By Paul A. Djupe

It’s election season and conservative elites are continuing the steady drumbeat of demonization. Franklin Graham, son of Billy, took away from the nominating conventions that Democrats are “opposed to faith.” Others riffed on this line, suggesting that it is a sin to vote for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris or even that it is a “serious sin” akin to murder. Pastor John MacArthur, held in contempt for violating California covid gathering orders, argued that “any real, true believer” will be forced to vote for Trump. According to one commentator, it is “better to cut off your hand than use it to vote for Biden.” Graham blew up these concerns to apocalyptic proportions: “I believe the storm is coming. You’re going to see Christians attacked; you’re going to see churches close; you’re going to see a real hatred expressed toward people of faith. That’s coming.”

We’ve shown before that a sizable portion of Americans believe notions like these, in part because these arguments are frequently being made publicly by Christian Right, Republican figures. I would like to take a different tack in this post, looking for evidence that people are drawing lines in the sand, that political stances might limit good standing in the faith. Is political diversity acceptable to Christians?

I’m reporting figures from a survey of Protestants that Ryan Burge and I ran in the Fall of 2019. In it, we asked a battery of questions about whether someone could be considered a “good Christian” if they held certain attitudes. Shown in the figure below is how partisans responded to each attribute: being pro-choice, a Democrat, a Republican, being pro-death penality, and being for same-sex marriage. I collapsed ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ responses to form the percentages in the figure.

It is perhaps no surprise that Democrats (and these are largely white Protestant Democrats given the sample), are the most inclusive in their definition of a good Christian. In no case does a majority exclude a person because of their political stance, even for Republicans. It is no surprise that Republicans are far less inclusive. Over 75 percent say being pro-choice and pro-same-sex marriage disqualifies someone from being in good standing with their faith. They are also far less willing than Democrats (54 vs 76 percent) to label members of the opposite party “good Christians.” There is only one instance where Democratic Protestants are less inclusive and that’s for supporting the death penalty. It’s also worth remarking that independents are the least inclusive of all, on average, though this is a function of them frequently choosing the middle option (“neither agree nor disagree”).

It is easy to chalk up these sentiments to political attachments – Republicans have been polarizing at a more rapid clip than Democrats and Republican elites are shopping much harsher rhetoric about Democrats, that they will lay waste to America if elected. So, are these patterns merely a representation of partisan identification or does religion have an independent role to play?

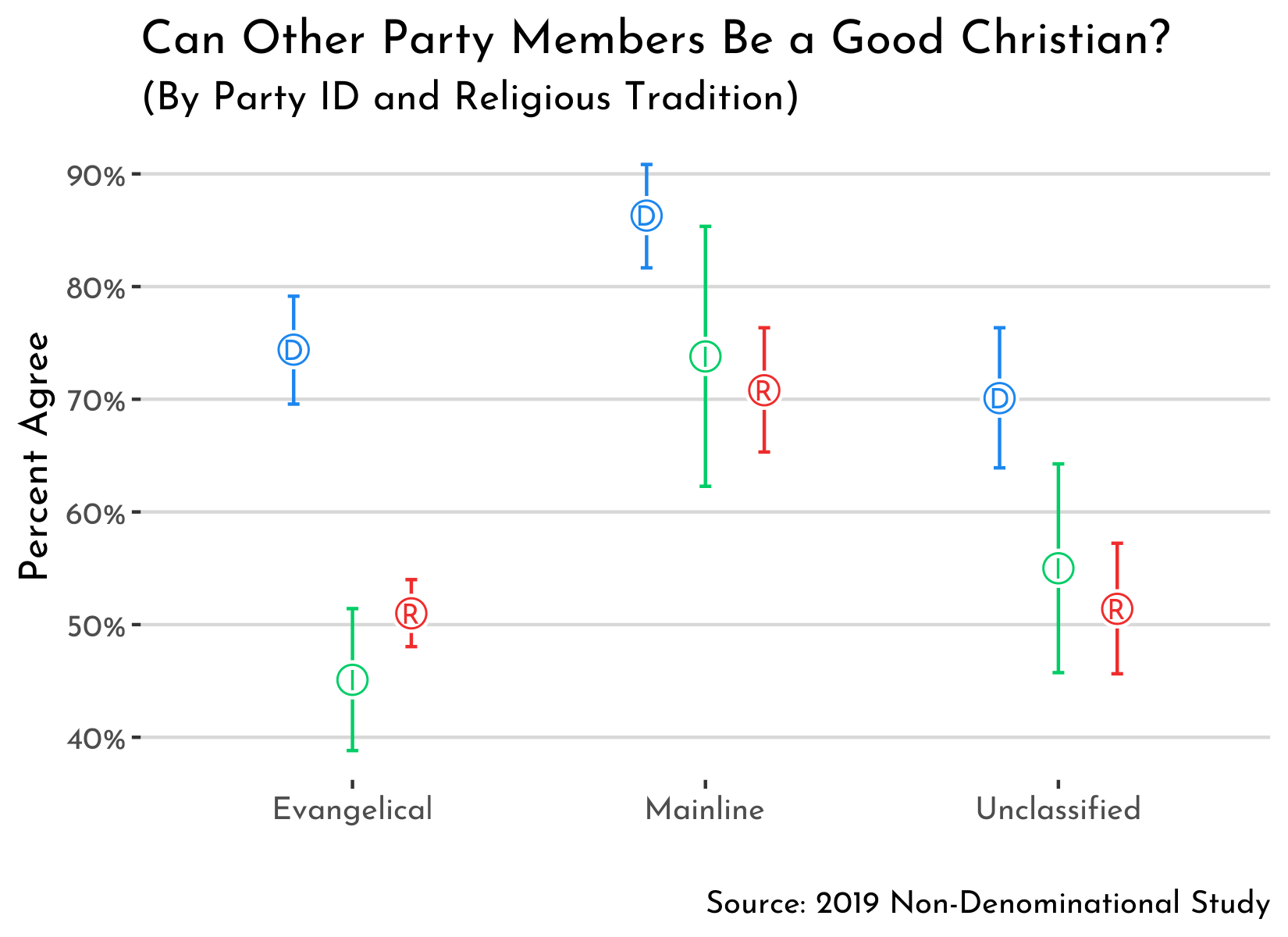

One way to tell is to examine whether partisans in different religious families are more or less inclusive. The figure below differentiates our Protestant sample into evangelicals, mainline Protestants, and the unclassified and then by their partisan identification. It is clear that evangelical partisans are quite different from their mainline counterparts. For instance, 75 percent of evangelical Democrats believe that a Republican can be a good Christian, compared to 86 percent of mainline Democrats. But only 51 percent of evangelical Republicans believe a Democrat can be a good Christian compared to 71 percent of mainline Republicans. Why?

One reason, noted above, is that Republican elites are simply making much more strident claims and evangelical Republicans are more exposed to them. Mainliners are more politically diverse, which means a less concentrated message stream of division, despair, and chaos is aimed at them. Another reason is that mainliners are less likely to have worldview components that make them receptive to the demonization of the other side. One prominent example is Christian nationalism. I measured this with 6 items taken from a Baylor University religion survey that have become a standard measurement of the worldview.[1] Does Christian nationalism (CN) help make people less receptive to including the other side?

Yes. But it is particularly interesting that CN works differently for different partisans. For Republicans, greater adherence to CN drives them in the expected direction: toward exclusion of Democrats from the fold. For Democrats, however, CN makes them more inclusive of Republicans. They (CN Democrats) also like Republicans more – much more than CN Republicans like Democrats (there’s a 20 point gap in feeling thermometer scores – not shown).

One could argue that Christian nationalism is simply the Republican Party line at this point, so CN is perhaps not the best indicator of religious influence. So, how about something that is more purely religious? Brian Calfano and I have been asking about inclusive and exclusive values for almost a decade now and I’ve talked about them before on RIP. Inclusive values entail a drive to bring in new people even if the group changes as a result, while exclusive values prioritize maintaining high group boundaries and resistance to change. I expect that the most exclusive subscribers would be the most likely to see the other side as sinful. And that’s exactly what the model results suggest, shown in the figure below. The least inclusive and most exclusive are far less likely to think an outparty member could be a good Christian. Throughout the range of exclusive values, the probability drops 40 percent. The model includes controls for Christian nationalism, religious tradition, partisanship, gender, race, education, and age.

With a political party devoted to demonizing the other side and the democratic process, it is no surprise to see it reflected in the populace. Partisan exclusion is more common among Republicans, exacerbated by religious worldviews that make them susceptible to adopting those views about outpartisans. That is, we cannot simply blame this on the Republican Party and its mediasphere; a certain kind of exclusive religion has provided fertile ground for these divisive messages to take seed and fester. One lesson from prior work of mine with Brian Calfano is that people are not stuck in these worldviews – they hold both elements of inclusion and exclusion and clergy can help elevate one set of values over the other. Of course, clergy efforts one day a week (max) pale in contrast to the effects of the firehose of exclusion from conservative media and politicians.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Note

1. The Christian nationalism items included in the survey were (likert scaled): The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation; The federal government should advocate Christian values; The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state; The success of the United States is part of God’s plan; The federal government should allow prayer in public schools; The federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public spaces.

Very interesting. What did you find when you ran politically inclusive by age? Anecdotally, I’ve noticed a substantial shift in students at Christian colleges. 15 years ago, students would say they struggled to believe someone who was pro-choice could be a Christian. Now, however, students generally say political views have no connection to faith, even if someone if a Communist, Nazi, etc.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, John. I just rechecked and there is a very mild negative effect of age — older Protestants are slightly less inclusive as you’d expect. However, the relationship is insignificant. There’s simply a lot of variation within age groups. Moreover, as we’ve found in other work, young evangelicals are a pretty conservative lot, especially on abortion. Still, that’s an interesting observation and I continue to suspect that evangelical college students are a pretty distinctive subset of the faithful youth.

LikeLike

Great to know. Thanks for looking into it.

LikeLike

Do we have any comparable data for Catholics or Mormons?

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Brian. We happened to have room on a survey of Protestants, but haven’t repeated them in a general population sample. So, no, we don’t have those data, sorry. Perhaps we will this fall.

LikeLike

[…] week I investigated whether US Protestants were intolerant of political diversity within their ranks and found that such line drawing was common, especially among Republican […]

LikeLike