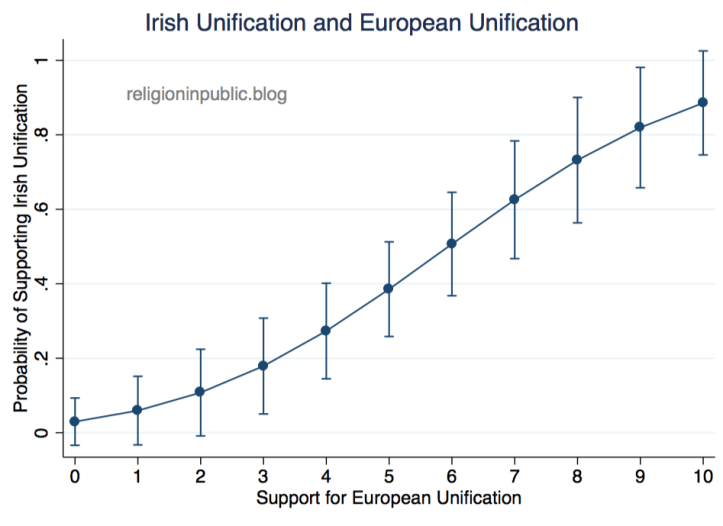

What role might clergy play in these developments? The “remain” vote crosscut communities, creating the possibility of coalition building on the future of Northern Ireland’s constitutional status. Leadership opportunities for clergy emerge as the faithful sort themselves on this issue. It is interesting to consider, then, clergy attitudes on the question of Irish unification. To the best of my knowledge, there are no post-Brexit clergy survey data on this issue. However, Brian Calfano and I have published a series of articles and a book on clergy in Ireland (here and here with Jane Suiter, and here with Melissa Michelson). The 2011 iteration of our original survey included a question on clergy preferences for the long-term future of Northern Ireland. The results are provided in the figure below.[1] Though we have only 67 observations, it is clear that Catholic clergy prefer unification by an overwhelming majority, while Protestant and other clergy prefer to remain in the UK. Regressing preferences for Northern Ireland’s future on clergy religious identification, and using the other, smaller traditions as the reference category, the relationships do not achieve significance. When controlling for general attitudes toward unification with Europe[2], however, interesting results emerge. Presbyterians are indistinguishable from the smaller denominations, while Catholic and COI (Church of Ireland) clergy are both strongly supportive of Irish unification. Indeed, their probability of supporting unification is more than twice that of their peers. The probability of Catholic clergy supporting unification is .58, as compared to .23 for their peers; the probability of COI clergy supporting unification is .70, as compared to .31 for their peers.

Regressing preferences for Northern Ireland’s future on clergy religious identification, and using the other, smaller traditions as the reference category, the relationships do not achieve significance. When controlling for general attitudes toward unification with Europe[2], however, interesting results emerge. Presbyterians are indistinguishable from the smaller denominations, while Catholic and COI (Church of Ireland) clergy are both strongly supportive of Irish unification. Indeed, their probability of supporting unification is more than twice that of their peers. The probability of Catholic clergy supporting unification is .58, as compared to .23 for their peers; the probability of COI clergy supporting unification is .70, as compared to .31 for their peers.

Two findings merit further comment. First, the COI finding is surprising at first glance. A member of the Anglican Communion, the COI was effectively the establishment church in Ireland for over 300 years. Catholic churches were confiscated by the state on its behalf, and it was aided by the Penal Laws, which oppressed Catholics and Protestant dissenters who would not assent to membership. Surely these Anglicans would feel a close connection to Britain. The Church of Ireland, however, has always been an all-island church and claims a succession of bishops back to St. Patrick, whereas Presbyterianism has deep ties to Ulster specifically. Scottish Presbyterians were settled in Ulster by the British in the 17th century to establish a Protestant outpost. In the aggregate, then, COI clergy have weaker ties to British unionism than their Protestant peers. Our data indicate that a higher proportion of COI than Presbyterian clergy identify as Irish—as opposed to UK—nationals (46% and 19%, respectively), and COI clergy are less likely than Presbyterian clergy to support unionist political parties such as DUP. Second, as the figure above demonstrates, clergy preferences over Northern Ireland’s constitutional status are strongly linked with attitudes toward Northern Ireland’s place in Europe. As support for European unification goes up, so too does the probability of support for Irish unification. The default view looking at politics in Northern Ireland is to reduce political conflict to community conflict, and of course that is present, but there is also a clear globalist subtext. Supporters of Irish unification prefer deeper connections to Europe, not simply (or even necessarily) a unified Ireland for its own sake. This may be more about a widely diffuse preference for soft borders and cross-border cooperation, which is part and parcel of European unification, than anything else.

Second, as the figure above demonstrates, clergy preferences over Northern Ireland’s constitutional status are strongly linked with attitudes toward Northern Ireland’s place in Europe. As support for European unification goes up, so too does the probability of support for Irish unification. The default view looking at politics in Northern Ireland is to reduce political conflict to community conflict, and of course that is present, but there is also a clear globalist subtext. Supporters of Irish unification prefer deeper connections to Europe, not simply (or even necessarily) a unified Ireland for its own sake. This may be more about a widely diffuse preference for soft borders and cross-border cooperation, which is part and parcel of European unification, than anything else.

If the Brexit vote in Northern Ireland was about Europeanization, then the people of Northern Ireland—Protestants and Catholics alike—are drawn into closer alignment with the Republic. This does not mean that a change in Northern Ireland’s constitutional status is in the offing. But it does mean that Northern Ireland’s political context has changed with the development of a new, cross-cutting alignment. As the people of Northern Ireland grapple with Brexit’s aftereffects, the politics are unsettled. This creates space for clergy to enter a political breach less steeped in ethno-religious nationalism.

Elizabeth A. Oldmixon is associate professor of political science at the University of North Texas and editor-in-chief of Politics and Religion. She can be contacted via Twitter. Further information, including the data used in this analysis, can be found on her personal website.

Notes

[1] Question wording: “In terms of the long-term future of Northern Ireland, which would you prefer? Northern Ireland should: a) remain in the UK and have a strong Assembly and government in Northern Ireland; b) remain in the UK with a direct and strong link to Britain; c) unify with the Republic of Ireland.” The two remain response options were collapse for ease of analysis.

[2] Question wording: European Unification Scale: 0 = European unification has already gone too far to 10 = European unification should be pushed further

[…] for the long-term future of Northern Ireland. The results are provided in the figure below.[1] Though we have only 67 observations, it is clear that Catholic clergy prefer unification by an […]

LikeLike