By Paul A. Djupe

Since the beginning of the Trump era in early 2016, observers have been puzzled by evangelical support for Donald Trump. He is not religious in any meaning of the word and then has a long list of personal foibles that have been right there, out in the open for all to see. Nevertheless, evangelicals embraced him, have seen a divine purpose running through him, and even changed their values to reinforce support for him according to PRRI data. In this post, I’m interested in whether religious people know that there appears to be a cost of associating their religion with Trump.

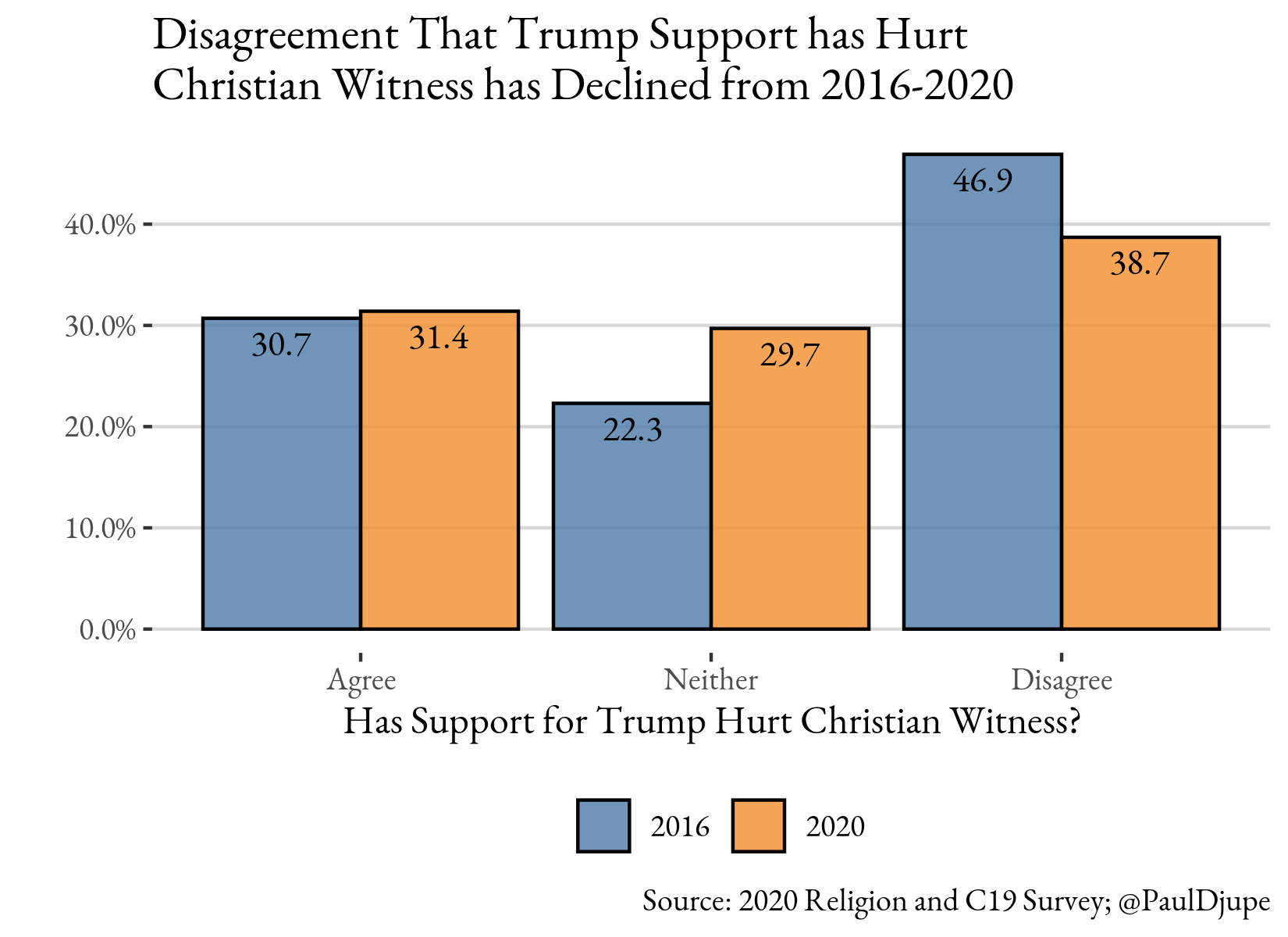

In several surveys now, I’ve asked if respondents agreed or disagreed that, “Christian support for Donald Trump has hurt Christian witness.” When Brian Calfano and I asked this in the week before the 2016 election, 47 percent of white Christians in our sample disagreed (note, the wording was slightly different – we asked whether “Public support for Donald Trump has hurt Christian witness”). When Ryan Burge and I asked it again in March 2020, disagreement had dropped to 39 percent. That does not mean that agreement has grown – it stayed the same at ~30 percent – but instead fence sitting has grown from 22 to 30 percent. Perhaps there is growing recognition that the association with Donald Trump is not doing any favors for white Christianity.

But this view isn’t widespread and the variation in holding it is revealing of some new fundamental truths about American religion. That is, American religion no longer seems to be guided by American religion. I’ll take the rest of the post to explain.

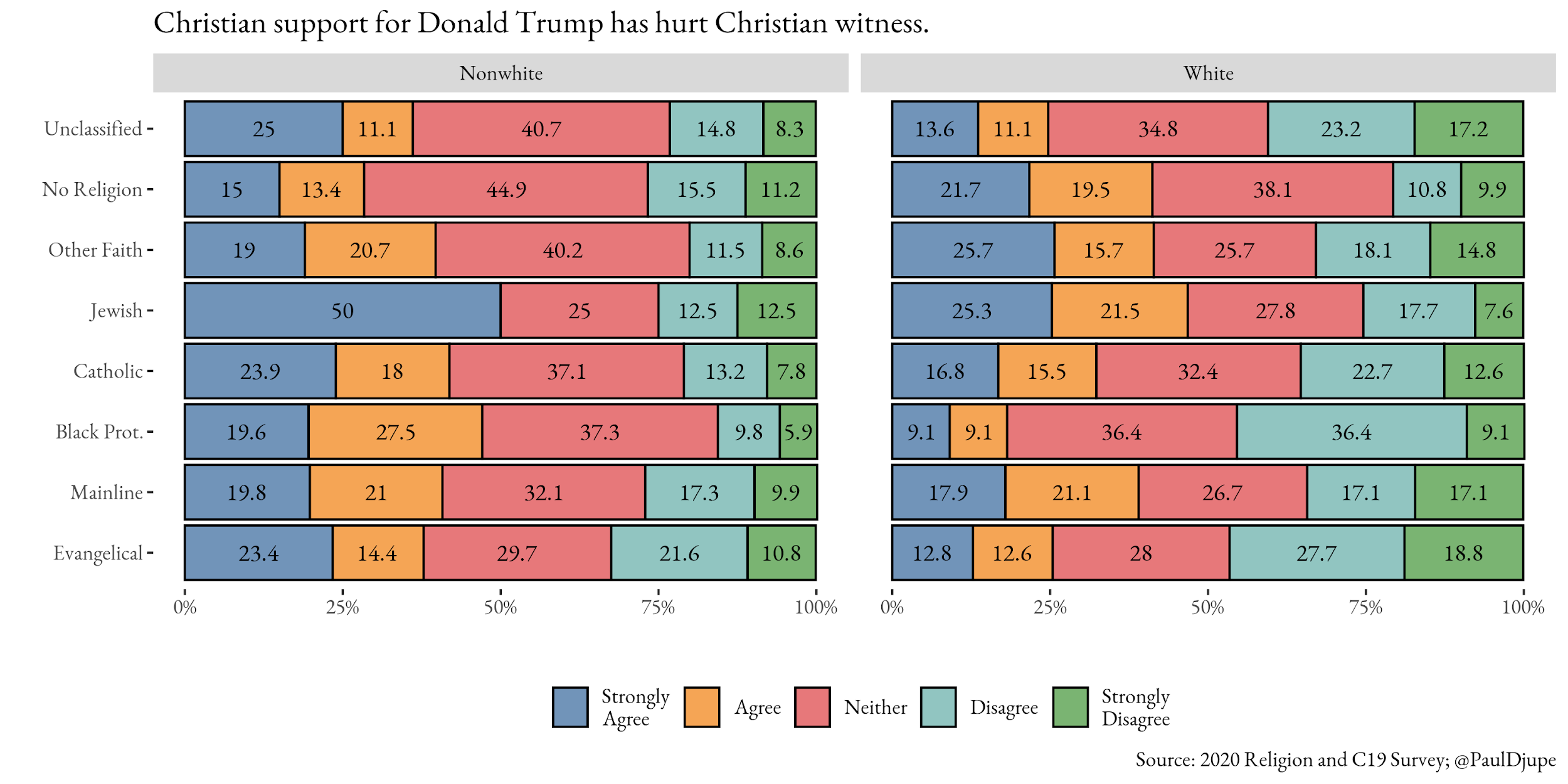

Let’s take a look at how views about Christian witness vary by religious tradition (and race). In the figure below, it is notable that nonwhites from each religious tradition are more likely to think that support for Trump has hurt Christian witness, but there is nothing close to unity in any group. Within racial groupings, evangelicals are more likely to disagree with this statement, but it is not a majority view (close though). The consistently largest single response category is neither.

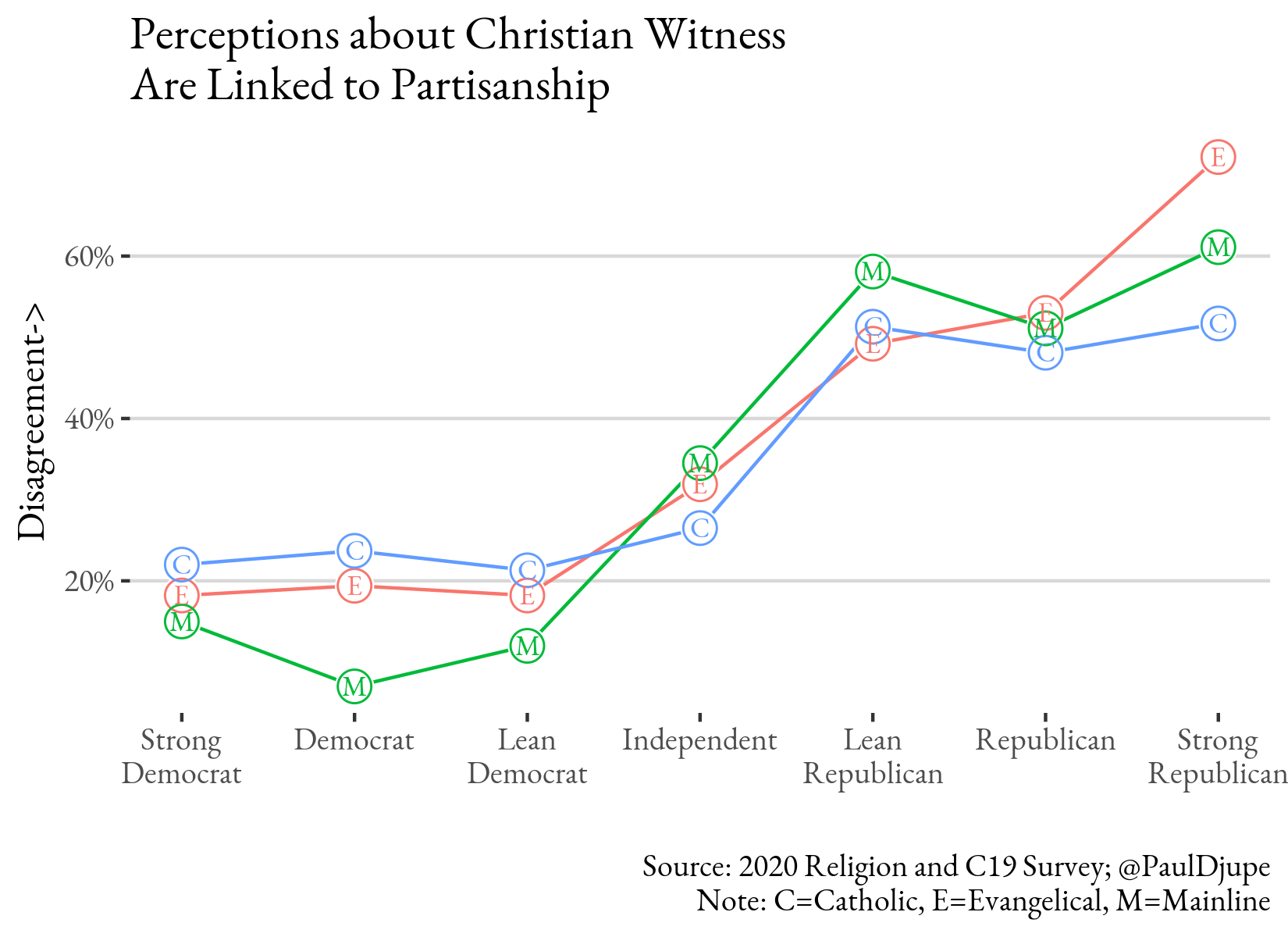

This is not a statement about how the individual feels, but rather asks for their perceptions about how effective Christian evangelizing can be when Christianity is tied to Donald Trump. It pays to think about this as a market transaction. Many Christians now represent a product that is tied to Trump and its success might therefore hinge on demand for “Republican religion.” Some of that is bound to be personal as the following figure shows. There is a strong shift in views along with partisanship. That is, the most agreement that Trump support has hurt Christian witness comes from strong Democrats, whereas the most disagreement comes from strong evangelical Republicans. And by and large this pattern does not shift by religious tradition. Partisan Mainliners have essentially the same views as partisan Catholics and evangelicals, though Catholics are a bit more agnostic on this question.

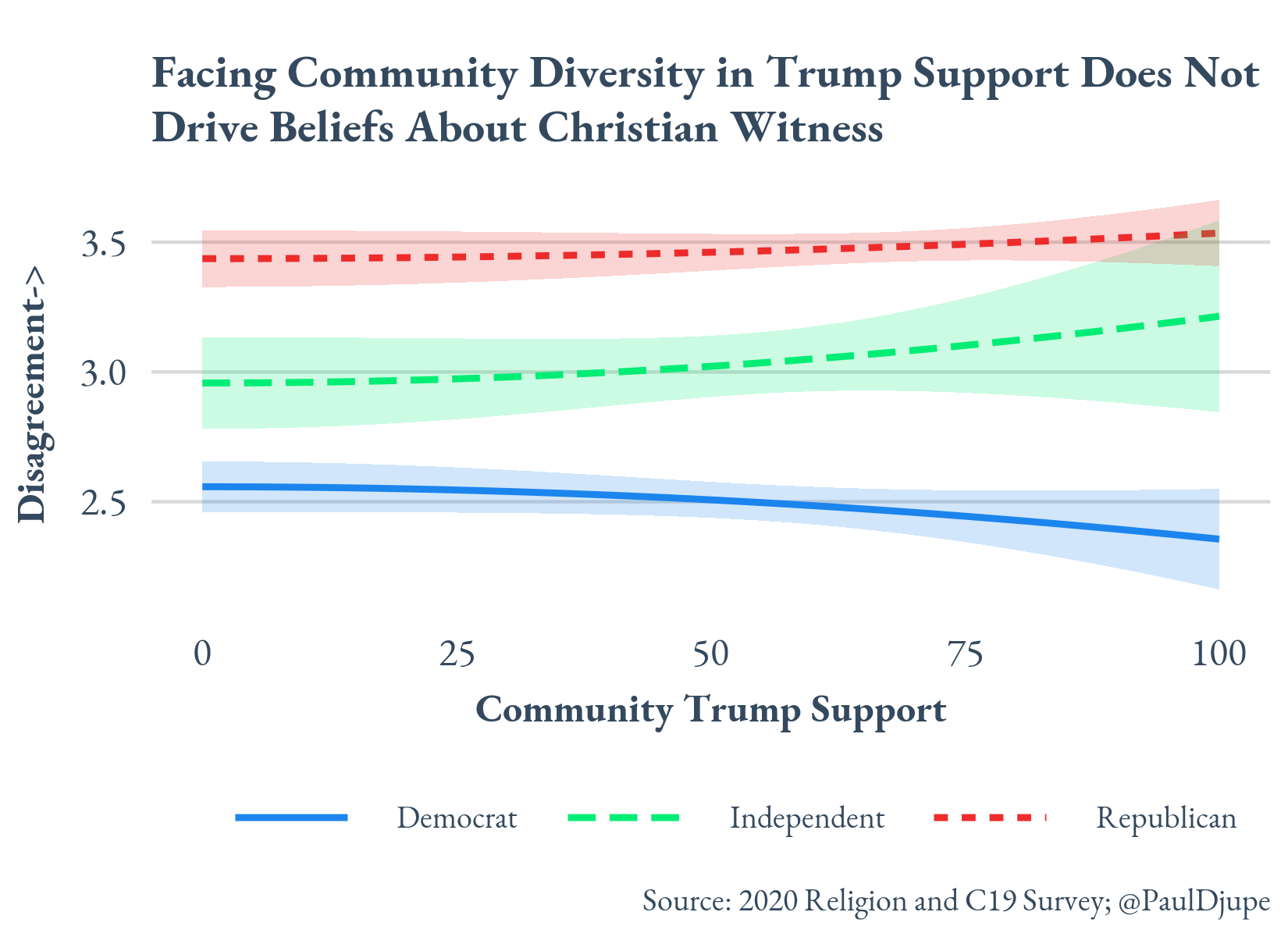

But, of course, partisanship is not just an individual identification, but a shortcut for thinking about many things, including the social context around them as people have increasingly sorted themselves into red and blue America. Therefore, we should expect that the partisan distribution in the community would affect thinking about the effectiveness of marketing Trump Christianity.

I’m particularly interested in how myopic this view is, so I’ll use two questions – one asking about the degree of Trump support among “my friends” as well as “my community.” Are views about Christian witness driven simply by their own partisan affiliation or do they update when surrounded by diverse views? Yes, there’s considerable variation on these questions, though Trump supporters/opponents tend to perceive living in Trump-supporting/opposing communities.

The following figure shows that perceived Trump support in the community has no bearing on how white Christians answered the Christian witness question. Republicans were consistently more likely to disagree that witness has been damaged, while Democrats were more likely to agree. And being surrounded by partisans of the other side does not matter a lick.

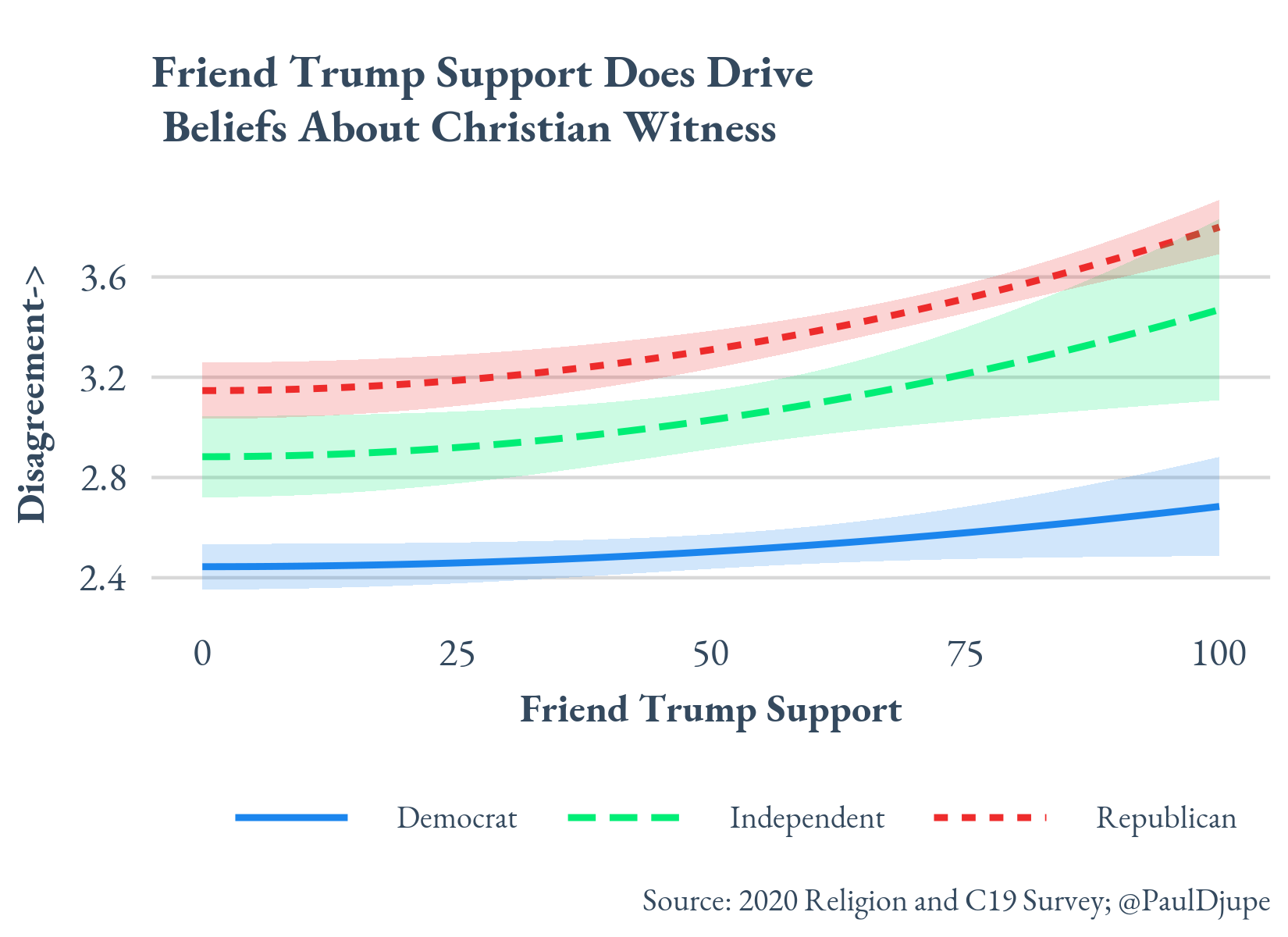

When we zoom in and ask about support for Trump among “my friends,” the picture changes. The partisan split is still there, of course, but the efficacy of Christian witness changes based on friendships. More Trump-supportive friends nudge the respondent to disagree that Christian witness has been affected. It’s especially strong for Republicans, but even Democrats show some movement in that direction. The opposite is true as well – perceiving opposition to Trump among friends leads to greater agreement that Christian witness has been damaged. Opposition to Trump among their friends puts Republicans on the fence.

Admittedly, this is a difficult question for people to answer. The ‘truth’ has not yet been uncovered by social scientists, though there are suggestive results that disagreement over Trump did lead people to leave their congregations. So, people search for clues around them and use their own dispositions as a guide. The evidence suggests that friends are particularly important for gaining perspective on how the group may be perceived by wider society. If so, then the distribution of political friendship is critically important.

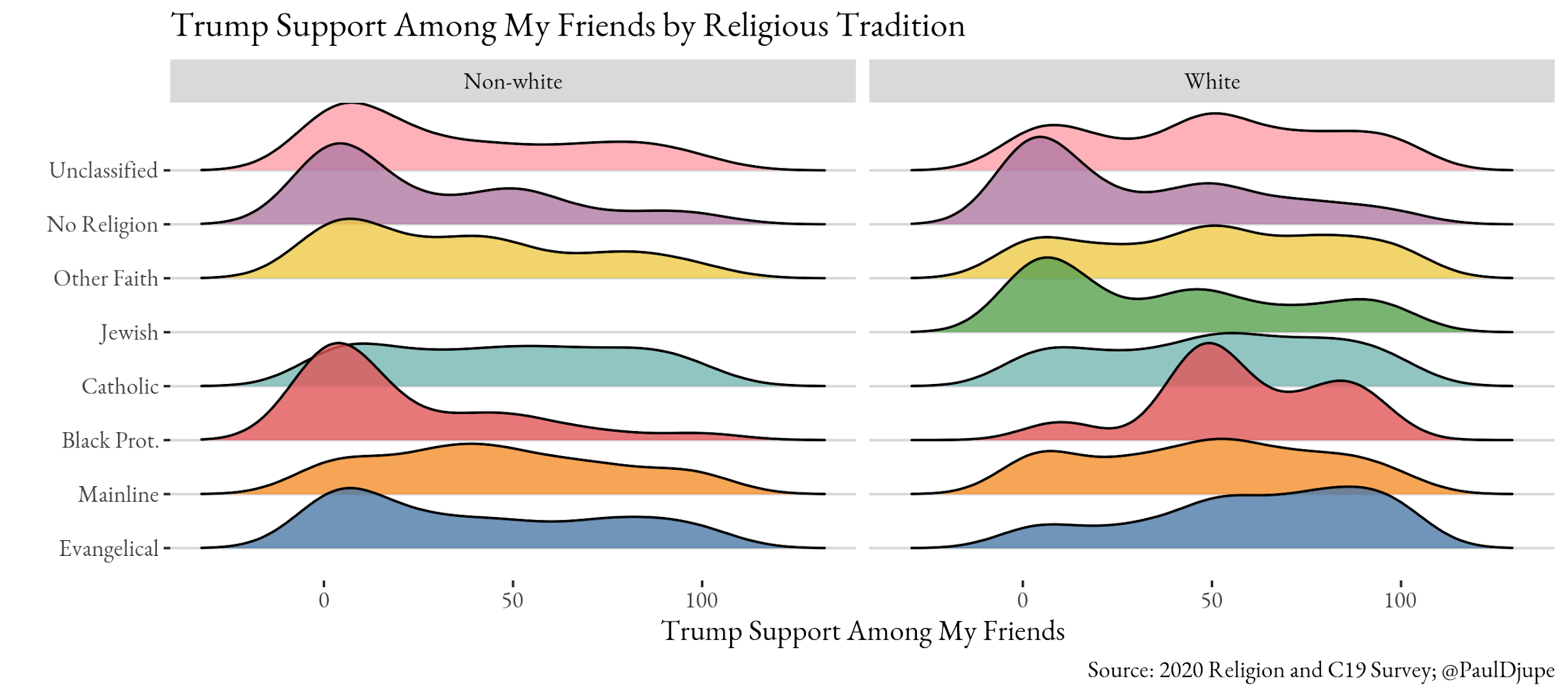

As the following figure shows, the distribution of Trump support among ‘my friends’ probably shows what you might expect it to. There are differences across religious traditions and especially by race. Evangelicals tend to perceive the most Trump support, but non-white evangelicals perceive quite a bit less among their friends. There’s considerable diversity among mainliners and Catholics. Only among the nones do we see unity by race – both perceive little Trump support among their friends. Regardless, these results help us see that, at this point, it is difficult, for instance, for evangelicals to see that the Christian brand has been damaged in society by its close association with Donald Trump. In part, that is because it has probably not been damaged among their bits of society.

One of the major findings of 21st century social science of religion is that the polarizing politics of the Christian Right appears to have driven people out of religion. The argument was pioneered by sociologists Hout and Fischer and reinforced through research by political scientists Stratos Patrikios, Michele Margolis, Jake Neiheisel, Anand Sokhey, Kim Conger and me. We’re starting to gain a good sense of the dynamics from this work, that it relies on salience and personal exposure, that it is more likely when identities are fluid, that weak ties with a religious group facilitate movement. Here we see that growing social sorting, which is still far from perfect, helps to insulate people from seeing the consequences of politicizing religion. It would take a massive, coordinated effort from religious elites to break through these bubbles. That could happen in the Catholic Church, but there is no mechanism for that to happen within heavily decentralized evangelicalism, which not coincidentally is the religious group most affected by these dynamics.

Look for the forthcoming book in the Religious Engagement in Democrat Politics series from Felipe Mantilla to make this argument in great detail.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the book series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

[…] also makes sense given the structure of the religious group – it is highly decentralized with clergy entrepreneurs looking to attract people from a particular community. The rise of highly localized, non-denominational Christianity […]

LikeLike