By Paul A. Djupe (Denison University) and Ryan P. Burge (Eastern Illinois University)

[This is an extended version of an article posted at the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog]

[Cover image credit: https://observer.com/2017/01/does-art-discriminate-against-christians/%5D

A recent report by Cato Institute researcher Emily Ekins provided a provocative set of findings. Instead of a “basket of deplorables” that has “compromised its Christian values in order to attain political power for Republicans,” Ekins finds that church attending Trump voters actually have a good deal in common with liberals. Using recently collected data from 2016, 2017, and 2018 by the Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group, Ekins finds that among those who voted for Donald Trump, church attendance leads to warm feelings toward minority groups, higher levels of support for international trade and immigration, as well as higher levels of concern for poverty. These data suggest Trump’s drive to undermine American social norms will founder on the ramparts of American piety.

But the critical question that is unexamined in Ekins’ report is this: If church attending Trump voters provide more socially acceptable attitudes, do they translate them into less support for Trump? The logic is simple. When Trump makes disparaging remarks about racial and religious minorities, those with positive feelings toward those groups should register more disapproval toward the President if the social norms are meaningful.

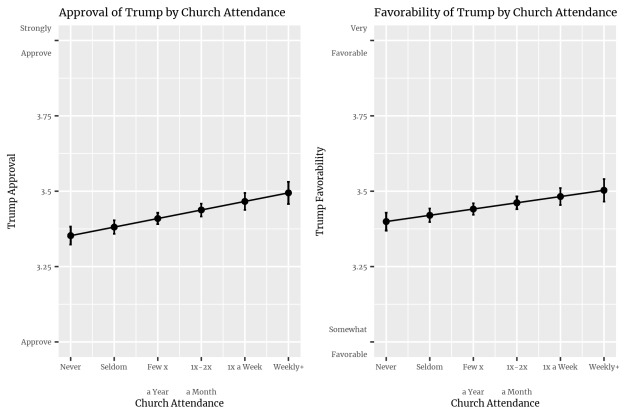

Using the same Voter Study Group dataset, we find this logic does not hold up. In fact, the figure below shows the opposite relationship – more frequent church attendance among 2016 Trump voters is linked to greater favorability and stronger approval ratings of Trump in 2017 (each by about .15 points on a 1-4 scale, which is about 5%).

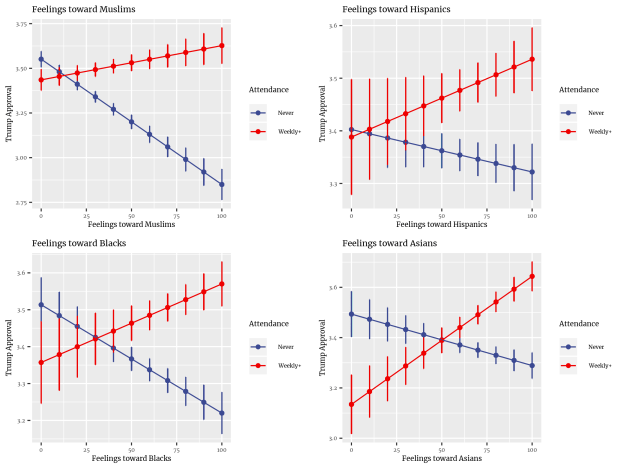

Even when we incorporate the attitudes towards minorities that were featured in Ekins’ report, we find something far short of liberalism. Do Trump voters who hold more positive feelings toward minorities view Trump differently from others? We used 4 different groups asked about in the survey: Blacks, Muslims, Hispanics, and Asians. If these social norms held sway in their political calculus, then we should see a downward slope of each line, which would mean that voters punish Trump for his words and deeds.

Instead, the estimates in the figure below show that frequent church attenders approve of Trump more when they express warmth toward minority groups. Those who never attend church (the blue line) show the expected relationship – those expressing warmth toward minorities penalize the President in their approval ratings. The strength of that effect varies from 20% regarding view of Muslims to about 3% in the case of warmth toward Asians. Of course, this pattern reflects the profound politicization of Muslims.

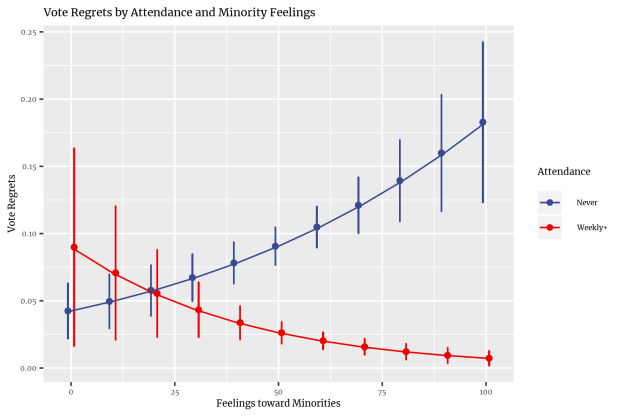

This reversal of expectations is borne out elsewhere in the survey results as well. One of the more telling questions in the survey was one asked early: At this point, do you have any regrets about your vote for president in 2016? Just under 5 percent expressed regrets both overall and among Trump voters. If so many Trump-supporting church attenders have liberal outlooks on politics and toward politically salient groups, they should be more likely to express regrets for their vote for Trump. The figure below shows the opposite. As their warmth toward minorities climbs, the proportion expressing regret drives to zero among frequent church attenders. Only among those who never attend church do we see the expected relationship – warmth toward minorities drives up regret for voting for Trump.

To summarize the argument, Ekins writes, “These data demonstrate how private institutions in civil society may have a positive impact on social conflict and reduce polarization.” This is clearly a positive view of religious institutions, and there is ample published research in the social sciences that finds that churches provide social and political goods to the community. We have both written articles that espouse some of the positive ancillary benefits of church involvement. For example Djupe and colleagues found that churches are good at helping individuals develop civic skills (running a meeting, organizing a fundraising campaign) that are important to political activism, and clergy are likely to press for democratic norms in running their congregations. Burge found that those who attend church at a higher frequency were more likely to express tolerant attitudes toward marginalized members of society. Neither of us are opposed to touting the benefits of religion in our research, but we must be clear: these results do not paint a rosy picture of politics and religion in Trump’s United States.

What is happening here? Why are religious Trump voters showing more support for Trump when they hold more liberal attitudes? We offer two possible reasons. The first reason is that partisanship is their core value and all else is secondary, including their religion. This is the argument from a new book by Michele Margolis and work by a number of others. However, in this case examining only Trump voters, religious individuals link their views with their politics in quite different ways from the non-religious. Something else must be happening.

We suspect that these results may capture socially desirable representations and do not reflect their true attitudes. While it is possible that they are simply dissembling, religious congregations exert considerable pressure on attenders to conform to a set of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Religious voters are likely to be highly tuned to social norms, such as racial inclusion. But we should also acknowledge how staunch Trump support is in many American congregations. Thus, it is quite possible that is socially desirable to be inclusive toward all people all the while expressing full-throated support for Trump. In any case, these results do not support Ekins’ sunny view of the religious right, who contends that there is common ground on which Americans can begin a national conversation anew.

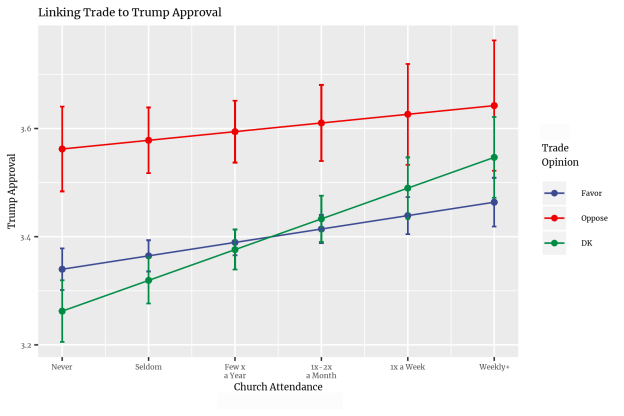

There is no direct evidence to evaluate which of these perspectives has more evidence, but maybe this is suggestive. Ekins also turns to trade policy attitudes to show that religious Trump voters favor increased trade with other nations. We affirm that finding, but that question also has a response category valuable for our purposes: “don’t know” (DK). The DK option has long been understood to both represent those who actually don’t have an opinion, but also as a dodge for those who are sensitive to conflict. If religious Trump voters are feeling pressure to conform, then those religious voters who choose DK should have higher evaluations of Trump. The evidence below is not unequivocal, but is supportive of this interpretation. It shows that while the effect of church attendance is positive among those not opposed to increased trade with other nations, the effect is quite a bit stronger among the DKs than among those in favor (0.3 vs 0.1). There is no church attendance effect among those opposed to more trade, who strongly approve of Trump.

As many have argued from the beginnings of the republic, civil society can act as a brake on government by holding fast to their beliefs and values and using them as a yard stick on government performance. Instead of promoting the use of values to evaluate Trump, churches appear to inhibit their use in quite a radical reversal of how we typically think and talk about the role of churches in society. Of course, this pattern also supports the fears that many observers have expressed, that conservative churches in the US have lost their ability to exercise a prophetic voice to government. It remains to be seen if these relationships hold as time passes from the 2016 election, but the degree to which Trump’s approval ratings have not budged in the last eighteen months suggests his supporters aren’t going anywhere regardless of who they are or what they believe.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University Political Science, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (see his list of posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Ryan P. Burge teaches at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. He can be contacted via Twitter or his personal website.

[…] the past few years have lead us to question a great deal of conventional wisdom. For instance, in a post I wrote with Djupe, we find that the more warmly people who frequently attend church feel toward minorities the more […]

LikeLike

[…] has become clear that we cannot assume the connection between political orientations and support for Trump among evangelicals, so approval […]

LikeLike

[…] and Ryan P. Burge, political scientists at Denison University and Eastern Illinois University, have challenged Ekins. They argue that the seeming racial moderation of white evangelical voters is superficial, far less […]

LikeLike

[…] and Ryan P. Burge, political scientists at Denison University and Eastern Illinois University, have challenged Ekins. They argue that the seeming racial moderation of white evangelical voters is superficial, far less […]

LikeLike

[…] and Ryan P. Burge, political scientists at Denison University and Eastern Illinois University, have challenged Ekins. They argue that the seeming racial moderation of white evangelical voters is superficial, far less […]

LikeLike

[…] and Ryan P. Burge, political scientists at Denison University and Eastern Illinois University, have challenged Ekins. They argue that the seeming racial moderation of white evangelical voters is superficial, far less […]

LikeLike

[…] whites are trending liberal on immigration, that might not affect their votes. As two of us — Djupe and Burge — have shown elsewhere, white evangelicals who hold warmer feelings toward racial and ethnic minorities do not oppose […]

LikeLike