By Paul A. Djupe and Ryan P. Burge

By now, everyone has seen it. The photo op that came at the cost of tear gassing (banned in war by the Geneva Convention) and shooting protesters outside the White House, so Trump could hold up a bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church, while a DC Bishop expressed outrage at the stunt:

Elizabeth Warren, also, expressed outrage, but perhaps got it wrong by calling it a “useless photo-op.” Holding the bible in the air against the backdrop of a protest-damaged church after giving a ‘law and order’ speech continues a long, powerful thread in Trump’s presidency: White Christians are under threat by forces arrayed against their values, their institutions, even their persons.

How do we know? Because we asked and they told us.

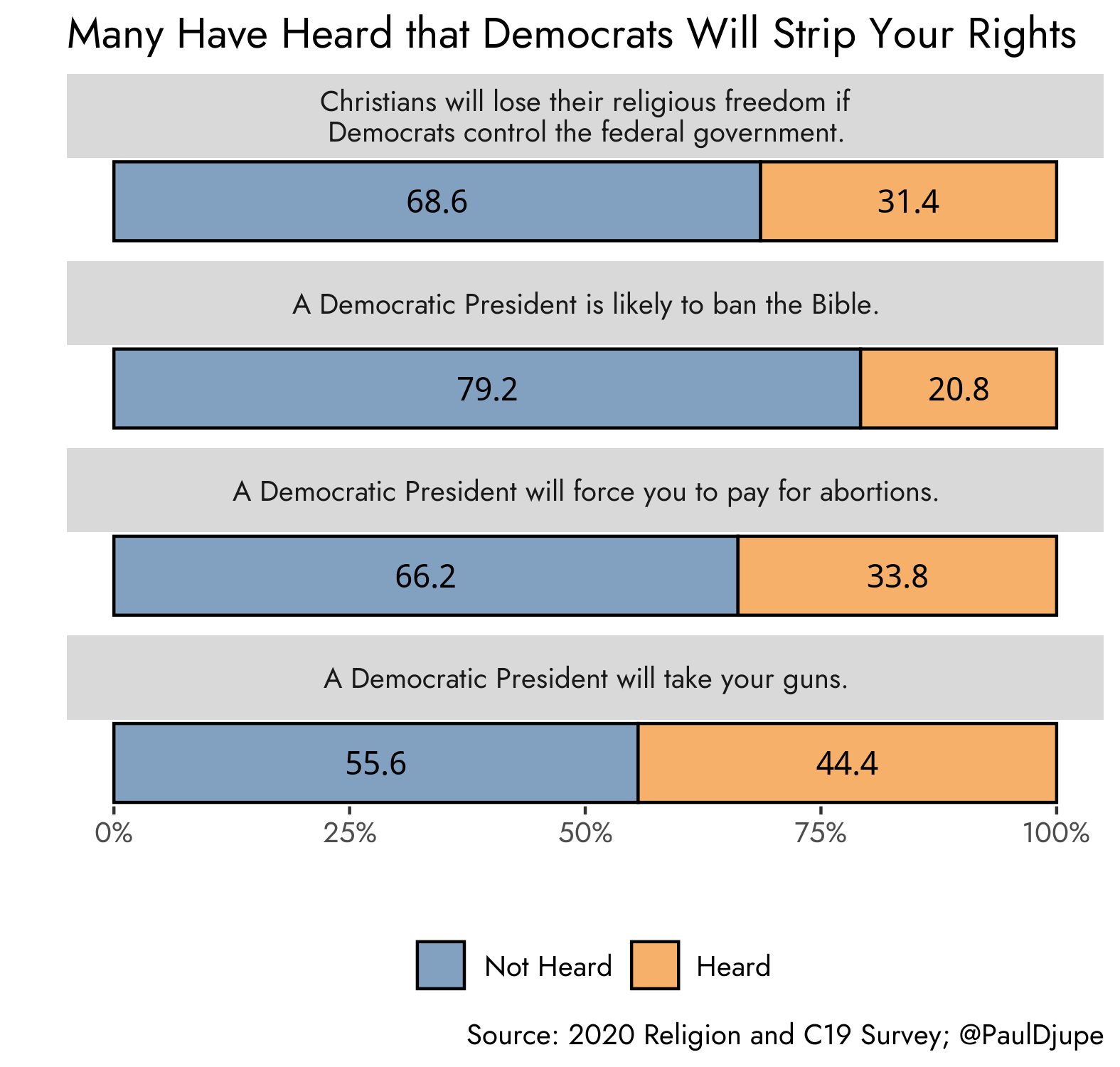

In late March, we surveyed a non-probability sample of 3,100 Americans using quotas to resemble the American adult population along the lines of gender, age, region, and race. We asked whether they believed several threats posed by Democrats and whether they have heard anyone making these claims “in the past few months.” The figure below shows responses to the first question showing that belief in these threats exists, even if it is not widespread. They range from reasonably grounded in some sense of fact (regarding guns – a third believe) to the far-fetched conspiracy theory that a “Democratic president is likely to ban the Bible,” which 20 percent believe.

Somewhat more Americans have heard someone making these claims than believe them as the following figure shows. The proportion hearing that a Democrat would ban (20.8%) the Bible is just shy of the proportion who believe it (22.2%).

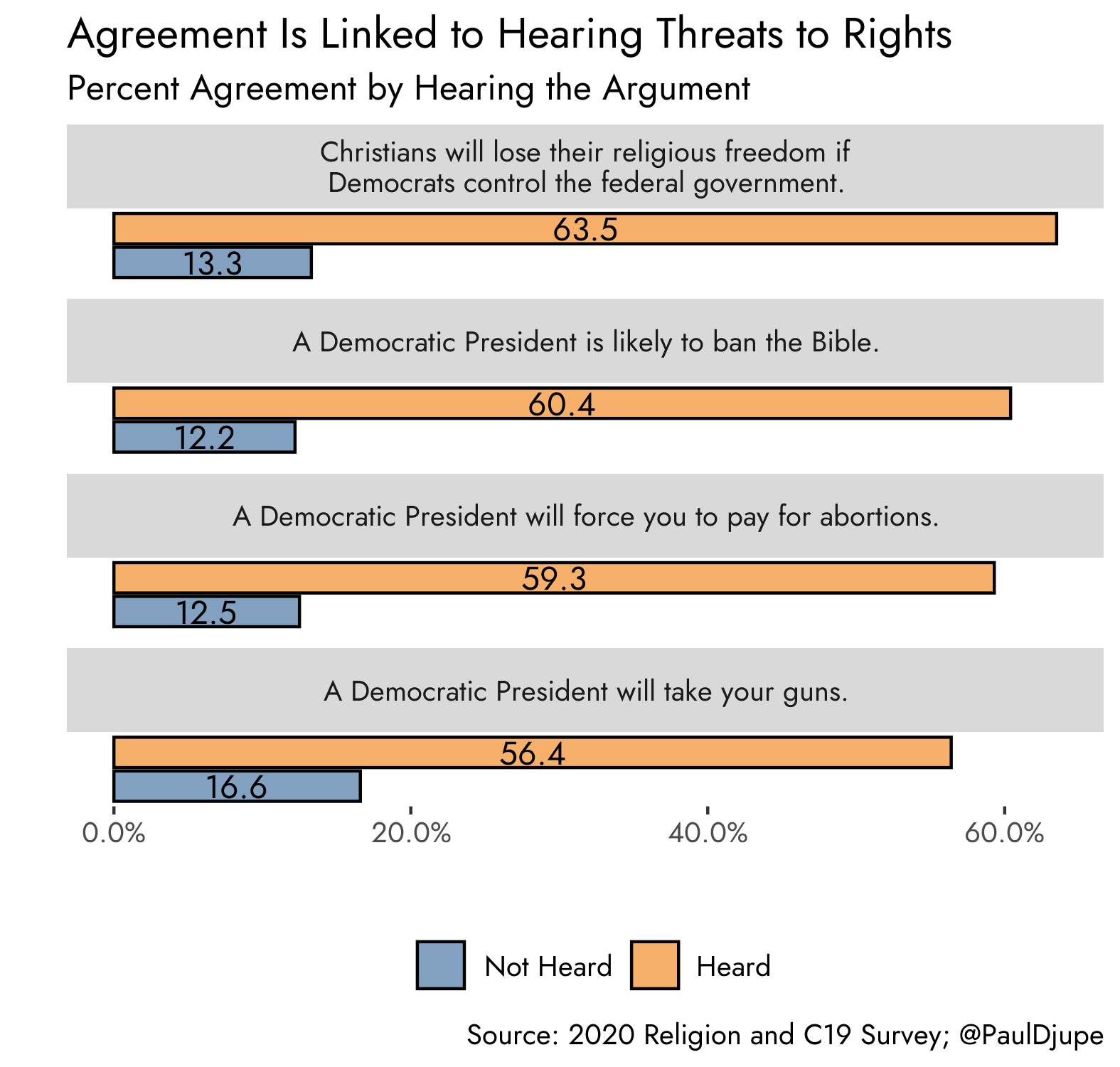

Hearing the argument is no guarantee that you will believe it, but it sure doesn’t hurt. Roughly three-fifths of those who say they heard someone making the argument also believe it. Sixty percent of those who heard that a Democrat would ban the Bible think that the claim has veracity. Of course, this is not causal evidence – conservatives may have selected themselves into contexts where these beliefs float freely. Though in a statistical model that controls for partisanship, worship attendance, religious tradition, and a number of demographic variables, hearing these arguments is still strongly linked to believing these threats from Democrats (at about the same strength as partisanship).

All of this was designed to help inform the dynamics of a question we’ve written about before in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog: “Would Democrats in Congress respect your right to hold rallies, teach, speak freely, and run for public office?” This is not just policy opposition, this is about fundamental citizenship rights. We found that white evangelicals were quite likely to say no and the measures reported above would help us understand its dimensions, particularly if this belief was mobilized.

Below, we modeled the sample’s probability of saying ‘no,’ that Democrats would not respect their rights, given how many Democratic threat arguments they have heard (the model included a number of other relevant variables). Below we can see that only to a minor extent does the effect of hearing these arguments hinge on partisanship. Among Republicans, the probability of saying ‘no’ jumps from 49 percent when hearing none of these arguments to 71 percent when hearing all four. Among independents, the same jump is 34 (hearing 0) to 53 percent (hearing all 4). Only among Democrats does the effect shrink down from ~20 points to 11 (14 to 25). Our best estimate is that hearing people make these arguments about the threat Democrats pose is effective in mobilizing threat and is not simply a function of partisan sorting.

For as ham-handed as Trump’s use of religion is, he knows who buys what he’s selling. Tapping into religious conservative contexts has netted tremendous payoff – an unwavering, morally flexible source of support. The advantage of these measures is that we do not have to rely on pre-existing groups and make assumptions about what they’re talking about. Instead, we can assess directly what influence hearing these arguments appear to have on support for Trump. That’s shown below using a model of a feeling thermometer (running from 0/cold – 100/warm) that controls for other explanations.

Republicans, of course, already run warm in their feelings toward their president, but those hearing more about Democratic threats to their liberties express even warmer feelings. Republicans gain 11 points (67-78), Independents gain over 20 (29-51), and even Democrats gain a substantial degree of warmth (13 points, from 19-32).

Unfortunately, this is not the first time that the bible has been used as a political prop. In the election of 1800, John Adams campaigned on the fact that Thomas Jefferson was antagonistic to religion. Adams’ messaging was so effective that when Jefferson was announced as the next President, families in New England began to bury their bibles in the ground or hid them in wells so that Jefferson’s regime would not confiscate them.

The very stable genius of Donald Trump is signaling to his followers that their worst fears are founded. This is why he makes no attempt to unify and pacify the nation – it would send the opposite signal that we share common values, that we share a basic humanity. Some say they find such messages in the Bible. Used as Trump did last night, the Bible stands for the complete opposite, a symbol of a culture and people under siege. And it’s working.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Ryan P. Burge teaches at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. He can be contacted via Twitter or his personal website.

[…] University) conducted a survey in late March asking thousands of Americans what they thought about perceived “threats posed by Democrats.” Did they believe them? Or did they know […]

LikeLike

I really appreciate the research you guys are doing. It really sheds light on the dynamic that’s shaping political and social life today.

One caveat that could be worth mentioning, though, is the possible self-selection that may account for one’s frequency of exposure to these beliefs. People on the higher end may be there because prior attitudes or social relationships have already led them to tune in to media or associate in venues where these claims are prominent.

LikeLike

Thanks, Roger, we agree. The funny thing that suggests at least some influence is that this cuts across partisan lines to an extent.

LikeLike

In a country where seven states have it in their state constitutions to not allow non-believers to hold public office. They need to deal with reality. No one is going to ban the Bible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] of Christians if given control of the federal government. We’ve talked about this measure in an earlier post about how many people think that a Democratic president would ban the Bible. I’m starting to call […]

LikeLike

[…] We’ve shown before that a sizable portion of Americans believe notions like these, in part because these arguments are frequently being made publicly by Christian Right, Republican figures. I would like to take a different tack in this post, looking for evidence that people are drawing lines in the sand, that political stances might limit good standing in the faith. Is political diversity acceptable to Christians? […]

LikeLike

[…] Yes. In a survey that is just wrapping up this week weighted to match the national population [1], we find that among weekly attending whites, over 60% agree that “Donald Trump was anointed by God to become President of the United States.” Agreement steadily deteriorates among non-evangelicals as their worship attendance slides, but it remains high among evangelicals who are more infrequent attenders. There is simply no way to argue that evangelical support for Trump is situated among the less observant among their ranks. Instead, the evidence points to a closed communication system that reinforces Republican tendencies with novel systems of beliefs about the consequences of Republican ceding control. […]

LikeLike

[…] that never materialize — they’ll send jack-booted thugs to confiscate your guns; they’ll outlaw Christianity; they’ll put conservatives in concentration camps; they’ll institute communism; they’ll […]

LikeLike

[…] that of other Americans. And this final figure (below) highlights just how different. Following our previous research, we included items asking if survey participants had heard anyone making the claims that Christians […]

LikeLike

[…] evangelicals frequently indulge in even darker fantasies, imagining their religious practice could actually be banned and that they could be arrested or even executed for practicing their faith by, for example, […]

LikeLike

[…] politics is a hardball game not for the weak of spirit. Because the stakes are perceived to be so high, it pays to have a motivating force to match. That is, politics is about winning, it’s about […]

LikeLike

[…] of life are threatened, so much so that many believed that the incoming Biden administration would ban the Bible. Such sentiments encouraged a growing religious significance to the presidency and to Donald Trump […]

LikeLike