By Paul A. Djupe

A major strategy to keep conservative Christians unified in the 2020 election season is to ramp up perceived and anticipated persecution. As the story goes, Christians are under threat and the only thing that is holding back the persecution dam is Donald Trump and the Republican Party. For instance, Ralph Reed who heads Faith and Freedom Coalition recently claimed that if Trump is denied reelection, “It will be open season” on Christians. In the face of that warning, Reed goes so far as to claim that Christians “deserve” the persecution that is coming if they do not work hard to register Christians and get out the vote.

One reason that Reed’s arguments would seem to have teeth is that he and others have worked hard to convince Christians that many of their ranks are being persecuted now, in the present tense. Finding a considerable amount of perceived discrimination against Christians was the revelation of a 2017 PRRI report, showcasing that Republicans and Democrats inhabit starkly different worlds. Some of the disparities concern race: “fewer than one-third (32 percent) of Republicans believe blacks face a lot of discrimination in society,” compared to “Nearly six in ten (57 percent) Americans [who] say blacks face a lot of discrimination in the U.S. today.” But the disparities concerned religion too – 57 percent of evangelical Protestants claimed there is a lot of discrimination against Christians, which is almost double the sample average. Evangelicals were the only group to perceive more discrimination against Christians than Muslims in America.

I want to push on why people might believe such things. I suspect that they are mobilized from elite communication and are not the result of personal experience. One way of checking that out without communication data is to see if these beliefs cluster geographically. That is, the elite rhetoric above suggests that Democrats and the non-religious are the source of the discrimination, so is perceived discrimination more common in parts of the country that are more secular?

The analysis draws on newly released survey data from the Voter Study Group called Nationscape. We’re used to big datasets like the CCES, but this one is a monster. In 2019, the Nationscape is composed of 155,000 interviews. It’s amazing in some ways, limited in others, but helpful for this analysis. They adopted the PRRI scheme of asking, “How much discrimination is there in the United States today against each of the following groups?” The groups included Christians, Muslims, whites, Blacks, Jews, women, and men. I’m going to focus on responses about Christians for this post.

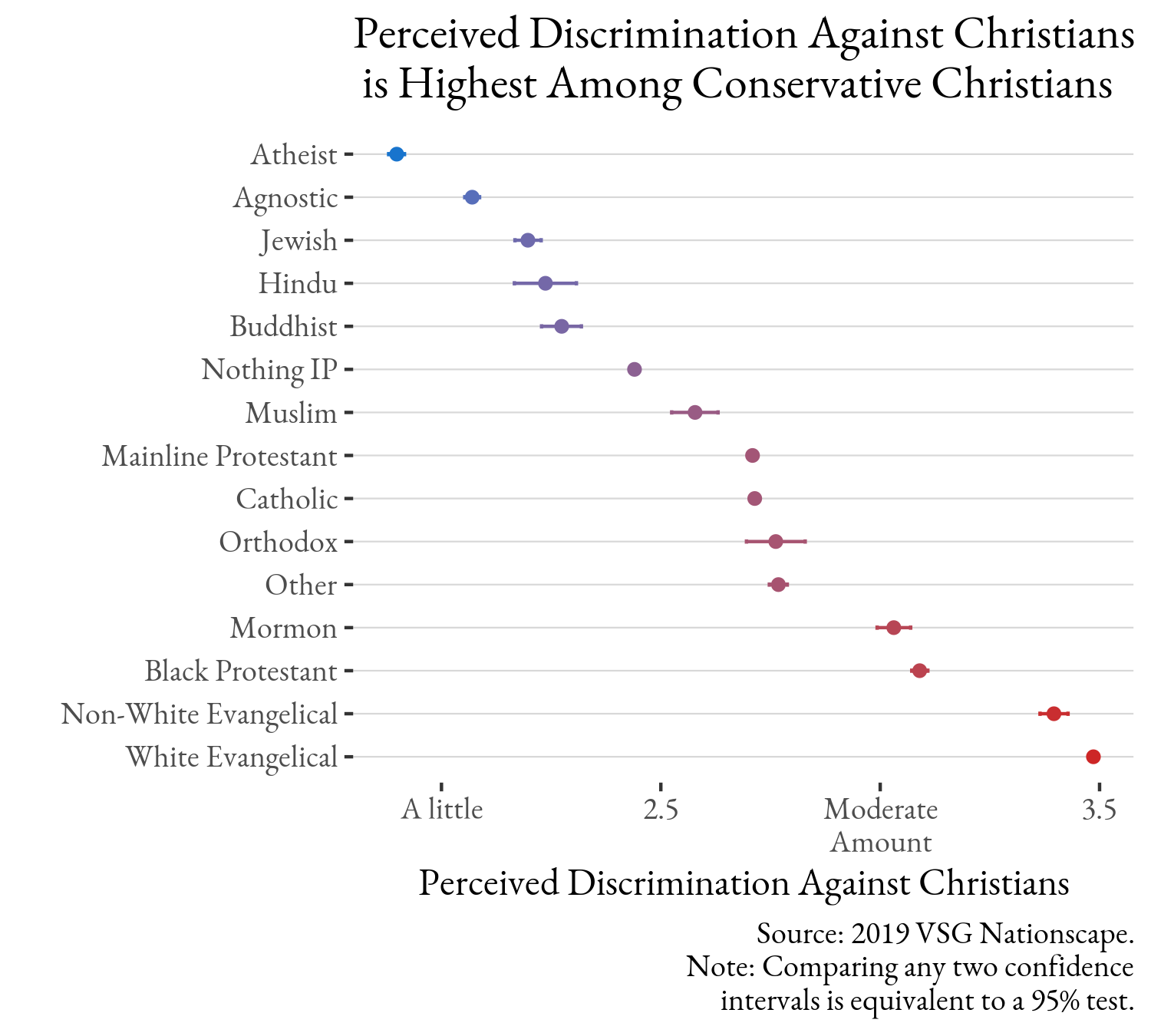

I thought I’d start by examining which religious groups think that Christians are discriminated against. Shown below, it’s no surprise that evangelicals – white or non-white – are the most likely to believe this, while religious minorities and nones are the least. Catholics, mainline Protestants, and Orthodox Christians are in between. It’s not as if groups reject that there is any discrimination – even atheists admit that there probably is “a little” – though evangelicals believe that there is somewhere between “a moderate amount” and “a lot.”

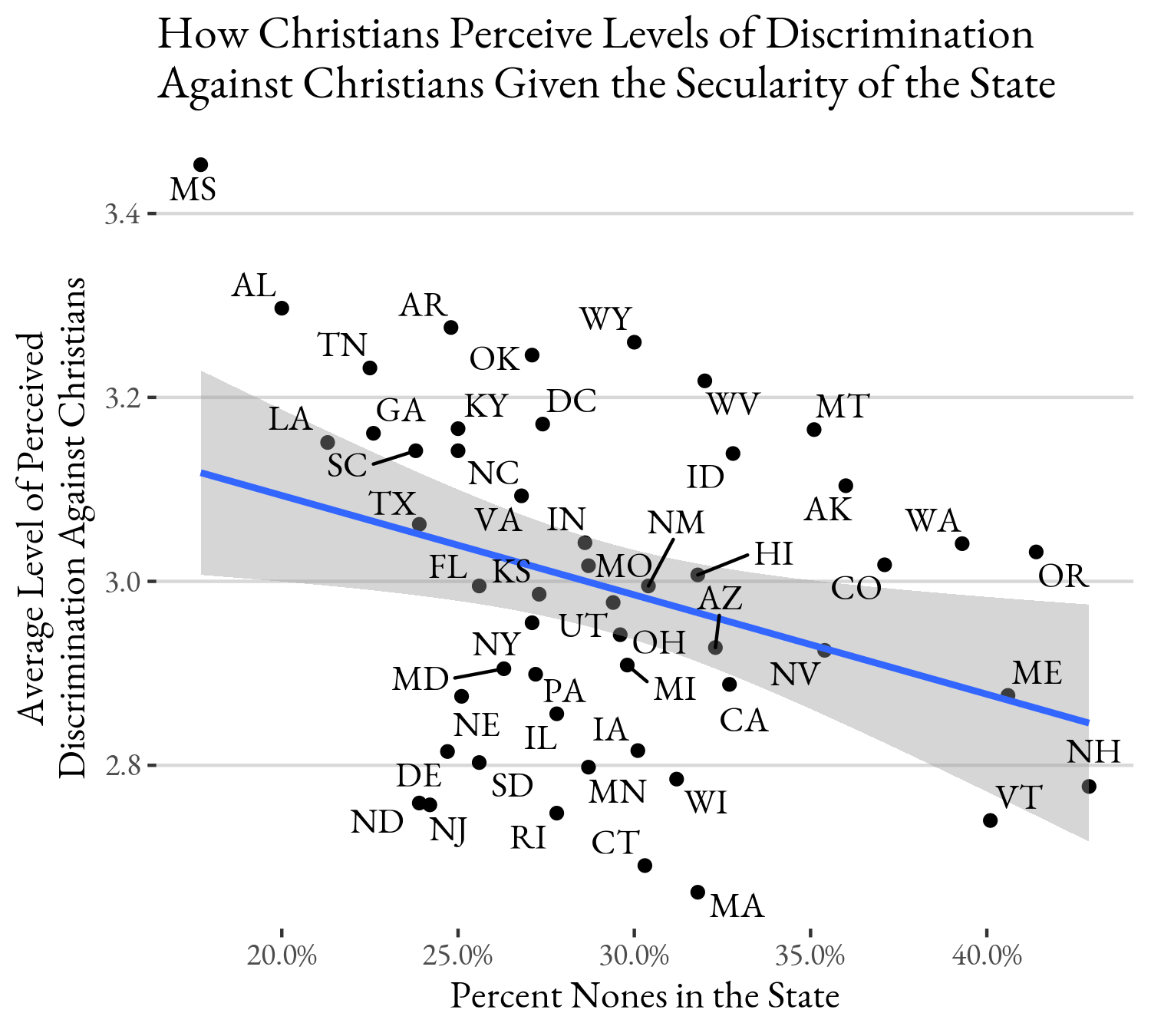

The following figure shows how much Christians within each state believe that Christians face discrimination. If Christians are persecuted by the non-religious, then Christians in Vermont and Oregon would be on top of the list. However, the opposite is true – the highest reported values come from Christians in Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. The lowest rates are reported in the northeast – Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire. This is not the pattern that the elite rhetoric leads us to expect.

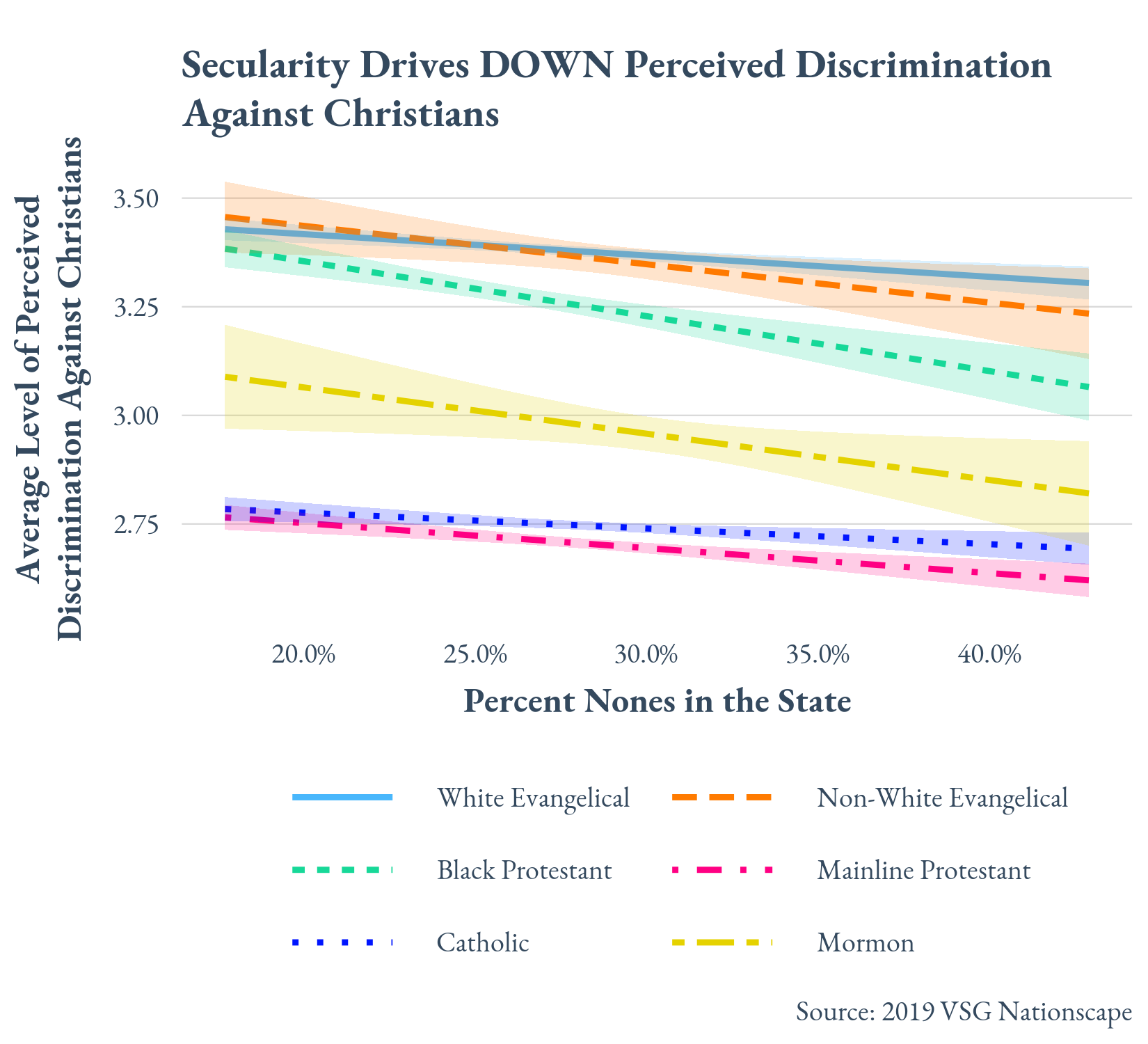

The analysis by state above is not a perfect one. The Christians across those states differ quite a bit – in the Northeast, they are much more likely to be Catholic or Mainline Protestants, and white or black evangelicals in the south. Instead, we need to know how members of each religious group report a belief in discrimination levels based on the secularity of their state. That takes a statistical model (with controls for partisanship, gender, and race). The model allows the effect of state secularity to vary for each religious group (through an ‘interaction term’), so it is perhaps surprising to see how similar the effects are and how they resemble the state-level analysis shown in the prior figure. That is, the secularity of the state drives down beliefs about the level of discrimination against Christians for each Christian religious group. Still, white evangelicals believe at the highest rate, while mainline Protestants believe at the lowest rate, but both rates drop by about the same amount when surrounded by more religious nones.

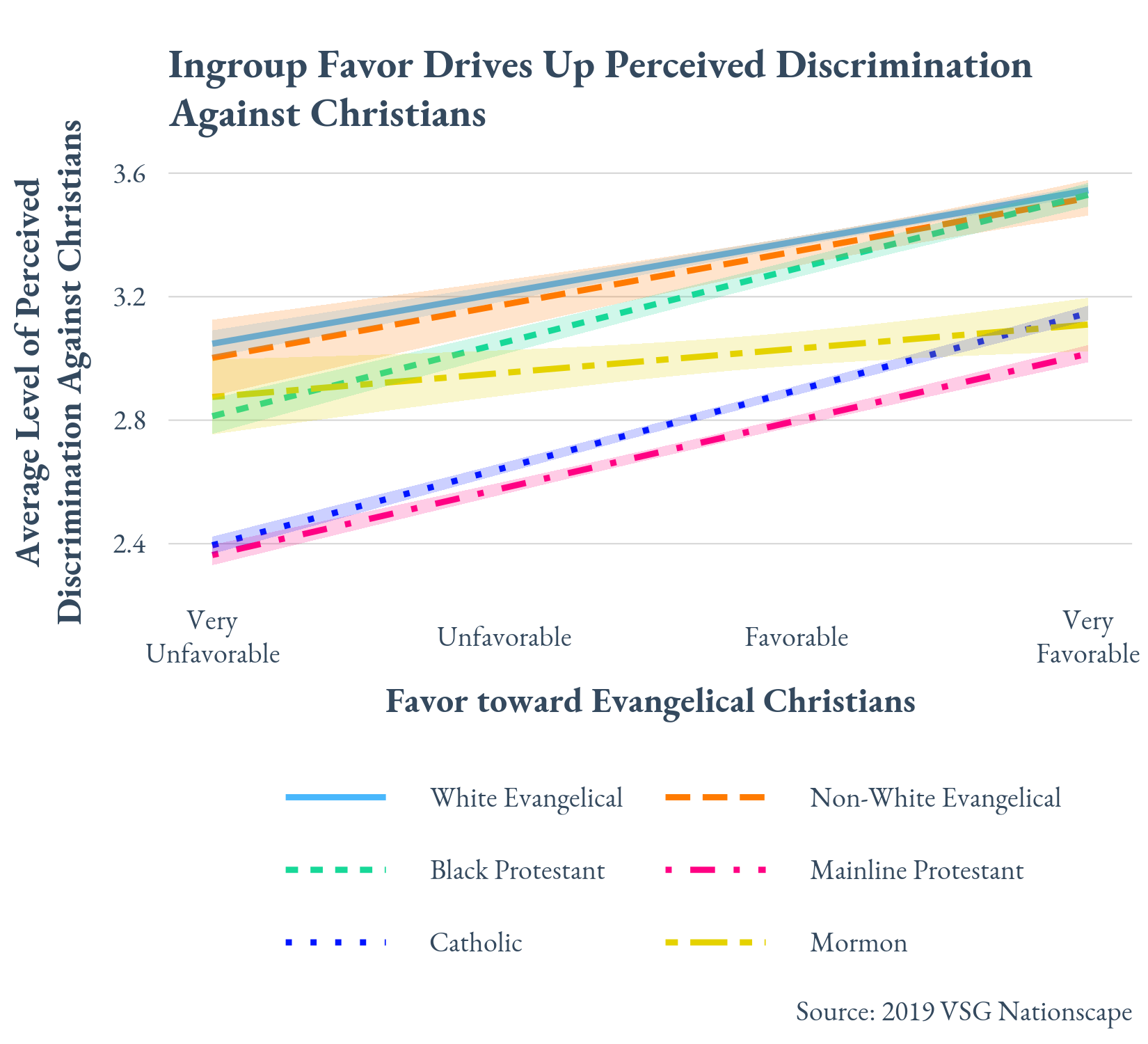

If the effect is really about drawing boundaries around the group, then we would expect that those who feel very favorably toward Christians would espouse the same belief in persecution. The Nationscape survey had such a question for half the sample (so only 70.7k responses), asking how favorably the respondent feels toward “evangelical Christians.” The figure below highlights that the effect works in the same way as being surrounded by less secularity – those feeling more favorable believe there is more persecution against Christians in the US. In all cases, except among LDS identifiers, the most favorable toward evangelicals believe in about 13% more discrimination against Christians in the US.

We well know that we’re living in strange times, with extraordinary claims that are only loosely tethered to facts. But these beliefs create their own facts. By that, I mean that if people believe that they will be persecuted and act accordingly, it helps generate the war they anticipated in their minds. That’s precisely the point of the elites encouraging these beliefs. I’ve already shown that atheists and Democrats are not intolerant as evangelicals believe. The problem is that these beliefs are following the ‘inverted golden rule’ – do unto others as you expect they will do to you. And that has real consequences as the extreme politics of the Christian Right has been driving people out of churches. It also entails a level of extreme politics to maintain their political position as elections (or impeachment trials) take on apocalyptic meaning.

The results in this post suggest that getting out of the social bubble and working with diverse others is one way to counter these beliefs. But we should not discount the value of diverse, pluralistic political environments – more religiously diverse states are also likely to be more supportive of universal religious liberty, not the pinched versions designed to further insulate evangelicals from shifting political winds and enable continued discrimination.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Very interesting supportive data. Not surprising.

LikeLike

[…] people outside of their social worlds. Of course, this is just what might be contributing to their sense of threat felt from others. This pattern also makes sense given the structure of the religious group – it is highly […]

LikeLike

[…] this tale. For one, conservative Christian perceptions of discrimination against Christians are higher in states with stronger Christian majorities. And conservative Christians are willing to strip the rights of groups (e.g., atheists) who they […]

LikeLike

[…] to take back America from the “demonic forces” pushing Trump’s impeachment who would strip Christians of their religious freedom if they regained control of the federal government, makes it clear that extreme measures would not […]

LikeLike