Paul A. Djupe, Denison University

I generally like David French’s commentary. We don’t share the same religion, but I suspect we share many of the same (democratic) values and, generally, I just think he’s a thoughtful guy. When academics start by saying they like someone, it’s probably a good signal that they’re about to go after that person’s argument. And that’s true here, to a point.

In his latest piece for the New York Times, he describes the “Rage and Joy of Donald Trump’s MAGA America.” It’s a neat argument, backed by his personal observations while immersed in the South, that MAGA supporters are not just angry about the state of the world and the leftist/globalist/whatevers they believe are wrongly in charge. They are actually pretty happy in the MAGA communities they’ve inhabited in the traveling circus following Trump around the country and in their local communities. The importance of that observation is this: they will need a replacement for that communal joy to encourage them to sever their connection to MAGA, not just steps that would defuse their anger.

That’s all fine with me in the sense that it’s worth studying more systematically to see if there’s something to it.

What I’m concerned with is his extension to religion and especially evangelicalism. The parallel he draws is this: “Evangelicals are a particularly illustrative case. About half of self-identified evangelicals now attend church monthly or less often. They have religious zeal, but they lack religious community. So they find their band of brothers and sisters in the Trump movement.” I’ve heard this sort of argument A LOT in the Trump years, trying to make the argument that church-involved people are the good, well-behaved ones who wouldn’t support Trump, while the non-attenders who still identify as religious/evangelical/whatever are the ones doing the objectionable thing in the news at the moment. The implication is that if those MAGA types could just get back to church (or in some other community), then the MAGA problem would be solved.

I’ve addressed this several times before in several different ways and I’m surely missing some posts, but let me say it again: church attendance is linked to Trump support. Let’s go through some more recent evidence from 2020-2023.

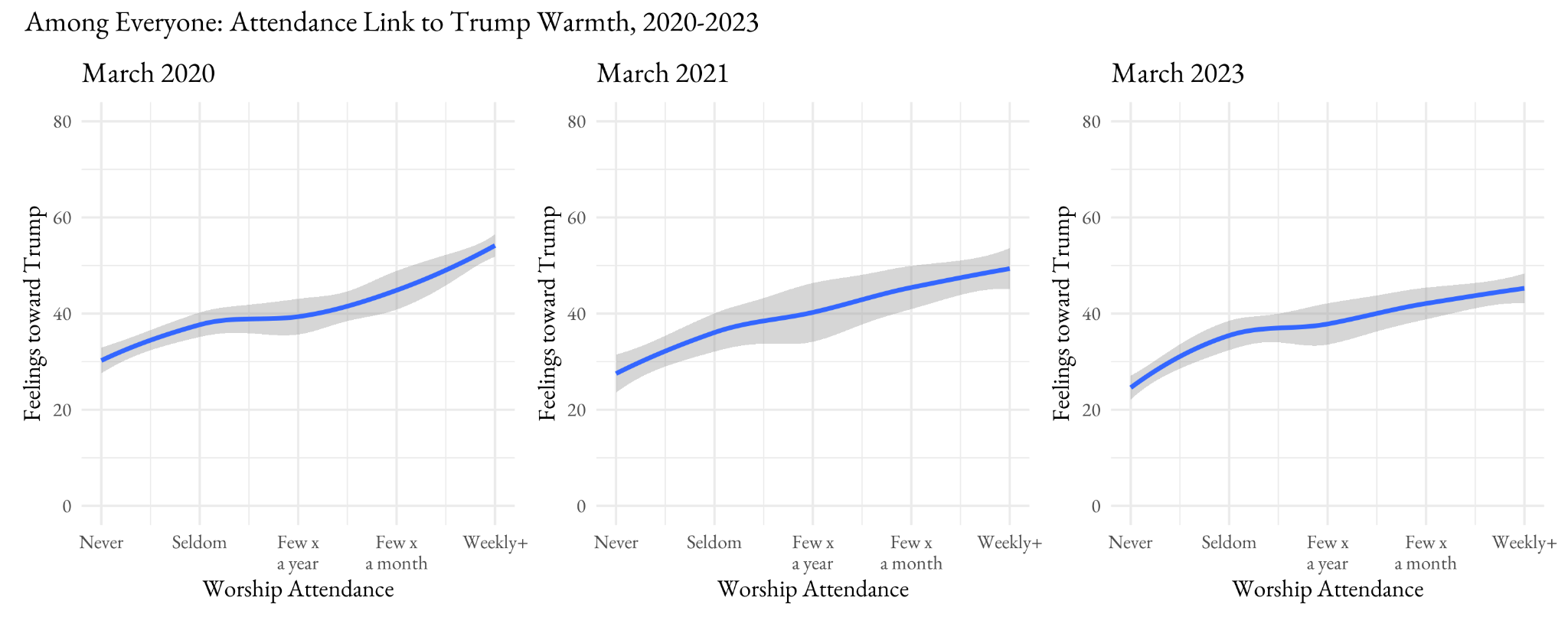

I’m looking at three surveys I administered with colleagues of American adults in March 2020, 2021, and 2023 (all data are weighted). I’m starting with just attendance in the entire sample. I expect that the non-attenders won’t feel very warm toward Trump (using a ‘feeling thermometer’ with scores ranging from 0/cold to 100/warm). And the attenders are a more diverse lot from varying religions, so perhaps they don’t show strong Trump support in these years.

The figure below shows that the link between worship attendance and warmth toward Trump is positive and modestly strong. Warmth increases by about 20 points on the scale across levels of attendance in each survey, though one thing to note is that warmth toward Trump has dipped a bit – it is off by about 5 points in 2023 compared to 2020. So far, no evidence for the argument French is making.

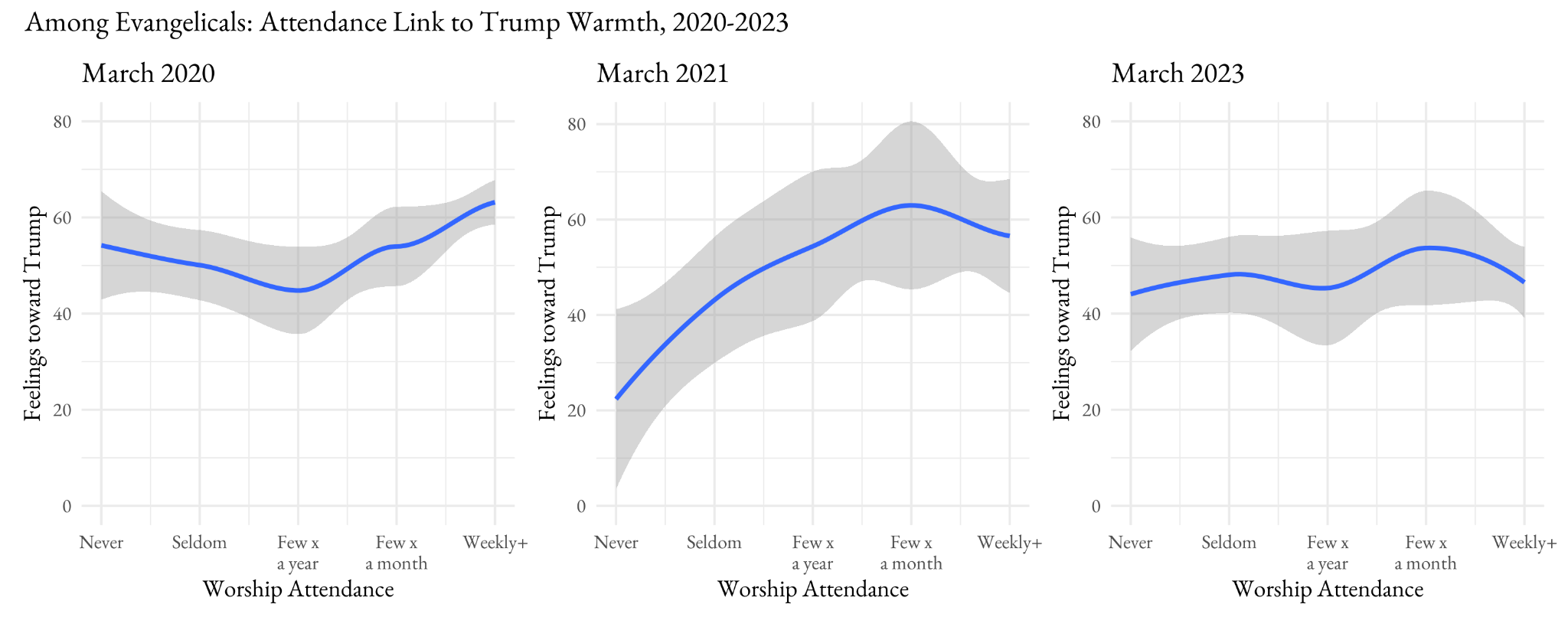

But he’s really just making the argument that evangelicals are divided based on whether they find community in churches or among “the battle and the booze cruise.” So, let’s look just among denominationally identified evangelicals (I checked to see if using evangelical self-identification makes a difference and it doesn’t – the results look about the same). Here attendance doesn’t really make a difference. In March 2020 and 2023, there is barely any movement across the attendance scale and evangelicals feel, on balance, warmly toward Trump. The exception is March 2021, where non-attenders fell off the wagon briefly. By March 2023, they were back on board. Careful observers will note a bit of a fall-off among frequent attenders who were just above 60 in their warmth toward Trump in 2020, but were just below 50 in March 2023. All that means is that by 2023 they are unexceptional in their warmth toward Trump, not distinguishably higher as they had been before. Again, there is no evidence that non-attending evangelicals are a bastion of MAGA support compared to those who are involved in evangelical churches.

My hunch is that French is hearing from people who occupy a very particular slice of evangelicalism. From the look of the data above, those bothered by the MAGA association with evangelicals are interspersed throughout attendance levels so we can’t see obvious evidence of them, but they certainly exist.

What I think French and many others are missing is that church involvement is not the crucial dividing line here, but instead the kind of religious beliefs that the people hold are. This is a particular blindspot among some scholars of religion who think of American society as divided between church attenders versus those who are not. Of course there’s some of that, but if you really want to understand who is MAGA and who isn’t, you need to be thinking about apocalypticism. The people fixated on dividing the world into the forces of good and evil (demonic, embodied evil), see Christians facing rampant persecution, and foresee (yep, prophecy belief is a big part of this) a final battle ahead are on a different plane of existence from other people. And they certainly do feel warmly toward Donald Trump, anointed to be their savior.

The following figure only includes evangelicals, which is why there is essentially no one who has zero apocalypticism. In contrast to the figure above where attendance levels resulted in zero difference in feelings toward Trump among evangelicals, apocalypticism shows enormous differences. Those on the high end of the scale average over 80 (feeling quite warmly toward Trump), while those on the low end (about .25 among evangelicals) average between 0-20 (quite cold) in the two surveys where I have these measures (March 2021 and 2023). That’s almost the entire range of the feeling thermometer scale.

David French laid out a thoughtful approach to thinking about how to deradicalize MAGA folks, but he’s wrong in his assumptions about the role of religion here. Among some, church involvement as it shows through apocalyptic beliefs is an accelerant of MAGA, not a replacement for it. The dividing line is clear. Those with religious beliefs that draw sharp lines between good and evil and feature elites who are making the case that Trump is the anointed ruler of America (and whose indictments are demonic) are the most dangerous and powerful support structures of the MAGA movement. We need to stop thinking that religion is the antidote – particular forms of it, like the New Apostolic Reformation, may be the cause of the problem.

Professor Paul A. Djupe directs the Data for Political Research program at Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog. Further information about his work can be found on his website and on Twitter and Threads.