By Paul A. Djupe, Jason M. Adkins, and Jake Neiheisel

In the late stage pandemic, the crucial question involves vaccination deployment and the public’s willingness to get vaccinated. The federal government and the manufacturers have made available enough of the vaccine and vaccination operations have achieved the efficiency of a military operation in many places across the country. If America’s institutions are doing good work toward reaching the herd immunity levels of ~80 percent of the population, are Americans willing to get their Fauci ouchies?

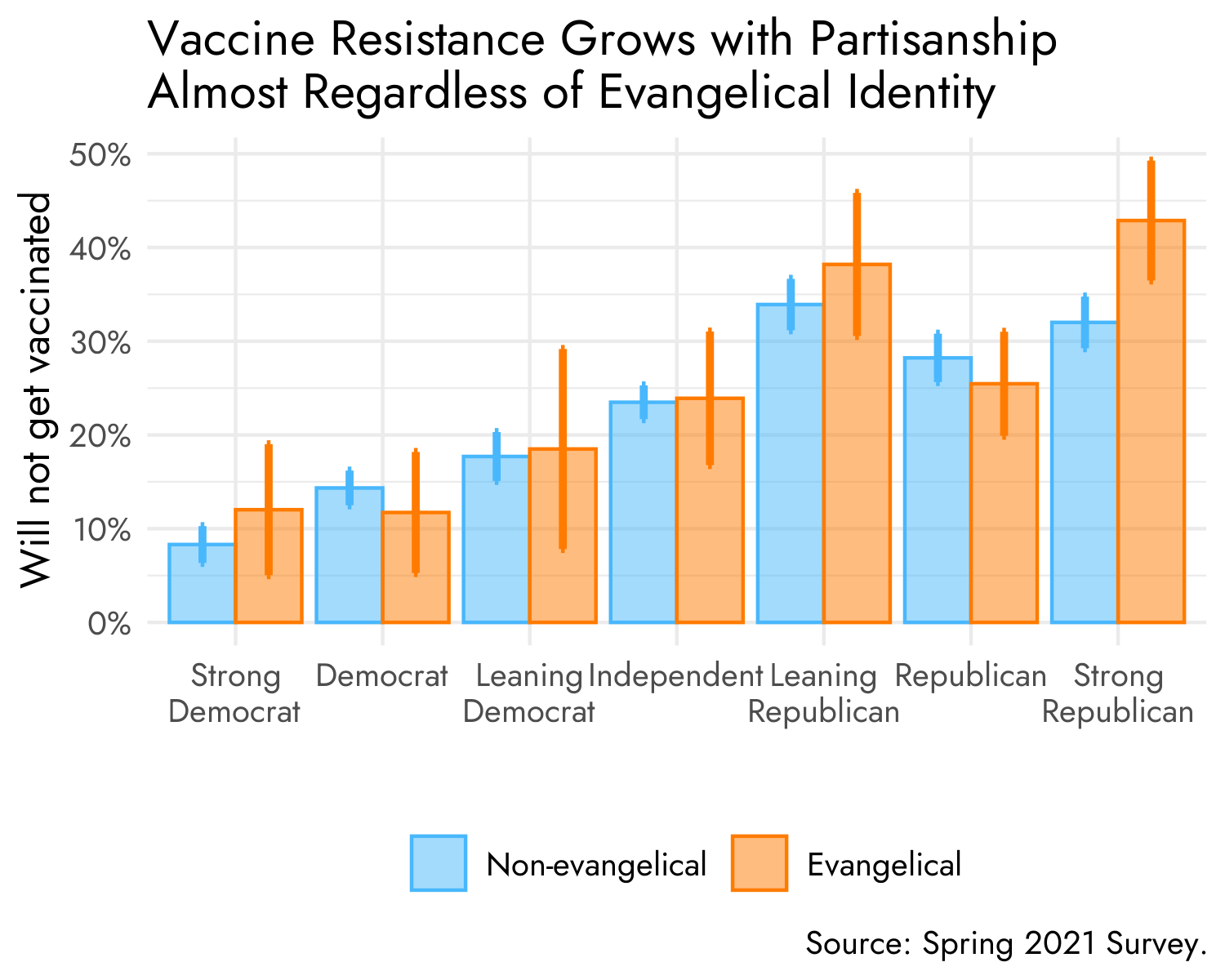

We know well that the answer is mostly ‘yes’ with some significant holdouts. Pew polled regularly about this and found a growing portion of Americans willing to be vaccinated, rising from 51 percent in September 2020 to 69 percent in February 2021. Racial minorities, people with lower income, and Republicans are less likely to indicate vaccine willingness.

But what about religion? As usual, there are good reasons to think that religion is playing both sides, boosting a pro-social willingness to get vaccinated as well as fueling the resistance to this collective effort. For instance, culture warrior Franklin Graham based his pro-vaccine message on the Biblical parable of the Good Samaritan and suggested that Jesus would be in favor of vaccinations, though he is apparently still taking heat for this position. The US Catholic Bishops allowed that vaccines were “morally permissible” as long as there are also “appropriate expressions of protest against the origins of these vaccines,” which apparently are remotely connected to stem cell lines they object to.

At the same time, various far-right groups and figures have been pushing anti-vax information. Right Wing Watch notes Lin Wood arguing that he trusts “God’s promise of protection,” and Marjorie Taylor Greene calling proposed vaccine passports “Biden’s Mark of the Beast.” Conservative Christianity is chock full of QAnon, far-right perspectives these days, so it is highly likely that we will find some here.

We’ve been collecting data through panel-provider Lucid for the last month with a sample size of 3,600. Results provided below have weights applied so that demographics of survey respondents approximate a national audience on gender, race, age, and education.

It’s important to note that partisanship appears to rule the roost. If evangelicals (measured through denominational identity) do not stand out as distinct from partisans, then that’s rare and telling. They do stand out, though, among strong Republicans and represent the strongest concentration of anti-vaccination attitudes with 43 percent of strong Republican evangelicals indicating disagreement with the statement, “I will get vaccinated against the coronavirus as soon as I am eligible to receive it.”

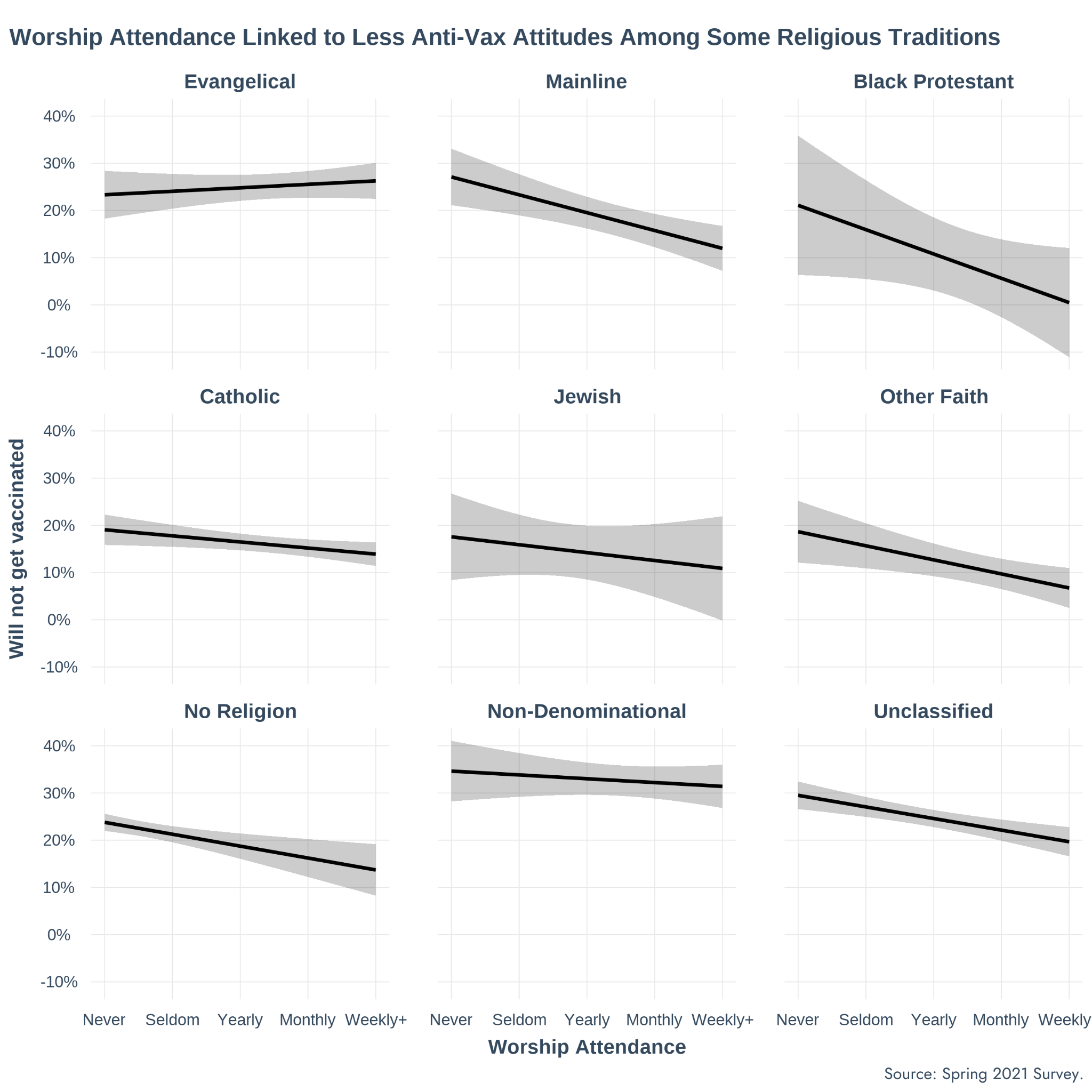

Let’s put aside partisanship for the moment (don’t worry, it will come back) and look at different religious traditions and worship attendance. Though these are heterogeneous categories, it can be helpful to examine data this way to point to further analysis. In this case, the results show that, generally speaking, the more that people attend worship services, the more likely they are vaccine-willing. Take Black Protestants as an example – 20 percent of those who never attend disagree that they’ll get the vaccine when available, but that drops to zero among those who attend weekly (or more often). Most groups show about a 10 percent drop in vaccine unwillingness across the range of attendance. Perhaps one reason why is that frequent attenders are more likely to hear their clergy talk about the pandemic and presumably those messages encourage their cooperation with societal efforts.

However, there are exceptions: evangelical and non-denominational Protestants. For each, their vaccine unwillingness is the highest and it maintains as attendance increases. Evangelicals are in the upper 20s and non-denominationals are in the lower to mid 30s. High attenders among these groups are also likely to hear their clergy talk about the pandemic, but we suspect those messages are not encouraging them to cooperate.

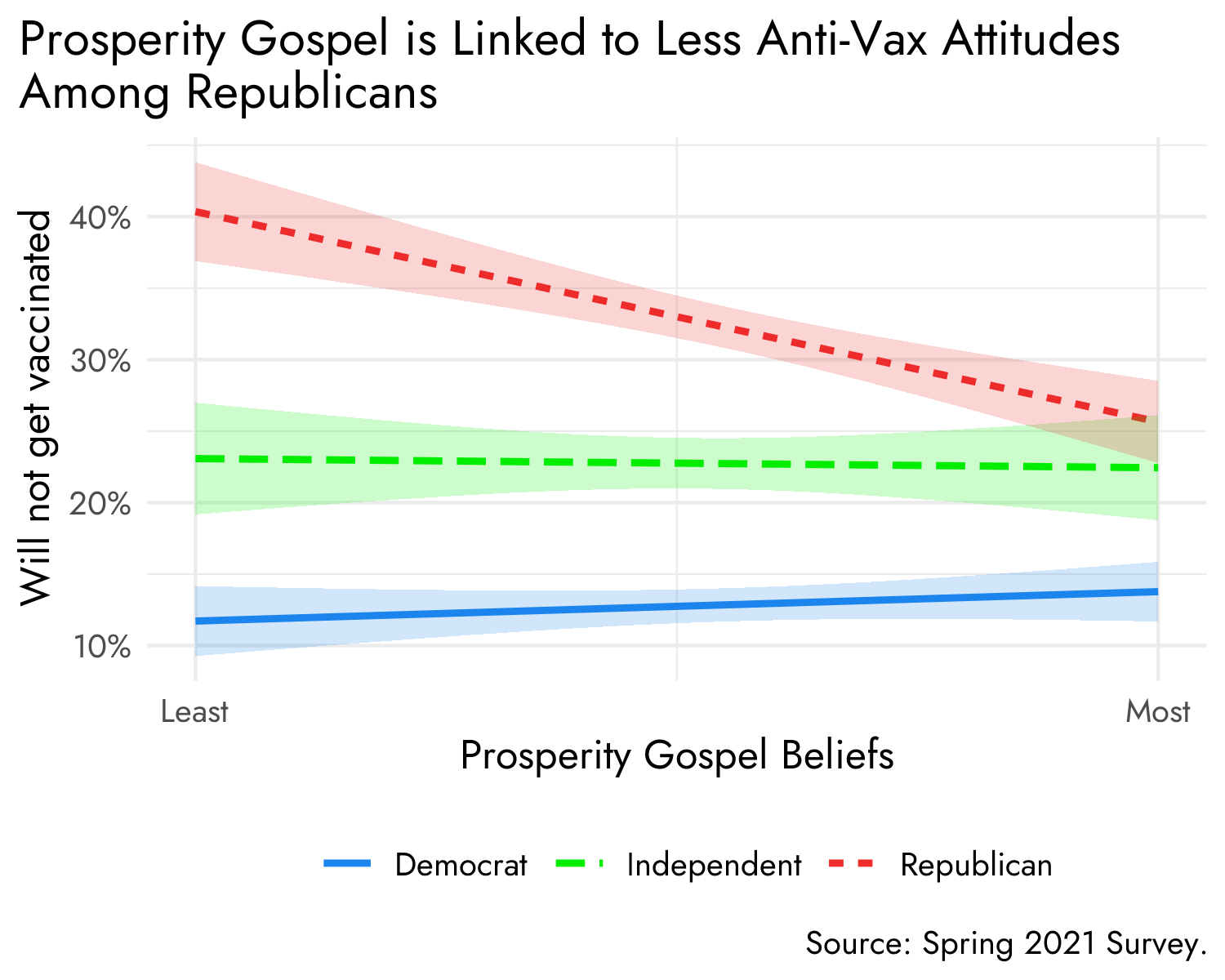

Given the variation across some religious traditions, we suspect that anti-vax attitudes are more common depending on what you believe and what you are exposed to and our survey had a variety of measures to help in this regard. One set of beliefs that featured prominently in the defiance of government orders to close was the prosperity gospel. In their article in Politics & Religion, Djupe and Burge found these beliefs that faith will return material benefits like health and wealth in this life on earth to be quite widespread in American religion and linked to mistrust and defiance. It’s a self-contained system with no need for assistance for the devout, so it would make sense that it is linked to anti-vax efforts as well. The following figure shows, however, that prosperity beliefs have no effect among Democrats and Independents and actually lower the rejection of vaccination efforts among Republicans (the same pattern can be found among whites and nonwhites). Someone has clearly flipped a switch in the prosperity gospel community.

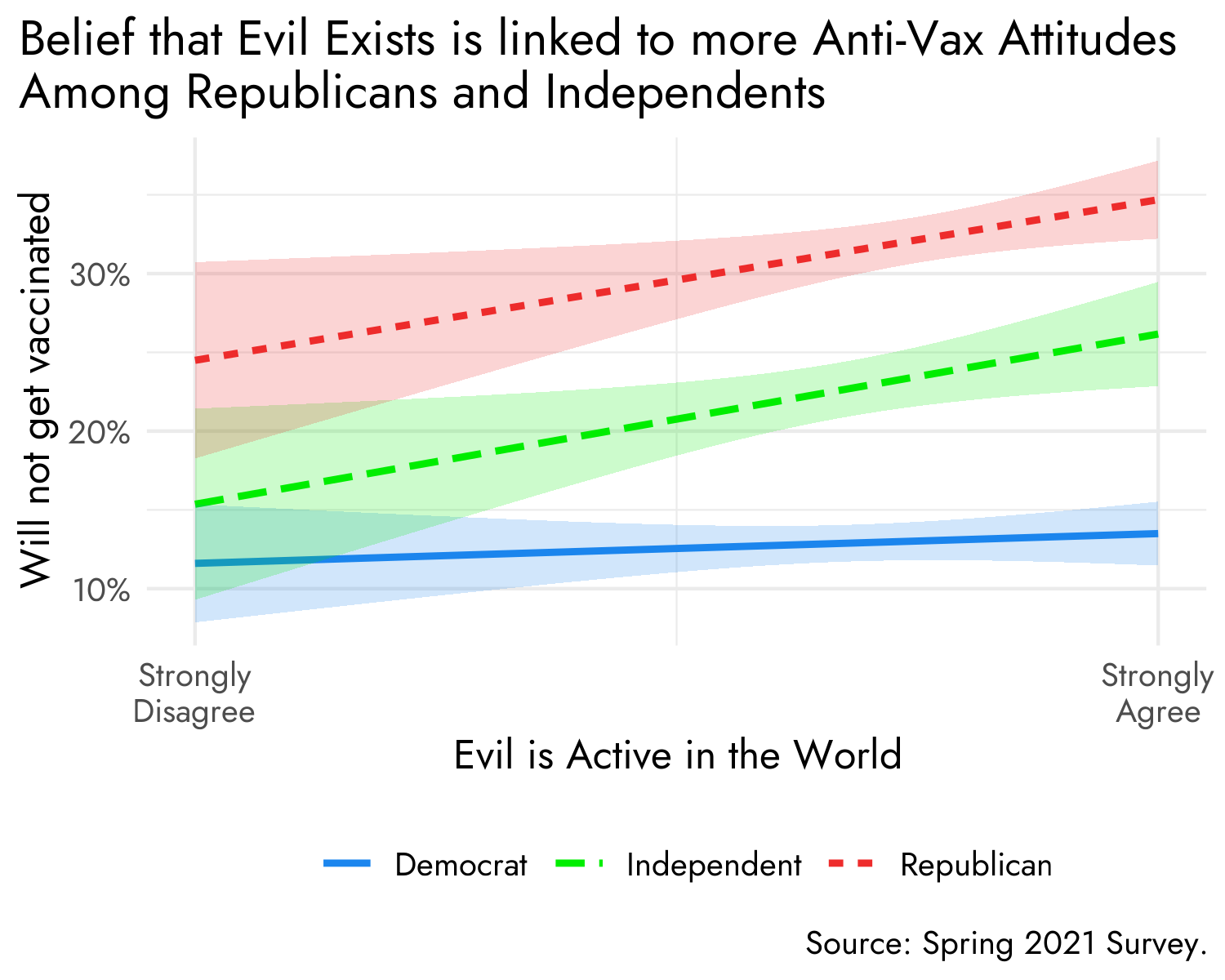

Some believers distrust many large scale, collective efforts outside of the church due to beliefs that evil forces are active in the world. As a result, their radius of trust is short, extending no farther than the family and church members. MT Greene just labeled a vaccine passport as bearing the mark of the devil, so perhaps there is a link between anti-vax and a belief in active evil in the world (we combine agreement with three statements: The devil exists; There is evil out in the world; and We must make every effort to avoid sinful people). The figure below shows that there is a link, but again it is conditional on partisanship. There’s no relationship among Democrats, but belief that there is active evil in the world is linked to greater anti-vax attitudes among Republicans and Independents.

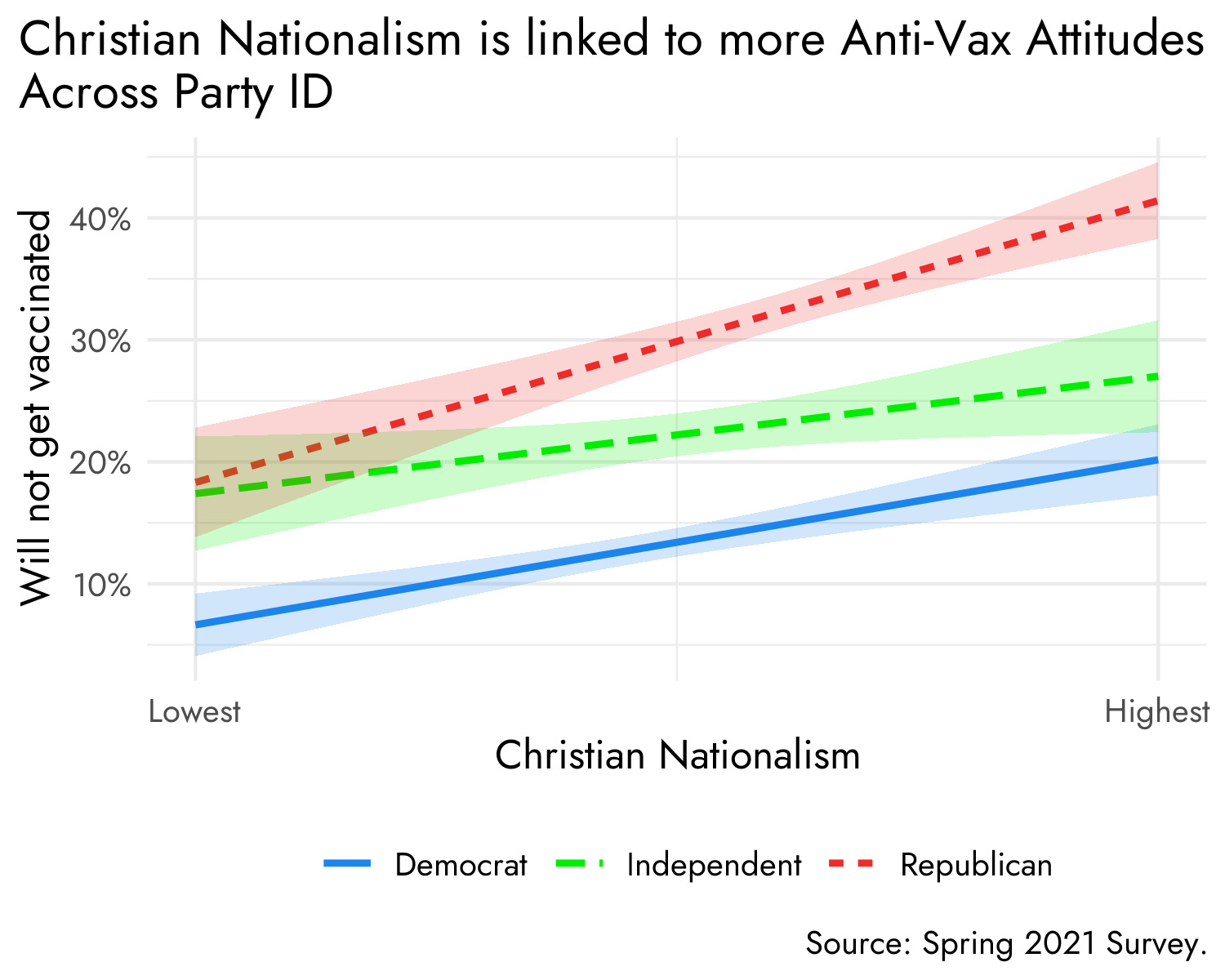

Belief in evil in the world is highly correlated with Christian nationalism, so do they show the same pattern? In some ways, yes. Anti-vax attitudes rise with Christian nationalism, especially among Republicans, but the same basic pattern is in evidence even among Democrats. For each, going from the least to the highest levels of Christian nationalism, opposition to vaccinating doubles (from 10-20% among Democrats and 20-40% among Republicans. The relationship is much weaker among independents, which isn’t surprising since they pay less attention to political communication.

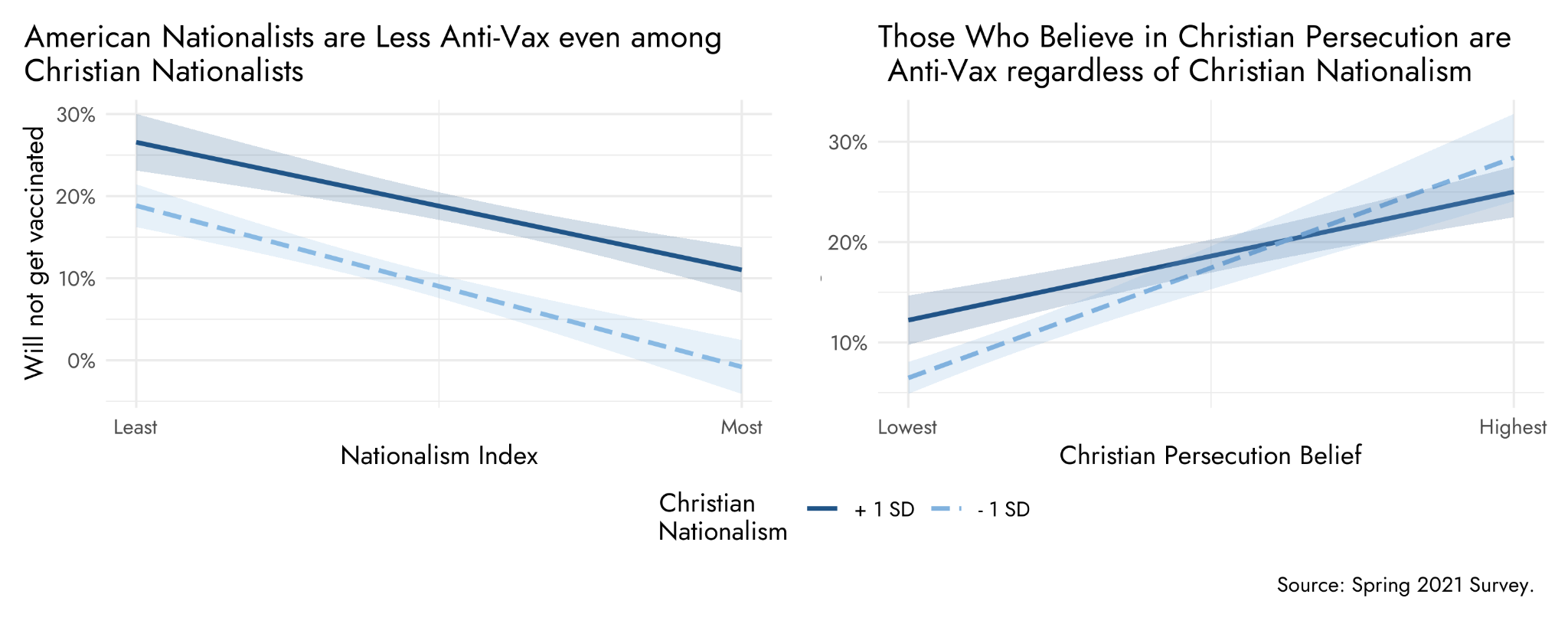

That begs the question about why Christian nationalism is linked to anti-vax attitudes. And here we have an interesting bit of leverage to split the component parts of Christian nationalism apart – are anti-vax attitudes more about Christian grievance or nationalism? The vaccination effort has been billed as a nationalistic enterprise, “a wartime undertaking” according to President Biden. In the figure below, we examine how nationalism attitudes and Christian grievance beliefs work with Christian nationalism to shape anti-vax stances. Nationalism is an index of multiple measures about their pride in being an American and how America functions; Christian grievance is an index capturing their beliefs that Christians would be persecuted under a Democratic administration in various ways.

The results are clear that nationalists are more likely to support being vaccinated, even among Christian nationalists. Those high in Christian nationalism are still more anti-vax, but less so when they have more national pride. So, the positive relationship between CN and anti-vax attitudes is about their anti-nationalism? The figure in the right panel highlights that belief in Christian persecution by Democrats is strongly linked to anti-vax attitudes regardless of Christian nationalism. Put together, the evidence suggests that the CN link to anti-vax attitudes is better understood to be about the ‘C’ rather than the ‘N’ – Christian grievance rather than nationalism.

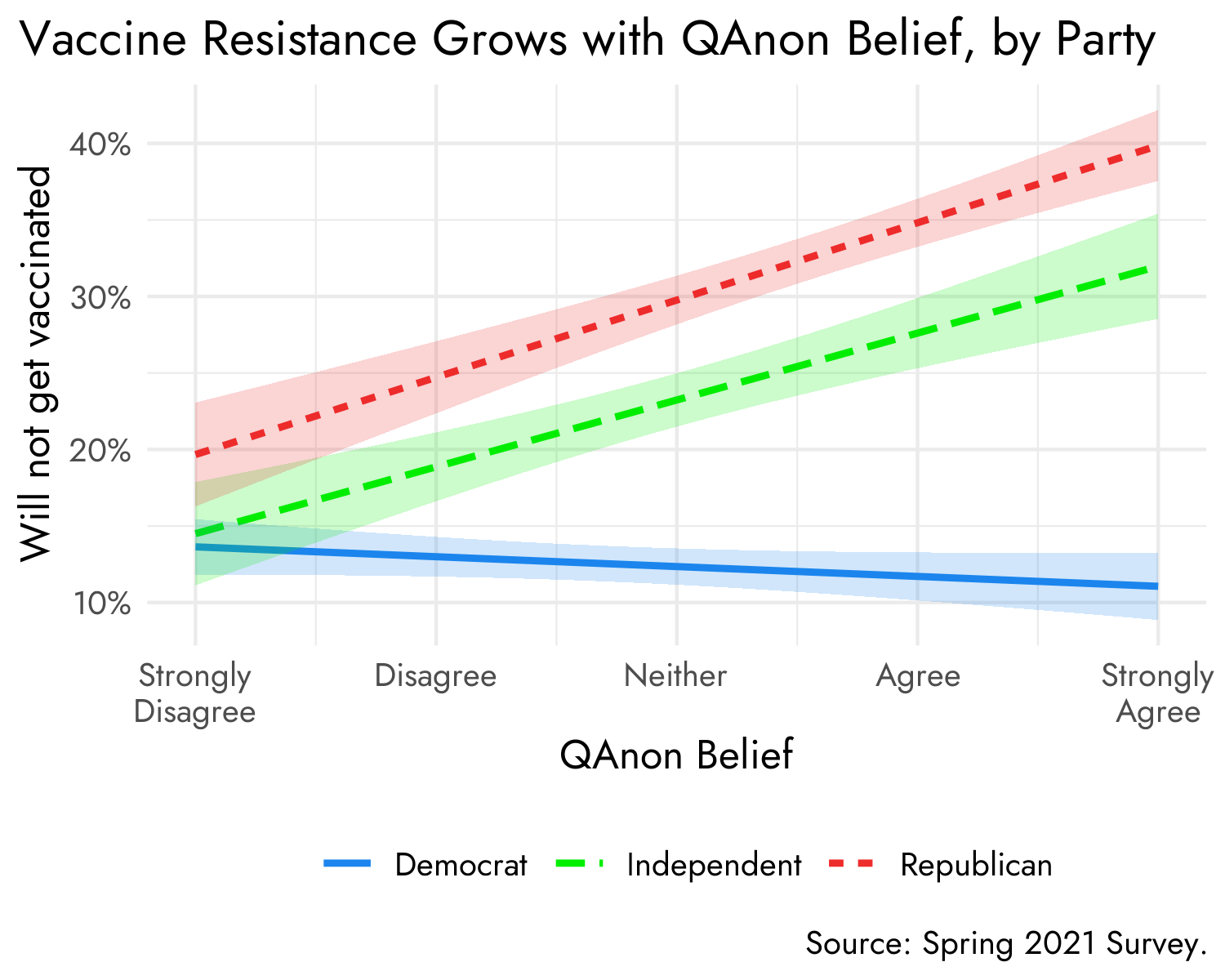

Lastly, we think we all want to know if belief in QAnon is linked to anti-vax attitudes. Anti-vax conspiracies are all over far-right message boards, though less so in social media because of the more or less concerted efforts of the platforms. We used agreement with this statement to capture QAnon belief, “Within the upper reaches of government, media, and finance, a secretive group of elites thwarted Donald Trump’s efforts at reform, fomented street violence, and engaged in child trafficking and other crimes.” It’s no surprise that anti-vax stances climb with greater agreement with this statement, but they hinge on partisanship – Democrats who believe QAnon, and there are some, are not less likely to get vaccinated.

American religion is almost always noted as ambivalent and we add to that characterization here. Religious identities tell us little about why an individual would be cooperative or uncooperative with collective projects, so we turned to a collection of worldviews and beliefs to help us understand the variation among religious people. Vaccine resistance is relatively high – right at the cusp of threatening herd immunity. And much of it is linked to being a Republican. But partisanship doesn’t explain everything and there is considerable variance among Republicans, especially. The more people believe in active evil, forces that will persecute Christians, and that Christians should dominate the United States, the more anti-vax they are, surely in part because Democrats are running the show now. Moreover, we found that Christian nationalist anti-vax stances are more about Christian grievance politics and less about nationalism, which the vaccine effort helps us to pull apart.

The pandemic has been a boon for academic research – there are so many aspects of public life that can be studied because the issues generated by the pandemic and the responses to it are new and different from traditional culture wars issues. For more, look out for the forthcoming book project edited by Paul Djupe and Amanda Friesen: ‘an epidemic on my people’: Religion in the Age of COVID-19 (Temple UP).

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (check out his posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Jason M. Adkins, Montana State University Billings, is an Assistant Professor of Political Science. His research interests include religion and politics, race and ethnic politics, sports and politics, and public administration. He will be joining Morehead State University as an Assistant Professor of Political Science in August 2021.

Jacob R. Neiheisel, University at Buffalo, SUNY, is an Associate Professor of Political Science. His research interests include: religion and politics, political communication, and election administration.

Is it possible to see the No Religion category split out by Atheist/Agnostic/Nothing in Particular?

LikeLike

You bet. Atheists=14.6% (not going to vax), Agnostics=14.1%, and nothing in particulars=25.5%.

LikeLike