By Paul A. Djupe

[Note: image credit to Salon.com]

A common response to some of our recent posts about the distinctiveness of evangelical politics is to duck and cover. That is, for some, the extreme stances are not a result of religion per se, but of being white and conservative. Others are not convinced that these are “real” evangelicals, but some enormous band of impostors. For the life of me I can’t figure out why these people would want to pretend that they are evangelical without reality behind it – what cultural cache is there in this identity today? Anyway, these are reasonable hypotheses and it’s surely worth going through them yet again.

Here’s my tack: I’m going to the well of the 2018 Cooperative Congressional Election Study, in part because it’s recent, but also because the enormous sample size of 60,000 enables precise looks at small groups. They asked a group of support/oppose questions regarding recent policy proposals that can be attributed to Trump and the Republican Party more generally. Assessing how these cluster by religious group is an important first step, but then I will show how support changes with worship attendance. If there are impostors (aka cultural identifiers), surely some variation will emerge compared to “true believers.” Are the cultural identifiers the ones taking the extreme stands with Trump?

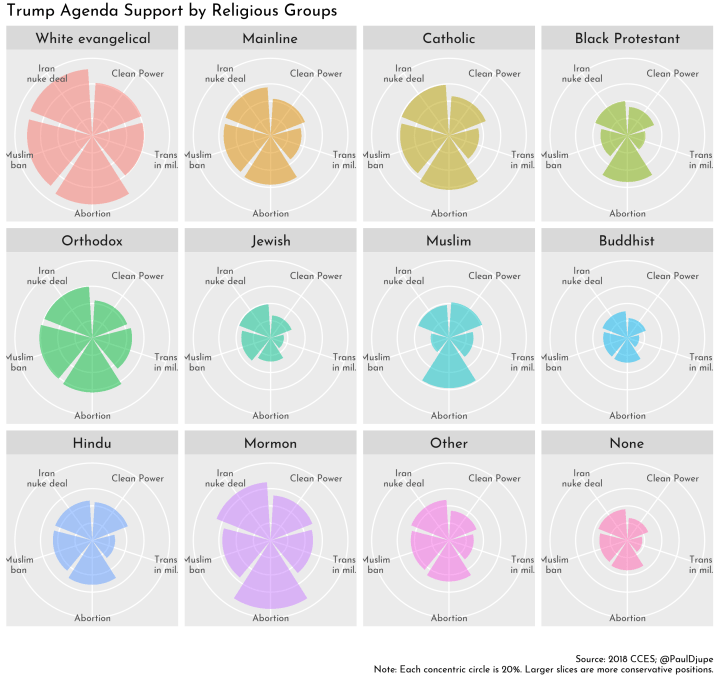

Here are the issues I included (questions CC18_417_a through CC18_417_d as well as the abortion question CC18_414E). In May 2018 Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed harsh sanctions on the country against the advice of American allies. The survey statement said just that, “Withdraw US from the Iran Nuclear Accord and reimpose sanctions on Iran.” From the get go in early 2017, Trump imposed, in his words, a Muslim ban, which was subsequently altered after judicial proceedings. The survey question read, “Ban immigrants from Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, Syria and Libya from coming to the United States for 90 days. Permanently prohibits Syrian refugees from entering the country.” Another action taken was to ban transgender people from serving in the armed forces, which took effect in April 2019. The Trump Administration also worked to end the Clean Power Plan, which required states to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 32 percent of 2005 levels by 2030, repealing them as of June 2019. I also included a question about a ban on public funding for abortion. In each case below, the larger the slice, the more conservative the policy position. By the way, Protestants are distinguished by race and denominational affiliation, not just identity.

By and large these groups are consistent ideologically – support for these policies rise and fall together. However, there are a few surprises in there. Black Protestants and Muslims show stronger opposition to abortion compared to their support for the other policies. Most all groups show less, even much less, support for the ban on transgender people in the armed services, but it is essentially nonexistent among small religious minorities such as Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists. Jews show more support for pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal. Mormons show support as conservatives would but some are clearly uncomfortable with Trump’s agenda.

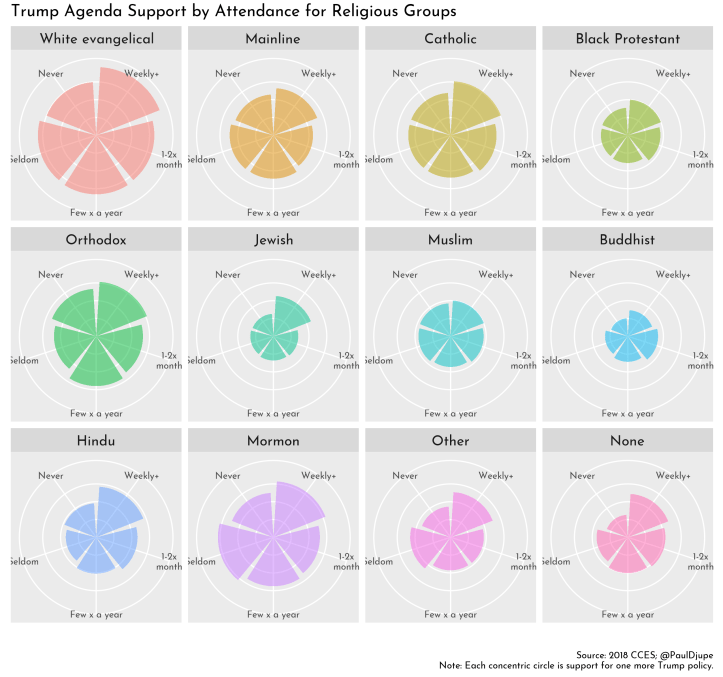

But that’s not why we’re here. Instead, we need to know if support for Trump’s agenda shifts by their level of commitment to the faith tradition. There are many ways to measure that, but the stalwart is worship attendance. In this case, I’ll show the mean level of support for the five Trump/Republican policies by attendance level for each religious group.

There is a notable bump within almost every religious group for weekly (or more often) attenders – weekly attenders support Trump’s agenda more than any other level of attendance within the religious group. That level of support is relative, however. Support among white evangelical weekly attenders is much higher than support among Catholic weekly attenders, which is greater than mainline weekly attender support, and so on. But let’s pause a moment to reflect that, again, the most observant white evangelical Protestants are the most committed to Trump’s agenda. Other evangelicals favor Trump’s agenda at high rates, but there is no evidence to suggest that “true” evangelicals are actually holding Trump at arm’s length.

Quick Detour :: There are some other interesting nuggets here that you may have noticed. There is essentially no variation by attendance among Muslims, and little among Buddhists and Black Protestants. This is a sign of social pressure on the group that works to unify it. Were that pressure removed, we might see expanded diversity of opinion emerge. Jews show no diversity in opinion by attendance except for the weekly+ category, which reflects the high concentration of Orthodox Jews there. This is true of other groups as well – there is substantial religious variation within these broad categories.

Still not convinced that American religion is often a conduit for conservative politics? It is true that ideology is strongly correlated with support for Trump’s policy agenda, even though his stances sometimes upend the traditional formulation (like trade). Even controlling for ideology in a model, people are mostly distinguishable given their religious group and attendance level as the following figure shows. White evangelicals who attend weekly+ are more supportive of Trump’s policies, though not tremendously so, and overall evangelicals have the highest level of support for Trump’s policies. There certainly is no evidence to support the opposite – that true evangelicals support Trump less.

There is no effect of attendance among mainliners, which may attest to the diversity within the religious group. Catholics, Jews, Hindus, and nones all show the expected relationship – more attendance is linked to greater support for Trump’s policies. Muslims and Mormons stand out for the reverse relationship – more observant members of both groups support fewer of Trump’s policies.

I have no doubt that political forces, especially partisanship, has overwhelmed religious groups and their influence at this point. I would (and have) called this a crisis of religious authority and still argue that greater independence of religious groups is important for a thriving democracy. That is not what the evidence suggests at this point. Instead, most majoritarian religious groups are conduits through which partisan ties are cemented, not weakened, which suggests to me that religious leaders are frankly too risk averse to chance a major loss of members in a struggling religious economy. Instead, if they address political issues and figures, it tends to reinforce partisan ties.

Paul A. Djupe, Denison University, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (check out his posts). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.